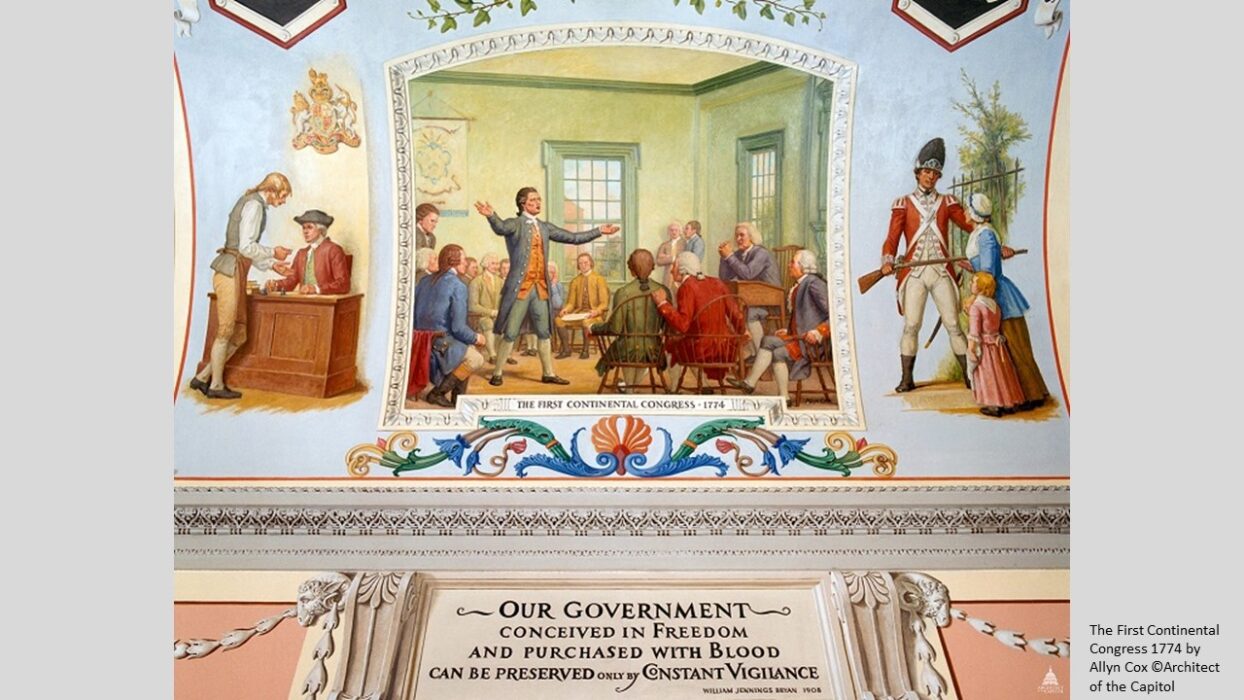

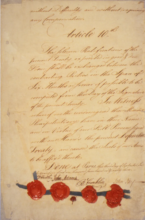

My book Disunion Among Ourselves: The Perilous Politics of the American Revolution tells the story of regional conflict and disunionist crisis in the Continental Congress from 1774, when delegates from the colonies first gathered to protest the deplorable Intolerable Acts, until 1783, when the Treaty of Paris finally secured independence and ended the war.

Treaty of Paris (1783)

What surprised me most in my research––until, finally, I penetrated the depth of fear in the psyches of the founders that a wrong move in Congress might spark disunion and resultant self-destruction in civil wars––is the virtual absence of political discord and agitation about slavery during those years.

How do we explain the unconscionable barbarism, horror, and savagery perpetuated by these supposedly brilliant Enlightenment thinkers who celebrated liberty and equality more than any other values on earth? In the book, I propose three explanatory models that account for the founders’ silence and inaction on one of the greatest crimes against humanity ever committed in world history.

Two of the models are well-known: the white supremacist and the economic interpretive lenses. By the former, the founders’ failure to enact some federal plan of emancipation was rooted in systemic racism and moral corruption, underpinned by perverse readings of the Bible.

The latter interpretation lays blame on the entrenched economic systems in both the North and South that enriched white planters and merchants on the profits of the slave trade and slave labor. No matter how heinous these practices were, the economic argument emphasizes, the founders simply could not break their addiction to the lucrative status quo.

These two explanatory models are correct, but they overlook an additional, less-known factor that weighed heavily on the minds of the founders: the belief that any attempt by the federal government to end slavery or the slave trade would tear apart the United States.

George Washington at Mt. Vernon and enslaved people (painting by Junius Brutus Stearns)

One significant reason for the founders’ inaction on slavery on the federal level is their fear of disunion and civil wars. Antislavery advocates, like John Adams, John Jay, Alexander Hamilton, James Wilson, and Benjamin Franklin, among others, did not dare attempt to mandate even the gradual emancipation of enslaved persons throughout the thirteen states because they were certain that such a move would inflame divisions and disunion between North and South at the very moment they were working so hard to unite the fractious states into one Union—in order, for one thing, to prevent civil wars in the first place.

Because the founders of the United States believed that some, if not all, of the Southern states would secede from the Union if the Northern states demanded a plan of emancipation or an end to the slave trade—and because any such secession would drive the states into bloody mayhem— they faced a stark choice in the 1770s and 1780s.

They could either advance a federal program for liberating Black Americans from slavery or they could secure freedom from civil wars for themselves. They chose the latter, white self-preservation, making a grievous devil’s bargain.

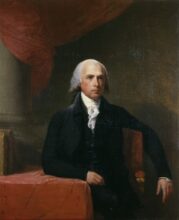

James Madison, by Gilbert Stuart

As James Madison explained the decision-making of the Constitutional Convention, referring to the slave trade: “Great as the evil is, a dismemberment of the union would be worse.” What Madison meant is that any attempt to abolish the slave trade would rupture the Union of thirteen, disbanding the states into separate confederations that would make endless war upon one another.

All three of these interpretations––the white supremacist interpretation, the economic interpretation, and the survivalist interpretation––are historically accurate. Added together, they get us far closer to understanding why the founders perpetuated slavery than we have ever been before.

Not only this, embracing complex truth about why the founders’ perpetuated slavery––and any other aspect of history, for that matter––has great value to our democracy. The reason for this is that complex history is the most powerful medicine I know for maturing us as individuals and therefore for maturing us as a society. What happens if you only accept a single, simplistic interpretation of the causation of something as complex as why the founders perpetuated slavery? It narrows your mind. It makes you righteous and divisive, and it makes you a force for polarization, tribalism, culture wars, and history wars.

On the other hand, if we challenge our brains to accept that the white supremacist interpretation is correct and the economic interpretation is correct and the survivalist interpretation––that is, if we take a “Both/And” approach to learning and understanding, instead of an “Either/Or” approach––we grow emotionally and intellectually, and, in doing so, we help our democracy survive and thrive.

On the other hand, if we challenge our brains to accept that the white supremacist interpretation is correct and the economic interpretation is correct and the survivalist interpretation––that is, if we take a “Both/And” approach to learning and understanding, instead of an “Either/Or” approach––we grow emotionally and intellectually, and, in doing so, we help our democracy survive and thrive.

This dynamic, salutary effect of complex truth on our minds and on our democracy is one reason I love history so much. It’s also why I believe that we as a nation should teach history in grades K-college with the same priority, intensity, and vigor as reading, writing and arithmetic.

Eli Merritt is a political historian at Vanderbilt University who specializes in the founding era of the United States, the ethics of democracy, and the intersection of demagogues and democracy. He is the author of ‘Disunion Among Ourselves: The Perilous Politics of the American Revolution’. He is also the editor of ‘The Curse of Demagogues: Lessons Learned from the Presidency of Donald J. Trump’ and ‘How to Save Democracy: Inspiration and Advice from 95 World Leaders‘. His articles have appeared in the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, and Chicago Tribune, among other outlets, and he writes American Commonwealth, a Substack newsletter that explores the origins of the United States’ political discontents and solutions to them. Sign up for American Commonwealth.

Eli Merritt is a political historian at Vanderbilt University who specializes in the founding era of the United States, the ethics of democracy, and the intersection of demagogues and democracy. He is the author of ‘Disunion Among Ourselves: The Perilous Politics of the American Revolution’. He is also the editor of ‘The Curse of Demagogues: Lessons Learned from the Presidency of Donald J. Trump’ and ‘How to Save Democracy: Inspiration and Advice from 95 World Leaders‘. His articles have appeared in the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, and Chicago Tribune, among other outlets, and he writes American Commonwealth, a Substack newsletter that explores the origins of the United States’ political discontents and solutions to them. Sign up for American Commonwealth.