In my preceding essay, “The ‘Survivalist Interpretation’ of Slavery”–based on the findings of my book Disunion Among Ourselves: The Perilous Politics of the American Revolution–I lay out three paradigms for understanding why the founders of the United States did virtually nothing during the nine years of the American Revolution to put an end to the slave trade or slavery itself.

This inaction does not mean that awareness of the barbarity and despotism of slavery was not buried somewhere beneath the white supremacy, economic greed, and fears of disunion and civil wars. It was indeed, and although scant records exist today of a public abolitionist spirit among the founders in the first decades of the nation, there are exceptions to the rule.

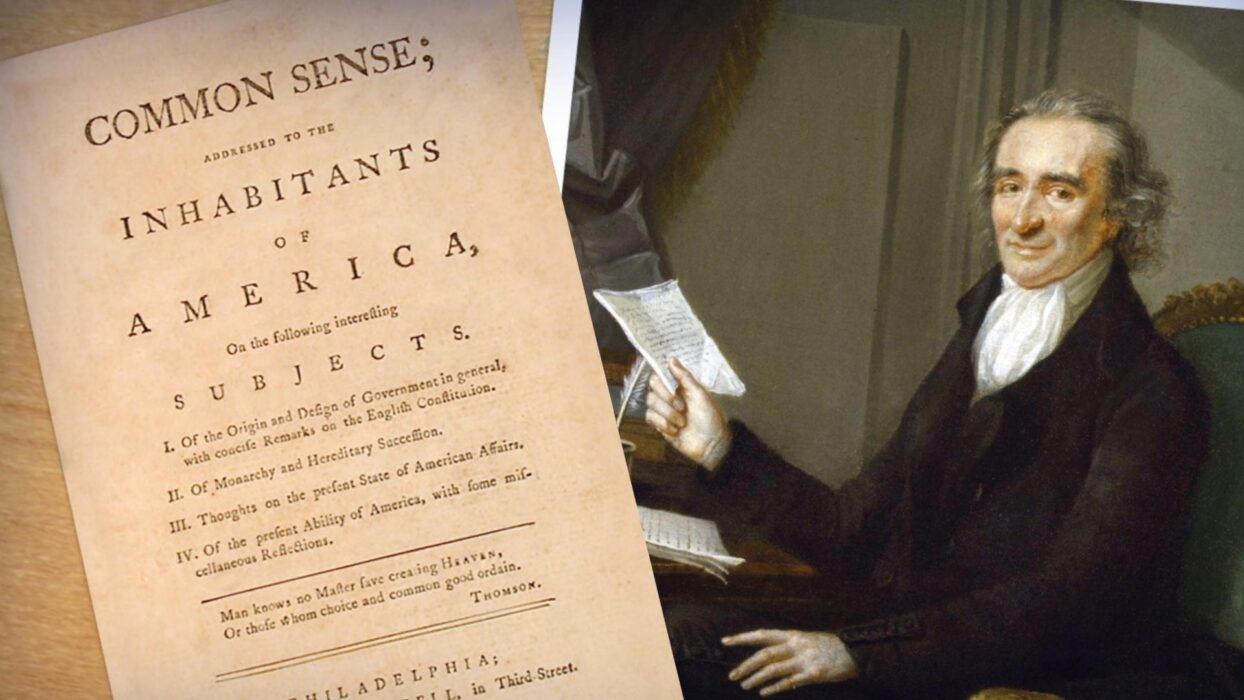

One such notable example comes from the pen of Thomas Paine, future author of the political manifesto Common Sense. In the spring of 1775 Paine, thirty-seven years old, charismatic, and possessing one of the most progressive Enlightenment minds of the 18th century, published the abolitionist tract, “African Slavery in America.”

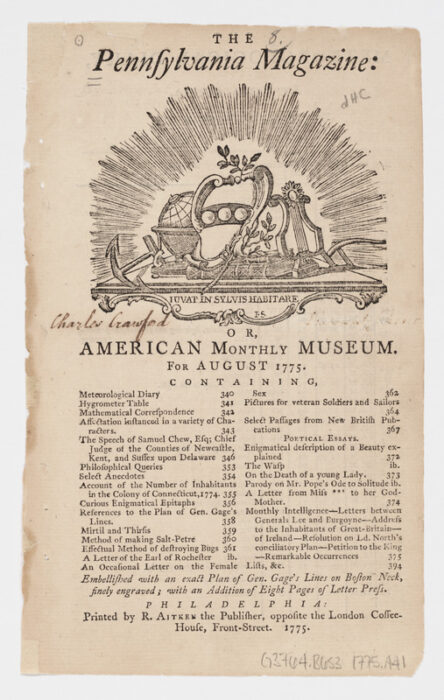

The Pennsylvania Magazine or, American Monthly Museum (Aug. 1775)

Paine had only arrived in America from London five months earlier, and by good fortune, while browsing at a Philadelphia bookstore, he met its owner, Robert Aitken. The bookseller was also a printer with imminent plans to launch a magazine called The Pennsylvania Magazine; or American Monthly Museum. In search of work, Paine showed Aitken several unpublished manuscripts, and soon the Philadelphian, impressed by the newcomer’s intellect and facile pen, hired Paine as a writer and editor.

Aitken declared publicly to the readers of the magazine that its editors were intent upon a stance of neutrality on volatile subjects. But this was not the nature of Thomas Paine. Trim, five feet eight inches in height, dark hair pulled back into a queue, Paine was instead a liberal crusader whose tendency was always to advance the banner of human progress.

By the time of the Battle Bunker Hill (1775), Paine wished ardently not only for American independence from vice-ridden Britain for white Americans but also for education and civil rights for women and the emancipation of enslaved people. So moved was he by the plight of American enslaved persons—and the institution’s gross incompatibility with the liberty Americans espoused—that he penned a paper on the subject months before he wrote Common Sense.

Aitken, it seems, refused to publish Paine’s first provocative treatise on an urgent American political and moral theme. So Paine tendered it to The Pennsylvania Journal and the Weekly Advertiser, where it appeared on March 8, 1775, under the nom de plume “Justice and Humanity.” In the article, African Slavery in America, Paine begins by deploring slave traders, calling out the hypocrisy of a Christian citizenry tolerating such a vile criminal practice.

“That some desperate wretches should be willing to steal and enslave men by violence and murder for gain,” he writes, “is rather lamentable than strange. But that many civilized, nay, christianized people should approve and be concerned in the savage practice is surprising; and still persist, though it has been so often proved contrary to the light of nature, to every principle of Justice and Humanity.”

Above all, Paine condemns the slave trade in the essay, but he also outlines pathways to emancipation in the here and now. One pressing question of the day, Paine says, is, “What should be done with those who are enslaved already? To turn the old and infirm free would be injustice and cruelty; they who enjoyed the labours of their better days should keep and treat them humanely.”

However, he continues, slavery should be terminated, and formerly enslaved people should be protected in their freedom legislatively by grants of land and economic opportunity as well as by guarantees that “the family may live together”:

As to the rest, let prudent men, with the assistance of legislatures, determine what is practicable for masters, and best for them. Perhaps some could give them lands upon reasonable rent, some, employing them in their labour still, might give them some reasonable allowances for it; so as all may have some property, and fruits of their labours at their own disposal, and be encouraged to industry; the family may live together, and enjoy the natural satisfaction of exercising relative affections and duties, with civil protection, and other advantages, like fellow men.

As a testament to the culture of white supremacy, greed, and acute fears that any attempt to end the slave trade or slavery in the 1770s and 1780s would spark disunion and civil wars, Paine’s 1,600-word soaring condemnation of slavery met with little fanfare in the colonies. In fact, The Pennsylvania Journal and the Weekly Advertiser ran it as a postscript at the end of the paper. As far as is known, no other colonial newspaper reproduced it.

In contrast, Paine’s next political tract, Common Sense, released in January of 1776, was published and republished so many times that by April more than one hundred thousand copies were in circulation. It was the equivalent of a runaway bestseller in modern times, and its success was race-based, celebrating white political emancipation from the British empire while grossly ignoring Black slavery, one of the worst crimes against humanity ever committed in world history.

Eli Merritt is a political historian at Vanderbilt University who specializes in the founding era of the United States, the ethics of democracy, and the intersection of demagogues and democracy. He is the author of ‘Disunion Among Ourselves: The Perilous Politics of the American Revolution’. He is also the editor of ‘The Curse of Demagogues: Lessons Learned from the Presidency of Donald J. Trump’ and ‘How to Save Democracy: Inspiration and Advice from 95 World Leaders‘. His articles have appeared in the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, and Chicago Tribune, among other outlets, and he writes American Commonwealth, a Substack newsletter that explores the origins of the United States’ political discontents and solutions to them. Sign up for American Commonwealth.

Eli Merritt is a political historian at Vanderbilt University who specializes in the founding era of the United States, the ethics of democracy, and the intersection of demagogues and democracy. He is the author of ‘Disunion Among Ourselves: The Perilous Politics of the American Revolution’. He is also the editor of ‘The Curse of Demagogues: Lessons Learned from the Presidency of Donald J. Trump’ and ‘How to Save Democracy: Inspiration and Advice from 95 World Leaders‘. His articles have appeared in the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, and Chicago Tribune, among other outlets, and he writes American Commonwealth, a Substack newsletter that explores the origins of the United States’ political discontents and solutions to them. Sign up for American Commonwealth.

This was the last part of this blog series.