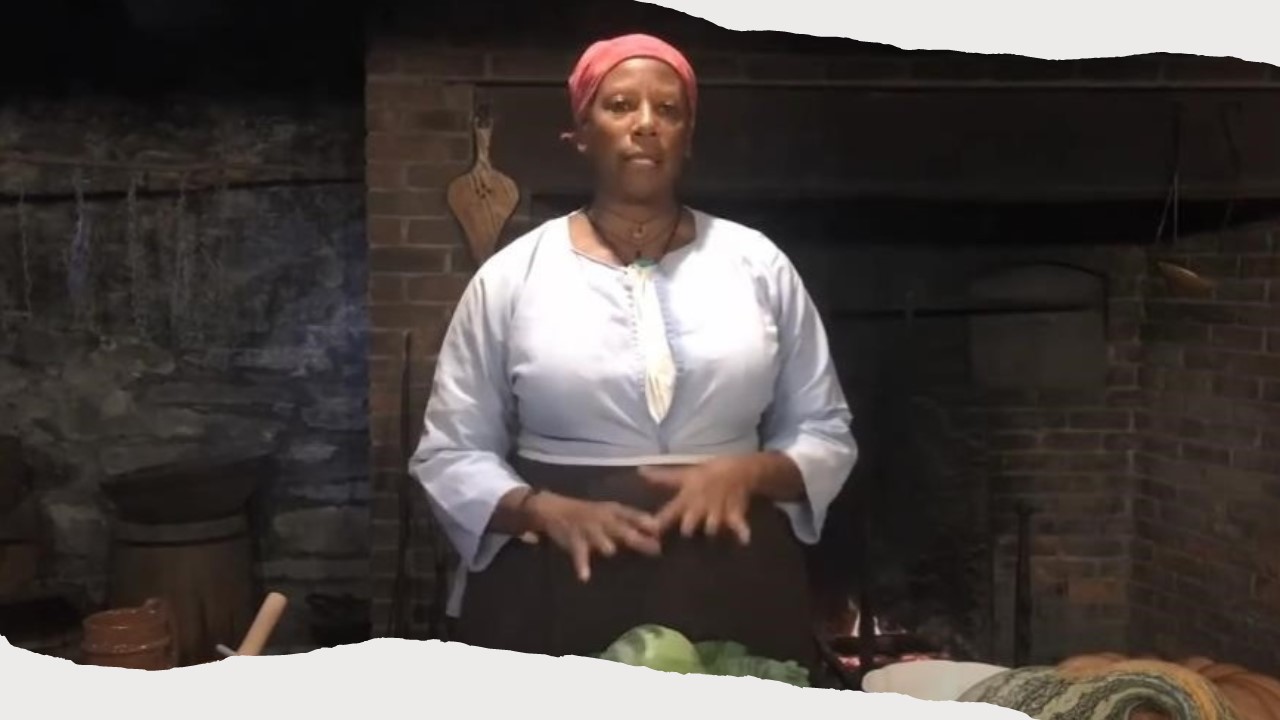

In early New Netherland and New Amsterdam new arrivals, Black and white, tried to recreate the world they had left. As historical sources are scarce and incomplete, historical interpreter and culinary historian Lavada Nahon uses deep empathy and imagination to depict the sensory world of the enslaved.

It is easy to put the Africans on the same playing field as the Europeans in their sensory experience of New Netherland. To imagine that they, like the Dutch, could immediately begin recreating, reconstructing their home world in the New World, bringing forth those deep sensual parts of human experience that they had left behind in Africa. But believing that they could do so in a timely manner means negating their everyday reality.

Sense

So how did the Africans get a sense of the Dutch and New Netherland through sight, sound, taste, and touch, while at the same time figuring out how to reproduce those of their homelands in North America? They were not like the Europeans. They did not arrive as their equals, ready to build a life they had dreamed of, one where they would leave a profound legacy and wealth that would last for generations. Instead, the Africans arrived as commodities. One or two at a time mixed in with other goods, or worse, chained in boats in which they had been for three to four months. And it would take the Africans more than a minute or two to figure out how to reproduce anything related to their homelands in such a hostile place. Although they eventually would. And it would leave multiple layers of lasting impact on North American culture. But in the meantime, before they could begin to do so, they had to become aware of where they were, and who the other people were, especially the Dutch. And they accomplished this primarily through sight, sound, touch, and taste.

For us to consider this process, and what they learned, we need to resort to documents and material culture that reference them, or what they themselves left. I believe we also need to engage the magical realm of our imaginations. We need to add our imagination to the words that we so commonly hear when we speak of the Dutch, and by doing so we can expand our empathy to see what it may have been like for the Africans as they got a sense of the Dutch through what they saw, what sounds they heard, what taste they experienced, and what touch they did or did not receive.

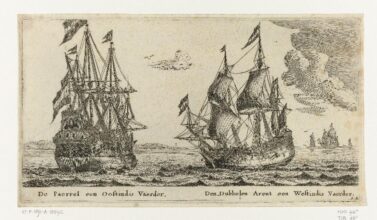

The ships Paerrel and Dubbelen Arent

Arrival

A few years after the Dutch claimed the landmass that would become New Netherland twenty African men and women with Eurocentric names were captured by a Dutch West India Company ship on a privateering trip. It is with them that the journey into consideration begins. Because their experiences of the sounds, smells, taste, and touch of the Dutch would be repeated by Africans and their descendants in New Netherland, and then in New York for another two hundred plus years, until at least 1842, when the last man bound to servitude on the landmass that was New Netherland was finally freed.

Although they would live in New Netherland for the rest of their lives, I believe their experience of getting to know the Dutch began at the point of their capture, just a bit earlier, perhaps when their noses were full of the smell of salty sea air, and then gun powder. When the air was scented by a mixed stench of sweat, and fear, while they felt strengthened by adrenaline and then overcome by fatigue. We can also add touch into this scene, perhaps that of a fist against a nose or jaw, or the butt of a pistol which would add to the mixture of smells the tanginess of fresh blood. Touch will shift to include the continuously painful rasping bite of rough hemp rope against their skins, rubbing sores on their wrist, and ankles, if not their necks.

When they entered New Netherland properly, their clear sight may have fled them momentarily as they stepped into the sunshine from the dark hull of the ship. The soundscape perhaps overwhelming them with a mixture of the familiar and the strange. The gentle lapping of water against the side of the boat. The cleaner scent of briny river water in their nostrils. Their ears full of human sounds, shouting and raised voices from the ship, people talking from the shore, bird calls, and all of it a bit too much. I can imagine them straining to pull apart the languages, hoping to catch a word or two they could understand, perhaps a bit of home, spoken in the sailors’ pidgin tongue.

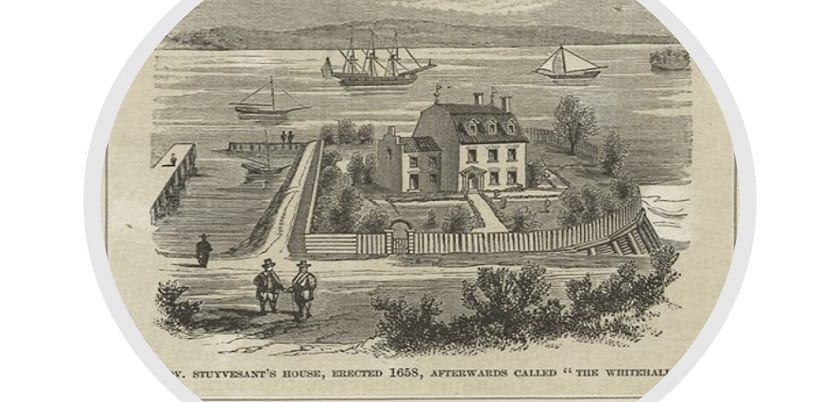

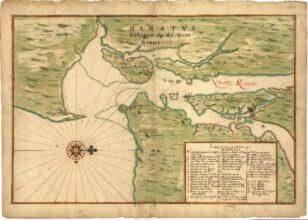

Manatus map by Johannes Vingboons (ca. 1639)

Land

Uninvited touch would be present in their lives from that point on. The shove from behind to get them to move along, the quick hit of bumping into their fellow man as they are hurried off the ship and into whatever muddy, dirt track they were directed to. All of this would probably happen before they would be allowed to eat, drink, or lay down on chilling earth somewhere to rest. There, they would be allowed to continue to smell the ugliness of themselves, a mixture of outrage, fear, urine, and shit.

This imposed nauseating aroma would become intertwined with newly arrived Africans, and is unfortunately a mainstay of information shared with Black children learning of the transatlantic slave trade. Whether the enslaved were mixed in with other cargo, or by the boat load directly from Africa, it is the scent of cruelty endured that is forever remembered. It has been said that it was this profoundly putrid perfume emanating for a slave ship in New Amsterdam’s harbor for several days that pushed at the edges of the colonists’ sensibilities, one more thing brought on the breeze to aid the English in their takeover of New Netherland.

Sorting out which one of the attacks on their senses they had to master first, of course, it was the taste of a new language on their lips and tongues that surely became their primary point of focus. Their mastery of it would lead some of them to the hallowed halls of the West India Company’s headquarters in Amsterdam to fight for pay they felt they deserved, and eventually to fight for a half-enslaved status, that the Dutch labeled half-freedom. But master it they did—like those who arrived after them and their descendants bound to the Dutch—to the point that it lingered within New York’s Black community well into the nineteenth century, and helped to create the prominent web of scars Sojourner Truth deftly displayed to the sight of others as she referenced her ten-year old self as Isabella Baumfree, who only spoke and understood Dutch, and was beaten by her new enslaver whose only language was English.

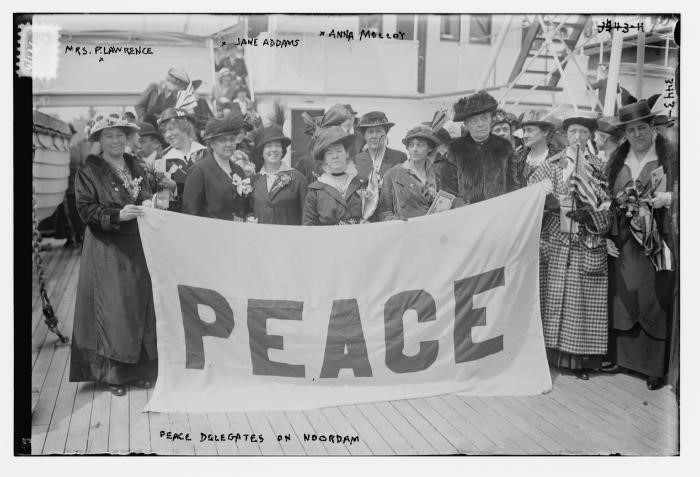

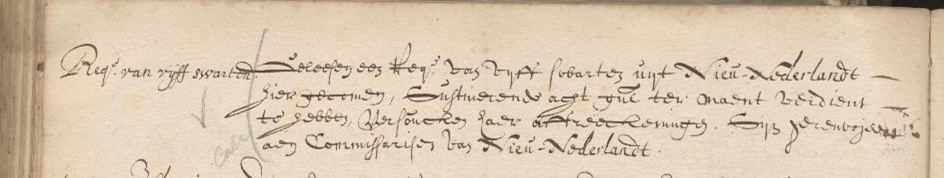

Excerpt from the resolution book the board of directors of the West India Company in Amsterdam *

Silence

The sound of silence would slowly creep in and become a major part of the lives of the enslaved in New Netherland. Their languages were in the air, but eventually would be stopped all together. Laughter, full-throated healing laughter, was quickly hushed as regulations were put in place, especially to maintain the sanctity of Sunday, the one day they perhaps had off. Africans and their descendants rarely relax in silence. Sounds, music from voice or instruments, chanting, drumming, singing, humming, that’s the usual way of things. But for the those early into New Netherland the soundscape would have been full of many noises, loud and low, the moans of grief, the cries of young children, not understanding what had happened to their parents, to themselves, the gagging sound of swallowed unspoken words, the desperate pleas of mercy as manacles were locked, whips were applied.

But gone was the rhythmic pounding of mortar and pestle to smooth boiled yams into eatable paste. Drums and the amazing variety of beats calling the sacred to prayer or to deliver a message to others miles away. The twang of strings attached to gourds, that would create the many enslaved fiddlers found in New York history later in the colonial period. They would not be gone forever, but it would be a while before they would be heard again at Pinkster or at all.

It would not be long before the needs of the Dutch would open up a world of memories for the African men enslaved by the Company. They would again become warriors, protecting themselves and those they knew, and touch the cold metal of weapons, while courage flowed through their veins. At the end of the day, when hunger turned their bellies, they may have longed for their mother’s cooking, yet, they would adjust to the unfamiliar foods feed them, the coarse grains of maize porridge, rubbing between their teeth and gums. Tasting its unfamiliar flavor again and again. They would drink soured buttermilk, or maybe discover the bitter taste of beer, but whatever it was they tasted, their remains speak clearly: it was not enough.

Women

The first arrival in 1627 also marked the moment women began their journey learning the sounds, smells, taste, and textures of Dutch New Netherland. Like the men, their introduction to the new world around them also began on the boats. As their skin crawled with filth, and their scalps itched with lice. Far too many would feel the rough callused hands of horny sailors, and the searing pain of rape. In their new homes they would have to manage the reality of pregnancy while they struggled to maintain their sanity. The sounds of their own cries would mix with those of their newborns, in the bloody mess of childbirth. The sight of a new shade of human cargo labeled yellow would be added to the mixture of those around them.

Understanding the differences in the sounds of an enslaver’s voice, the mellowness of a calm exchange, the lilt of annoyance, the thin line between annoyance and anger could often make the difference between a moment of peace or days of pain. The smells of sickness, the rot of dying, the taste of fear, were just some of the commonalities of life they may have experienced before but now took on a whole new level when Dutch New Netherland was in the house and North America was their new world. Their survival would depend upon their keen awareness of everything, all of their senses on high alert, allowing them to move through the days, months, and years, that would take them from the edge of stark survival to the center of humaneness.

Cold

All those Africans would understand cold like never before. They would shiver under thin scratchy wool blankets and remember the warmth of another sun. In doing so they would help other Africans newly arrived in New Netherland to cope with the world of the Dutch and its overwhelming enormity, while they constructed nkisi and prayed for relief. After years of work, some of those first men would settle back into themselves, and push for rights, and privileges, bringing the women they had taken to wife along with them. Even as others just blocks away would remain in chains, feeling the coarse rough weight of iron on their ankles, linking them to others day in and day out.

The small group of half-enslaved would open the world for those bound fully in slavery. They and others were granted the privilege of land and would soon see the work of their hands grow, improving their lives. Perhaps the newly hoed rows of fresh vegetables would replace other sights held in their recent memories. The hand marks left on the face of a friend who had been slapped for daring something beyond their station. Together all of the enslaved would come to understand and see the subtle signs of body languages and hear the tonal inflections of their Dutch masters that impacted their every moment. They begin to understand and avoid touch as much as possible.

Food

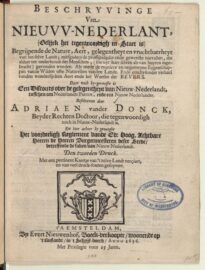

Van der Donck’s ‘Description of New Netherland’

As a culinary historian I often find myself lost in the luscious sounds, tastes, smells, and textures of historic Dutch kitchens. Reading Adriaen van der Donck while strolling through a historic garden, it is easy for me to imagine what it must have been like for those first African women being trained to cook. Seeing them in my mind walking through gardens in the backs of New Amsterdam townhouses grasping young weeds they pulled from raised beds, harvesting fragrant fruit off trees on a fine summer day. More often than not however, I seek to understand the path those same women most have traversed as they struggled to get a sense of balance in a kitchen they did not understand. Cooking is an intensely scented experience. And a job that demands your full attention to everything all at the same time unless you are willing to pay a variety of tolls for your distractions.

For the enslaved African women, coming off the boats, with the worst kind of post-traumatic stress disorder into a world where the breath of the woman facing them reeked of beer and onions, where the sounds of that woman were unintelligible, and the air was full of words they do not understand, sights of a roaring fire, pancake skillets, and strange art on small white squares attached to the walls were so foreign that they could only …what?…shrink back in fear or stand there in silent horror?

Cooks

It is for this charter generation of cooks, women in the most dangerous jobs, that we have nothing but our imagination to help us begin to understand how they could get a sense of the Dutch and their new lives in New Netherland. What it took for them to master the feel of wheat in all its various batters and doughs, from smooth, lump free, and runny for waffles, wafers, and pancakes, to malleable pounds of it mixed with just the right amount of yeast and water, and formed into round loaves for bread or smoothed between their hands into nicely shaped rolls for the bakers to cook off. Peter Rose, the noted Dutch food historian, makes clear that the Dutch love bread and beer, and these two food staples open the way for some of the most horrific beginner’s lessons into Dutch food culture for women who came from a place where neither existed. For it is the daily imbibing of beer that may have created an impatient teacher, a woman who would rather be somewhere else other than leaning over a hot fire. And it was the mastering of wheat, the most beloved and finicky wealth-producing grain for New Netherland and later New York, ground into flour that would take the enslaved women years to figure out. Along with bread, there are so many dishes that are common in Dutch culture that do not exist in West Central Africa. Actually, most of them, with the exception of fish. The rows of herbs, the variety of root vegetables, the peas, and then there is the entire new world pantry.

How something feels at different stages of preparation, how it smells as it cooks, how the sounds shift you from one point in the process to another, all of these are the unwritten instructions for every dish laid on every table for every meal. In recreating recipes found in the Sensible Cook, not the fancy things, but simples ones like pea soup, unskilled students I teach find it interesting when they ask me when to add onion and carrots to the melting butter in the pot and my reply is “when it stops making noise.” Those instructions would show up in an eighteenth-century cookbook, but in the years of Dutch New Netherland, well…just one of many, many things they had to get right that someone may not have remember to tell them because they grew up seeing it, knowing it, and simply didn’t think about it. Why are such small things important? Because the lives of the enslaved Africans depended upon it.

Recipes

When we look at the historic collections around New York State and note the number of waffle irons, pancake pans, wafer irons, we see them as lovely pieces of art and envision deliciousness. We look at the handwritten recipe books, and admire the countless recipes for the varieties of these common dishes, yet, we never give thought to what it took for an African woman to make thin, crisp, lightly brown, melt-in-your-mouth wafers or what may have happened to her when she failed. We don’t consider the pain of burned palms from the heat of the handles after hours of trying. Her aching arms, her sore back. We choose not to envision the touch of a whip on her back when she fails, embarrassing her owner. Nor do we consider what may have happened to an African woman who simply was not a good cook, even after months of trying.

The enslaved African cooks would have to sharpen their ears, along with their knives. They would learn from Dutch women to smell for levels of delicately scented vegetables in a room full of wood smoke. They would learn to feel the texture of pounded spice or milled pepper for bits that were too large and still needed to be worked. They would learn to see and watch the ripples roll across hot fat and eventually understand just when to add the oliekoecken, how to slip those soft balls of dough studded with dried fruit, apples into it, and not have their hands and arms laced with blisters.

For each and every one of the multitude of fruits, vegetables, fish, shellfish, birds, pigs, and cows that Van der Donck listed in A Description of New Netherland, there was a recipe that a Dutch woman had to teach to an enslaved African. All of that knowledge, all of that Dutch, not West Central African, foodways knowledge had to shared. And we don’t speak of what would have happened when the room smelled of burned butter or worse. We don’t think to discuss the taste of the grit of ash on the edges of waffles, or the waste of expensive spice. We talk about the oysters and clams, yet we fail to dive into what it would have taken someone unfamiliar with them to open the shells. Those never-to-be-discussed tidbits remain unspoken because they don’t show the quaint fantasy of Dutch women forever hovering over jambless hearths. The reality is famed she-merchants like Margaret Hardenbroeck didn’t spend all of their time in the kitchen or taking care of their children. They had things to do, wealth to build, more commodities and enslaved to trade.

Traditional Dutch kithen wiht jambless hearth

Mastering

While mastering their crafts, any of the things they did, the enslaved Africans were very aware of the sounds, smells, touch, and tastes of the Dutch around them. Because everything they failed to do to the satisfaction of their enslavers came with a price. The sounds and gestures of the Dutch woman transferring her knowledge who runs out of patience and hits with hand, spoon or whatever is there. To the men building houses, paving roads, steering boats, there was very little room for failure.

The enslaved developed keen eyesight to detect the most subtle of shifts in Dutch bodies. They learned to hear the rising and falling cadence of their breath, the unevenness of their tones. They became acutely aware of their joy and pleasure or their dissatisfaction simply by looking at them, and probably not directly but out of the corner of their eyes while they were busy trying to do whatever it was they were doing.

Other African women developed a keen awareness of the various textures of Dutch New Netherland within their sphere. The silky skin of babies, even as they dream of their own, no longer close enough to touch. They would taste the saltiness of their tears as they polish the pewter plates until they looked like silver or spun flax until their fingers bleed. They learned to ignore the splinters in their hands as they churn butter for hours, or the burn of salt in the cracks of their skin as they fill another firkin.

Within the forty years of Dutch New Netherland, it would not be long before the strength of the Africans allowed them to shift their attention from survival to acceptance, existence to growth. Their belief in their humanness would give them the strength to fight back and demand more, even as laws were constructed to ensure they had less. Including the children of the half-enslaved, those they had, and those they may have in the future. Laws that may not have been acted upon but were created all the same. Because, as much as we want to see them as indentured servants, it was clear that the Dutch did not.

Dutchness

They may have sat in Dutch churches hearing words of a new god while also remembering the dikenga, the four movements of the sun, and that it was important to retain their dignity and self-control so they could return, back to their family, back to their culture, back to Africa. They may have baptized their children while calling upon Olodumare and the Orixa, entreating Exu to open the way, so their prayers could go heavenward, and their lives could be eased. They would find the strength to recreate some of the sounds of Africa, but the tastes would be harder in their middle colony location. They would adjust to the texture of the coarse fabrics they wore, and long for silky palm cloth, while remembering the near nakedness of their arrival. They would dance, they would find joy, and express their full humanity as often as possible even as others denied it. They would remember sounds of their birth names, so unlike those they’d been forced to answer to, and give them to a child before they were gifted, bequeathed, or sold to another. Their hands would remember how to knap bones for tools for their own use, even as they lay in the garrets or in damp wet cellars on hot summer nights, trying to not flinch when they heard the click of the lock keeping them in place.

They would eventually have an impact on all the Dutchness around them, and make it clear that they, children of Africa, were here in Dutch New Netherland. Now, well now, they push the echoes of their voices onto the wind so we can hear them in the rattle of glass in old Dutch houses. They left carvings on rafters or corn cobs in garrets, crystals in doorways and other oddly but purposefully placed objects, and have us turn to African cultural records to learn, and not assume, what they were there for.

They reach through the thinness of the worlds and touch us with their energy so we shiver when exploring the garrets and cellars where they lived. They lift the veils drawn over jaded eyes and show themselves in documents that have been read time and time again, so we can finally see their names, count their numbers. They put rocks in our paths so we stumble or stub a toe against it while we walk through the fields where they worked. They move a hand so it will find the right place on a historic brick so their hands can once again touch another.

Survival

They got a sense of the Dutch and because of that they survived. And today through archaeology, through documents, material culture, and sometimes just plain weird feelings, they are reminding us that they were here in Dutch New Netherland. That they got a sense of the Dutch so we can now have a sense of the Africans. That they became part of New Netherland, because they understood that their lives, and those of their descendants depended upon them understanding the sights, sounds, tastes, and touch, the Dutch imposed upon them for their own benefit and learning from them. That by mastering the impacts of cruelty, brutality, and dehumanizing behaviors, the sensual assaults would allow them to move from commodities back to full human beings. And that we who study and share this history with the public, must open up and be honest, about the layers and varieties of sights, sounds, tastes, and touch the Africans experienced because of the Dutch, and stop pretending that they were not here, or that they were treated more kindly, more gently, more equitably because they were in the world of Dutch New Netherland, because they were not.

* “Read the request of five Blacks who arrived here from New Netherland. They maintain to have earned eight guilders per month and request to be paid. They are referred to the Commissioners of New Netherlands.”

Lavada Nahon is a culinary and cultural historian. Since 2020, she has served as Interpreter of African American History at the Bureau of Historic Sites of the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Lavada has worked as an independent contractor at a variety of state historic sites and other museums. She has a wealth of experience interpreting the lives of free and enslaved African Americans across the mid-Atlantic region, with an emphasis on the work of enslaved cooks in the homes of the elite class.

Last year The Dutch National Archives commissioned historian Jaap Jacobs to produce a series of 24 blogposts, 12 written by himself and 12 by co-authors, on the 400 year relationship between the Netherlands and the United States. Click here for the other parts.