Despite being a rather sickly hypochondriac, James Madison outlasted all the other founders, living until June 1836, almost through Andrew Jackson’s second term as president. Through all that time he remained relatively confident in the superiority and durability of America’s constitutional order. He did occasionally harbor some real worries and experience some palpable disappointments, as might be expected, but these concerns were never so deep and lasting as to lead to disillusionment with the political system as a whole or to despondency about its future. In this, he was the proverbial exception that proves the rule among the founders.

James Madison

The obvious question is why Madison was such an outlier. Why did he remain largely optimistic about America’s constitutional order when so many of his compatriots came to despair for it?

One potential answer can be ruled out immediately. Given his familiar moniker “The Father of the Constitution,” one might assume that Madison was sanguine for so long because he got what he wanted out of the Philadelphia Convention and remained satisfied with the result, but this was by no means the case. In fact, Madison lost more battles than he won in Philadelphia, including a number of those that he regarded as most important, and at the Convention’s close he deemed the Constitution to be radically defective.

Yet Madison soon grew reconciled to the Constitution, and indeed became one of its biggest admirers, in a way that his coauthor of The Federalist, Alexander Hamilton, never quite did. And his confidence in America’s constitutional order endured, unbroken if not quite undisturbed, for almost another half century – not only through the 1790s, by the end of which Washington, Hamilton, and Adams had all grown disillusioned, and not only through Jefferson’s despondent final years, but also through much of the turbulent Jacksonian era.

Madison’s confidence can be attributed, at least in part, simply to his temperament. He was far more composed and even-tempered than the passionate Jefferson, the fiery Hamilton, the irascible Adams, or even Washington, whose pent-up anger occasionally burst through the stoic façade that he generally showed to the world. Madison’s unflappable disposition no doubt contributed to his lack of despair.

Tom Freeman’s painting of the burning of the White House by British troops during the War of 1812 during Madison’s presidency

On a related note, Madison also had lower expectations than the other founders regarding what was politically possible. He never supposed that his fellow citizens would consistently surmount partisanship or sacrifice their self-interest for the sake of the common good (as Washington and Adams, respectively, hoped they would), nor did he long for the nation to achieve economic and military greatness on the international stage or for virtuous yeoman farmers to conduct the politics of their local ward (as Hamilton and Jefferson, respectively, envisioned) – and this meant that he was less likely than the other founders to be disappointed in what America became.

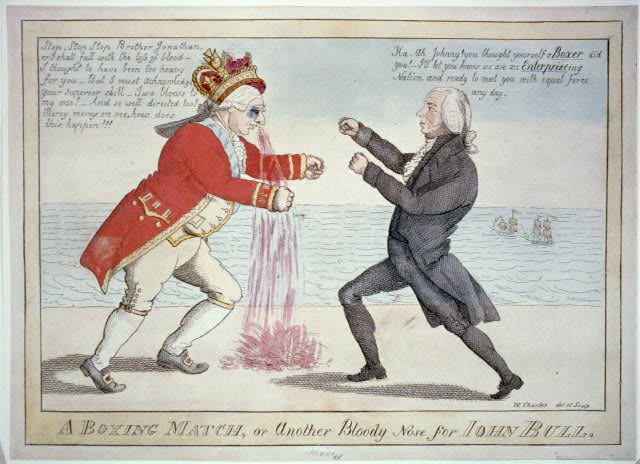

Still another explanation for Madison’s late-life confidence was precisely that by that point he had lived so long and seen so much in company with the nation that he had helped to found. He reasoned that if the Constitution and the union managed to survive the Alien and Sedition Acts (a harsh crackdown on civil liberties spurred by war hysteria), the War of 1812 (during which much of the capital went up in flames under Madison’s own watch), and the Missouri crisis (the biggest confrontation yet over the nation’s most divisive issue, the expansion of slavery), then surely they could survive a good deal more. The longer the nation endured, the more durable it seemed.

The War of 1812, depicted as a boxing match between King John III and James Madison

If Madison could find solace in the fact that America’s constitutional order had managed to weather nearly a half-century’s worth of storms by the time he reached old age, then perhaps we should be cheered to recall that it has now survived for more than two hundred and thirty years. This should not be taken as grounds for complacency, of course, for today’s political ills are both serious and pressing, as the elderly Washington, Hamilton, Adams, and Jefferson would surely remind us. Madison, though, would encourage us to summon a broader sense of perspective before announcing the doom of the republic.

Dennis C. Rasmussen is Professor of Political Science at Syracuse University’s Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs. He is the author of four books, including Fears of a Setting Sun: The Disillusionment of America’s Founders and The Infidel and the Professor: David Hume, Adam Smith, and the Friendship That Shaped Modern Thought, which was shortlisted for the Ralph Waldo Emerson Award. Click here for the first 5 parts of this blog series.

Dennis C. Rasmussen is Professor of Political Science at Syracuse University’s Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs. He is the author of four books, including Fears of a Setting Sun: The Disillusionment of America’s Founders and The Infidel and the Professor: David Hume, Adam Smith, and the Friendship That Shaped Modern Thought, which was shortlisted for the Ralph Waldo Emerson Award. Click here for the first 5 parts of this blog series.