Throughout his remarkable public career, one of George Washington’s foremost wishes for his country was that it would remain free of political parties and partisanship. All of America’s founders at least professed an aversion to “factions,” as they were frequently called, but none loathed them more fiercely, consistently, and sincerely than he did.

As Washington saw it, partisans are necessarily partial, meaning that they favor the interests of a parochial group over the public good. Partisans could not be true patriots. Parties were also, in his view, fatal to republican government. By sowing conflict, they divided the community and subverted public order; by opposing the government’s actions, they prevented its effective administration; by favoring some over others, they opened the door to political corruption and foreign influence.

In the event, of course, America’s first party system, which pitted the Federalists against the Republicans, emerged within the first few years after the Constitution was ratified and the new government was set up. In fact, the two sides were led by a pair of bitter enemies within President Washington’s own Cabinet, Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton and Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson.

By 1792, the year in which he reluctantly accepted a second term as president, Washington had already begun to bemoan the “internal dissentions” that were “harrowing & tearing our vitals” and making it “difficult, if not impracticable, to manage the Reins of Government or to keep the parts of it together.” Unless the partisan bickering abated, he warned Jefferson, the republic “must, inevitably, be torn asunder.”

When the partisanship did not abate — on the contrary, it grew continually worse over the course of his second term — Washington’s outlook became ever more bleak. He immortalized his worries for posterity in his famous Farewell Address of 1796, the great theme of which was the dangers of factionalism in its various guises: political parties, geographic divisions, and the ways in which foreign entanglements exacerbated both. The Farewell is often read as a warning about potential dangers that Washington feared the country might someday face, but it was just as much a lament about ills that he was sure had already beset it.

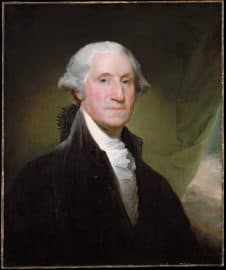

Washington’s 2nd inauguration (1793)

Although Washington lived only three years beyond his exit from the presidency, the state of American politics during his short retirement confirmed his darkest fears. Partisanship reached a fever pitch during the early years of the Adams administration, in the midst of the undeclared “Quasi-War” with France, leading Washington to warn that “party feuds have arisen to such a height, as to … become portensious of the most serious consequences” and that they appeared unlikely to “end at any point short of confusion and anarchy.”

Washington came to believe that it was no longer individuals and their virtues but rather parties and their ideologies that determined the outcome of elections. He insisted to one correspondent that if the Republicans were to “set up a broomstick, and call it a true son of Liberty, a Democrat, or give it any other epithet that will suit their purpose … it will command their votes in toto!” By this point, Washington was convinced that not only Congress but also the American people had become thoroughly and irretrievably partisan—and he had always insisted, since his days at the head of the Continental Army, that republican government could not survive for long under such conditions.

Washington’s Farewell Address (1796)

In Washington’s own view, then, his political career represented something like the reverse of his military career: in politics he won most of the battles—the elections, the policy disputes—only to lose the broader war. Just weeks before his death in December 1799, he wrote to James McHenry, his former secretary of war: “I have, for sometime past, viewed the political concerns of the United States with an anxious, and painful eye. They appear to me, to be moving by hasty strides to some awful crisis; but in what they will result—that Being, who sees, foresees, and directs all things, alone can tell.”

Dennis C. Rasmussen is Professor of Political Science at Syracuse University’s Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs. He is the author of four books, including Fears of a Setting Sun: The Disillusionment of America’s Founders and The Infidel and the Professor: David Hume, Adam Smith, and the Friendship That Shaped Modern Thought, which was shortlisted for the Ralph Waldo Emerson Award. Click here for the 1st part of this blog series.

Dennis C. Rasmussen is Professor of Political Science at Syracuse University’s Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs. He is the author of four books, including Fears of a Setting Sun: The Disillusionment of America’s Founders and The Infidel and the Professor: David Hume, Adam Smith, and the Friendship That Shaped Modern Thought, which was shortlisted for the Ralph Waldo Emerson Award. Click here for the 1st part of this blog series.