Former colored entrance to a theater, Kilgore (TX).

The six faded letters are all that remain, and few people notice them. I would never have seen them if a friend hadn’t pointed them out to me while we walked through New Orleans’s French Quarter. I certainly wouldn’t have realized their significance.

On Chartres Street, above a beautifully arched doorway, is a curious and enigmatic inscription: “CHANGE.” Now part of the facade of the Omni Royal Orleans Hotel, the letters mark the onetime site of the St. Louis Hotel & Exchange, where, under the building’s famed rotunda, enslaved people were once sold.

Several years ago, I began to photographically document vestiges of racism, oppression and segregation in America’s built and natural environments — lingering traces that were hidden in plain sight behind a veil of banality.

When the Omni Royal Orleans (left) was built in the 1950s, some of its history was incorporated into a small section of the building. The word “change” is a fragment salvaged from the original St. Louis Hotel and Exchange. The remaining letters were lost.

Some of the sites I found were unmarked, overlooked and largely forgotten: bricked-over “Colored” entrances to movie theaters, or walls built inside restaurants to separate nonwhite customers. Other photographs capture the Black institutions that arose in response to racial segregation: a Negro league stadium in Michigan, a hotel for Black travelers in Mississippi. And a handful of the photographs depict the sites where Black people were attacked, killed or abducted — some marked and widely known, some not.

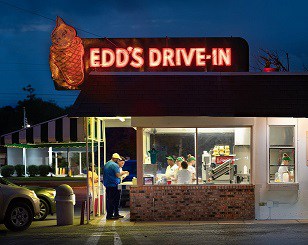

The small side window at Edd’s Drive-In, for example, a restaurant in Pascagoula, Miss., appears to be a drive-up. It was actually a segregated window used in the Jim Crow-era to serve Black customers.

The locked black double doors aside Seattle’s Moore Theatre (below) might be mistaken for a service entrance. In fact, this was once the “Colored” entrance used by nonwhite moviegoers to access the theater’s second balcony.

These sites surround us, but finding and verifying them requires months of due diligence.

The very existence of the door shocked me. I had walked past it countless times over the 40 years I’ve lived in Seattle, never giving it a thought. It wasn’t until the summer of 2020 that the tragic nature of this obscure door resonated with the sobering reminder on the marquee.

Former colored entrance at Seattle’s Moore Theatre

After being tipped off by a contributor to a website called Preservation in Mississippi, I verified the history of the window at Edd’s Drive-In with the manager, Becky Hasty, who told me that the owners had retained it as a reminder of the past. “If we don’t remember where we’ve been,” she said, “we might get lost again.”

Next week: Part 2 – The Original Sin

Rich Frishman’s photography is in a wide range of private and institutional collections in the US. His work has garnered dozens of prestigious awards. In 1983, he was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize. He lectures around the US about the intersection of the designed environment, history and social issues. Click here for his website. All pictures © Richard Frishman. This blog series is an adaption of on an article by Richard Frishman previously published in the New York Times. Edited by Mieke Bleeker.

Rich Frishman’s photography is in a wide range of private and institutional collections in the US. His work has garnered dozens of prestigious awards. In 1983, he was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize. He lectures around the US about the intersection of the designed environment, history and social issues. Click here for his website. All pictures © Richard Frishman. This blog series is an adaption of on an article by Richard Frishman previously published in the New York Times. Edited by Mieke Bleeker.