During a late evening walk, journalist Joske Meerdink decided to turn right and go across the local graveyard. It lead to an unexpected find that sets off a voyage of discovery, taking Joske across the Atlantic. As she pieced together the story of a group of nineteenth-century Dutch migrants from the village of Winterswijk in the east of the Netherlands to Sheboygan in Wisconsin, she discovered personal connections previously unknown to her.

I love to make evening walks in the town of Winterswijk, where I was born. The Dutch habit of keeping curtains open makes strolls resemble visits to a museum, with the windows framing paintings that offer ever-changing views. I like to discover routes to find new, unfamiliar places. One evening, in December 2020, I pass the old graveyard of Winterswijk, a place that usually gives me the creeps. For some reason—I still don’t know why—, I decide to walk across the graveyard this time. I immediately spot a brightly lit memorial: two bollards holding up a colorful plaque. The sign reads: “The Phoenix Tragedy, 1847.” As I read the text aloud, it immediately becomes clear to me that the passengers—people from my own town—must have gone through hell. But the question that really strikes is: why didn’t I know this? Why did nobody, not my parents, nor a school teacher, ever tell me about this tragedy?

The memorial at the Oude Begraafplaats in Winterswijk

The memorial succinctly explains what happened on a cold night on Lake Michigan in late 1847. Eighty-four people from Winterswijk, including forty-eight children, had left their home village and travelled almost five thousand miles to the shores of Wisconsin. When their ship, the Phoenix, was near Sheboygan, its final destination, the engine room caught fire, the ship went down, and 154 immigrants lost their lives. Only forty-three people survived, of which ten belonged to the Winterswijk group. They settled in and around Sheboygan. The memorial includes all the names of the passengers, victims as well as survivors. I recognize many of the family names and begin to wonder whether members of my own family were among them. But other questions pop into my head too: why did so many people from Winterswijk go to America? What exactly happened during that fateful night? And has the wreck of the Phoenix ever been found? I walk home and start up my computer. Searching the internet for information about the tragedy takes me well beyond midnight. The story has taken hold of me and it won’t let go. I know I need to “do something” with it, but I don’t have a specific plan as yet. A year later the chief editor of Omroep Gelderland (Gelderland Broadcasting), where I work, asks me if I have ideas for a new podcast series. Yes, I do! I quickly draft a proposal and I am off on an historical adventure of several months, chasing the answers to questions that have been running through my mind from the moment I clapped eyes on the Phoenix memorial.

Why go from Winterswijk to Wisconsin?

August 1847. Winterswijk is steeped in deep poverty. Most people earn their living by farming. Many have a home loom or are wheelwrights—building wooden wheels—to add to the family income. It is a hardscrabble life and many long for better prospects. In 1846, no less than 318 people left Winterswijk to seek their fortune in America. As Winterswijk had only about 7,000 people, everyone knew someone who had left. Some parts of the town were almost depopulated. Winterswijk contributed one third of all Dutch migrants to the U.S. in 1846. Of course, it wasn’t just Winterswijk, people from other parts of the Netherlands left for America too. Poverty was an important push factor, but there was no single reason to leave. People don’t just up sticks and leave, they mull things over. Many motives coalesced in the process of pondering. A number of Winterswijk farmers were tenants, tilling the soil that was owned by large landowners, who retained semi-feudal rights well into the nineteenth century. A tenant farmer had few opportunities to acquire land of his own and if he had multiple sons, their chances were limited. With the population increasing continuously and harvests failing at times, due to for instance potato blight, famines were common. In areas in Germany, adjacent to Winterswijk, bad economic circumstances had already stimulated emigration. The stories about the land of unlimited possibilities spread across the border and rolled into the eastern parts of the Netherlands like an unstoppable wave of good tidings.

Winterswijk and surrounding villages in 1845.

Friends and family members who had already made the trip tried to persuade those who had stayed to follow. Jan Albert Beukenhorst from Winterswijk was one of them. In June 1845, he wrote:

“Beloved friends! The land is good here. We do not consider it less healthy than in Gelderland and it is the best in the whole of America. A farm laborer can earn more here than with you. It was hard for me to leave Winterswijk, but I wish never to be there again. Those of low descent here are equal to the wealthy, one does not need to doff one’s cap to anyone. Beloved friends, if you can, come over here, so that you can live well in your remaining days.”

For the people who ended up on the Phoenix, the most important motive was faith. In the early nineteenth century most people in Winterswijk attended the Dutch Reformed Church, but for some it was becoming too lax and too liberal. Dissenting believers organised meetings of their own, which, when countered by prohibitions, went underground. From 1834 onwards, dissatisfied believers in many places in the Netherlands began to split off from the established reformed church. The Secession, as the movement was called, also affected Winterswijk. A group of secessionists built a church of their own, the Zonnebrinkkerk, but that did not stop the continuous persecution by the former co-religionists. The idea of creating communities of their own in the United States slowly began to take root.

In 1847, the group of Winterswijk secessionist decided in favor of group migration, along the lines of similar plans promoted by ministers such as Anthony Brummelkamp, Albertus C. van Raalte (who later founded Holland in Michigan), and Hendrick Scholte (founder of Pella, Iowa). The Winterswijk group set their eyes upon Sheboygan in Wisconsin, an area where a number of German migrants had already settled. The favorable conditions for faming were largely similar to those in their own area, the Achterhoek. So they sold their farm buildings, their cattle, and other belongings. The emigrants often left in the autumn, after selling the crops gathered at the last harvest to fund their journey.

Minister Hendrick Scholte

Not all were able to pay for their own passage, so, in an admirable display of solidarity, wealthier members subsidized those less well off. The migrants on the Phoenix did not just originate from Winterswijk. They were joined by people from Aalten, Dinxperlo, Wierden, Apeldoorn, and other places. All had taken a step that they must have contemplated for a long time. It was a major, life-changing decision to emigrate in the nineteenth century: what is the right time to leave, what do we need for the journey? All in pursuit of a better future, for themselves, but especially for their children. It was a leap into the unknown, as many had never journeyed beyond the next village. They had never heard a foreign language and had no idea what awaited them, except for the information contained in letters sent by relatives who had preceded them.

The Day of Departure

Dozen of horses and carriages fill the market square around the Jacobskerk in Winterswijk on Saturday, 21 August 1847. Departing families, including the Oonk and Reuselink families, take their leave from friends and acquaintances. The Oonk family—father, mother, three sons and three daughters—had lived in Kotten, a small village southeast of Winterswijk. The family load all their belongings on the carriage. One of the daughters, Johanna Oonk, keeps a close eye on a young man of another family engaged in the same activity. His name is Harmen Jan Reuselink, her beloved. He lived with his parents in Woold, south of Winterswijk, and decided to emigrate with his widowed mother, his half-brother with his wife and children. Their sister, Hanna Gesiena and brother Jan Hendrik Reuselink had departed earlier in 1847. It was hard to say goodbye as the journey was not without perils. Jan Hendrik gave his brother Harmen Jan a book of psalms, a present that he himself had received fifteen years previously. Brotherly love, in the hope of a safe journey, or perhaps in the expectation of a reunion? Nobody knows. When all farewells have been said, the carriages leave the market square. Harmen Jan’s hand reaches into his duffle bag and he touches the psalm book of his brother that accompanies him as he begins his journey. It may provide him with protection against God knows what.

The carriages took the departing families from Winterswijk to Arnhem, where they boarded a river boat to Rotterdam. From Rotterdam they went to Hellevoetsluis to board the sailing ship France, which had arrived from Baltimore with a cargo of tobacco for Rotterdam. The passenger accommodation on the ship was rather basic: badly-lit and overcrowded compartments with insufficient ventilation during bad weather. The ship sailed in late September and soon the landlubbers from Winterswijk had their first experience of life at sea. It is utterly overwhelming, but fortunately the passage only takes four weeks. The France reaches New York on 26 October and the some of the Winterswijk group knelt to thank the Lord for their safe passage. If they thought the most dangerous part of their journey—the ocean passage—was over, they were badly mistaken. They proceeded north via the Hudson River to Albany and then boarded a canal boat to take them to Buffalo on Lake Erie. The last stage of their journey was to cross the Great Lakes to Sheboygan.

In Buffalo the group took out tickets on the propellor steamship Phoenix. It is a brand-new ship, two years old, 43 meters long, 8 meters wide. Its double propellor made it a step up from paddle steamers. The ship carried cargo—mainly coffee and sugar— and about two hundred passengers, Dutchmen and Americans. Some of the Dutchmen had to stay behind. The ship was overbooked and it was not well-suited for passengers. For some reason, Harmen Jan Reuselink boarded the Phoenix, but the other members of his family did not. Harmen Jan joined the Oonk family and his Johanna. One of the other passengers was an American businessman, David Blish. He taught the Dutch children a few words in English. In return, they taught him some Dutch. The Phoenix sailed onto Lake Erie but encountered high winds and icy conditions on Lake Huron, which scared the passengers huddling below deck. After seeking shelter behind an island, the Phoenix entered Lake Michigan. The weather was still quite bad, but spirits were lifted as the passengers approached their final destination. They were close to starting their new lives, after a journey of almost three months.

The Phoenix on Fire

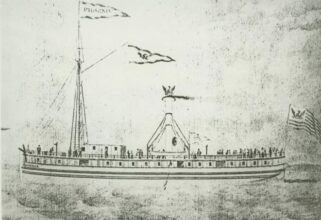

The Phoenix, 1845.

At Manitowoc, north of Sheboygan, the Phoenix made an unexpected stop to take in wood as fuel for the steam engines. After loading the captain decided to anchor and wait for the winds to subside. Some rumors tell us that part of the crew went ashore for a drinking bout. At 1am, the wind dropped and the captain decided that it was time to sail. He summoned the crew to return to the ship. Half an hour after departure one of the passengers, a young Irishman was woken by a noise from the engine room. He was an experienced steam engine mechanic and recognized the sound: the kettles were running dry, which overheats the engine. He tried to warn the crew, but they are still inebriated. They told him to mind his own business and for good measure gave him a bloody nose. Convinced that a disaster was about to happen, the Irishman woke up his family and told them to find a place in the lifeboats.

Another hour later, at about 2am, the Phoenix is about three or four miles from Sheboygan, close to the shore. One of the crew members notices smoke in the engine room. As predicted by the Irishman, the overheated engine has started a fire. Smoke, fire, and chaos awaken the passengers. They form a line to pass buckets of water, but it is useless. The engine room is located midships, dividing the ship into two parts. Flames shoot high up into the air, fueled by the wooden superstructure of the ship. Suddenly the metal smokestack tumbles over and disappears under the waves of Lake Michigan. Parents try to get their children into the lifeboats, often staying behind themselves. David Blish gives up his place in order to save Dutch children. He is still regarded as a hero in this tragedy. The lifeboats are lowered, but they are quickly filled beyond capacity. Passengers run to and fro on the deck in panick, screaming and shouting as as their clothing or hair have caught fire. Many see no other option but to jump overboard, after a last prayer. They don’t last long in the icy-cold water. One of Johanna Oonk’s sisters calls out: “Mother, mother, help me!” Then she sees her mother drown before her very eyes.

The lifeboats make their way through waters filled with wreckage and floating bodies. Many of those who jumped ship try to grip the sides of the lifeboats, which threatens to capsize them. The people in the lifeboats therefore hit them with the oars or with fists, to force them to let go. After some time the two lifeboats, carrying about forty people, arrive at a beach north of Sheboygan. They manage to light a fire to warm themselves.

Eventually the alarm was raised and the steamship Delaware, at anchor in the Sheboygan port, set course towards the burning Phoenix. When it arrived at the site of the disaster, not much was left of the Phoenix. It had burned down to the waterline. The site was eerily silent, no noise of roaring flames, no last prayers, no shouting or screaming anymore. The crew of the Delaware searched for survivors and managed to pick up three people. Then the Delaware towed what is left of the Phoenix to the Sheboygan port.

Surviving after Survival

Harmen Jan Reuselink and Johanna Oonk reached the shore in the lifeboats and survived, as did Johanna’s two sisters and her father. The tragedy ripped the family apart, as her mother and three brothers did not make it. Johanna’s sister Janna Hendrika throughout her life was terrified by fire, as she had seen half of her family perish through the flames. Slowly, the traumatized survivors began to build a new life. Initially, they lodged with hospitable people in Sheboygan, but later they moved to villages where immigrants from Winterswijk had settled. Land was readily available for new arrivals like the Phoenix survivors, as the U.S. government promoted efforts to bring the land under the plough. After acquiring land, the main task during the first year was bringing down trees to clear the land. The timber was used to build simple log cabins, not something the Achterhoekers were used to, but one had to make do. Everything the new settlers required they had to make, grow, or catch themselves. Was this the promised land? A better life? Yes, they had freedom of religion and they could now own the land they tilled. But it was a tough way to live.

Harmen Jan Reuselink and his family (ca. 1886)

Paying Homage

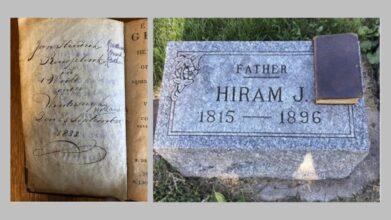

On a sunny day in July 2022 I stand at the shore of Lake Michigan, together with Rebecca and Kim Foster. They are descendants of Harmen Jan and Johanna and I was about to contact them after a search that took several months. From the water’s edge we survey the lake before us and in our mind’s eye we see the tragedy that happened here long ago. The psalmbook Jan Hendrik presented to Harmen Jan was on the Phoenix when the ship caught fire. Afterwards it washed ashore in a wooden chest. It suffered a bit of water damage, but it is otherwise in good condition. I know that, because I am holding it in my hand. The book was passed through the generations in the female line and thus came into the possession of the Foster sisters. The writing on the flyleaf at the front of the book reads in beautiful and elegant letters: “Jan Hendrik Reuselink, ’t Woold, near Winterswijk, 25 September 1833.” I run my fingers over the text and it hits me: here I am, in the middle of America, holding a book that was owned by someone from the town where I was born! And it’s not just that, while researching my genealogy I also discovered that I am related to Harmen Jan Reuselink as well as to Johanna Oonk. They both held this book in their hands, perhaps during the voyage, but most certainly after they had survived the tragedy. I hope it gave them the strength to come to terms with the awful memories of that dreadful night.

Harmen Jan and Johanna settled in Gibbsville in Sheboygan County. Other family members, such as his brother Jan Hendrik and sister Hanna Gesiena, who had emigrated earlier in 1847, also settled there. Six years after the Phoenix tragedy Johanna unfortunately died at the age of twenty-seven, leaving two small children (aged four and one) in the care of Harmen Jan. He remarried quickly, finding a new partner in Elizabeth Jansen, with whom he conceived five children. Thereupon Harmen Jan married for a third time, this time with a distant relative, Johanna. She was a granddaughter of Harmen Jan’s uncle and also bears the Reuselink family name: Johanna Reuselink Reuselink. Together they are blessed with another seven children, bringing the total to fourteen. The last one was born when Harmen Jan was seventy years old.

The Foster sisters and I drive to the “Jansen Cemetery” in Gibbsville, where Harmen Jan is buried. I suggest to Rebecca that we “return” the book for a moment to him as a gesture. She is touched and nodds in approval. She puts the book on his gravestone and for a short while we look at it together in silence. It is incredibly precious to have a palpable reminder of that terrible event on Lake Michigan on 21 November 1847, 175 years ago. The Phoenix failed to live up to its mythical meaning when it went up in flames. The Greeks believed that the phoenix was able to be reborn from its own ashes. But perhaps this Phoenix did the same, in a different way. Perhaps it was not reborn in the shape of a ship, but in the immigrants who survived. They rose from squalor to build a new life in a new world. Hundreds, perhaps thousands, have seen the light of day in America as a result of these brave immigrants.

Flyleaf of Harmen Jan’s book of psalms (left) – The gravestone of Harmen Jan Reuselink.

The psalmbook was not the only remnant of the tragedy that I encountered on my journey to America in the summer of 2022. As a result of the efforts of shipwreck hunter Steve Radovan and marine archaeologist Tamara Thomsen of the Wisconsin Historical Society’s Maritime Preservation and Archaeology program, we found an actual artifact of the ship itself: the smokestack! It tumbled from the ship during the fire and thus marks the site of the disaster.

I knew absolutely nothing of the Phoenix and its fate two years ago. Then I encountered the memorial at the old graveyard in Winterswijk and wondered whether any of my relatives had been involved. And now I am in Wisconsin, holding a book that survived the tragedy, a book that was owned by people who survived the tragedy and to whom I am even related. The story of the Phoenix itself evoked a powerful but also troubling fascination in me and the personal links enhance my emotions even more. Two years later my mission to tell the story and give it the attention that it deserves has yielded fruit. I never imagined that an impulsive decision to turn right during an evening walk could take me from Winterswijk to Wisconsin. So my advice: take an unexpected turn if the road ahead offers it! You never know where it may lead you.

About the author

Joske Meerdink, born and bred in Winterswijk, is a journalist. She works for Omroep Gelderland (Gelderland Broadcasting) as Digital Content Editor. In 2022 she made a podcast on the fatal voyage of the Phoenix.

Last year The Dutch National Archives commissioned historian Jaap Jacobs to produce a series of 24 blogposts, 12 written by himself and 12 by co-authors, on the 400 year relationship between the Netherlands and the United States. Click here for the other parts.