Among the American founders, Alexander Hamilton was easily the most consistent and unabashed proponent of a strong national government. His foremost dream for the new United States was that it would eventually achieve the kind of international prominence, military might, and economic prosperity that he saw embodied in the great European monarchies, especially Britain, and he believed that a vigorous or “energetic” central authority would be necessary to achieve these ends.

Alexander Hamilton, by John Trumbull

Many of Hamilton’s contemporaries – Thomas Jefferson being the foremost example – worried that a powerful national government would threaten individual liberty, but Hamilton insisted that stability and energy were necessary in order for liberty to endure. In his view, an impotent government is often a greater threat to liberty than a strong one and a dearth of effective political power is frequently more dangerous than an excess of it – as he believed the nation’s experience under the feckless Articles of Confederation had demonstrated.

Although the Constitution was designed to rectify this problem, Hamilton did not believe that it went far enough in doing so. At the end of the Constitutional Convention he resolved to defend the new charter as better than nothing – which he went on to do so ably in The Federalist – but he told his fellow delegates that “no man’s ideas were more remote from the plan [i.e., the Constitution] than his were known to be.” In his view, the narrow interests of the small states and the widespread but unwarranted apprehensions about centralized power had prevailed even within the group of (mostly) nationalist Federalists who had assembled in Philadelphia.

The Federalist

Hamilton therefore spent most of the 1790s seeking to strengthen the government in every way that he could dream up. As the nation’s first treasury secretary he developed a sweeping financial program that helped to put the country on a sound economic footing; as a pivotal member of President Washington’s Cabinet he fought to expand presidential power in both domestic and foreign affairs; and as the effective commander of the nation’s army later in the decade he sought to capitalize on the “Quasi-War” with France in order to build up the military.

Although he accomplished a great deal during these years, Hamilton was never satisfied that he had done enough. Jefferson and the Republicans, suspicious of his every move, continually whipped up popular opposition to his actions and prevented him from realizing the full extent of his vision. Around the time that Hamilton resigned his Cabinet position in 1795 he declared that his mindset was “discontented and gloomy in the extreme. I consider the cause of good government as having been put to an issue & the verdict against it.”

Statue Hamilton in D.C., 1st Secretary of the Treasury

Then, to Hamilton’s great dismay, Jefferson and the Republicans swept into power in the election of 1800 with a mandate to pare down the government’s powers still further. Although Jefferson’s conciliatory inaugural address initially gave him a glimmer of hope, Hamilton soon grew convinced that the new president was systematically rendering the government weaker and the country more vulnerable. In his view, the Republicans were betraying America’s founding principles as well as its greatest hero: “In vain was the collected wisdom of America convened at Philadelphia,” he wailed in one of his many public protests. “In vain were the anxious labours of a Washington bestowed.”

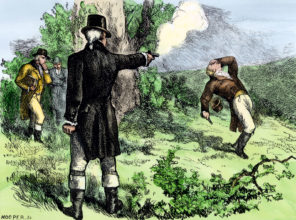

Burr-Hamilton duel (1804)

Hamilton’s confidence in the durability of the American regime ebbed and flowed over time, as it did for the other founders, but by 1802 it hit rock bottom. In a letter to his friend Gouverneur Morris he went so far as to describe the Constitution as a “frail and worthless fabric,” adding that “every day proves to me more and more that this American world was not made for me.” He told another correspondent that the survival of republican government in America would require “foundations much firmer than have yet been devised” in the United States.

By the time of his fatal duel with Aaron Burr in 1804, in short, Hamilton had concluded that the Republicans had already done irreparable damage to an already-weak government and that little but disorder and dissolution could be expected thereafter.

Dennis C. Rasmussen is Professor of Political Science at Syracuse University’s Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs. He is the author of four books, including Fears of a Setting Sun: The Disillusionment of America’s Founders and The Infidel and the Professor: David Hume, Adam Smith, and the Friendship That Shaped Modern Thought, which was shortlisted for the Ralph Waldo Emerson Award. Click here for other parts of this blog series.

Dennis C. Rasmussen is Professor of Political Science at Syracuse University’s Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs. He is the author of four books, including Fears of a Setting Sun: The Disillusionment of America’s Founders and The Infidel and the Professor: David Hume, Adam Smith, and the Friendship That Shaped Modern Thought, which was shortlisted for the Ralph Waldo Emerson Award. Click here for other parts of this blog series.