The Impakt Festival officially kicked off this Wednesday evening, and the first event was the exhibition opening at Foto Dok, curated by Alexander Benenson.

The Impakt Festival officially kicked off this Wednesday evening, and the first event was the exhibition opening at Foto Dok, curated by Alexander Benenson.

The works in the show circled around the theme of Soft Machines, which Impakt describes as “Where the Optimized Human Meets Artificial Empathy”.

Of the many powerful works in the show, my favorite was the 22-minute video, “Hyper Links or it Didn’t Happen,” by Cécile B. Evans. A failed CGI rendering of Philip Seymour Hoffman narrates fragmented stories of connection, exile and death. At one point, we see an “invisible woman” who lives on a beach and whose lover stays with her, after quitting a well-paying job. The video intercuts moments of odd narration by a Hoffman-AI. Spam bots and other digital entities surface and disappear. None of it makes complete sense, yet it somehow works and is absolutely riveting.

After the exhibition opening, the crowd moved to Theater Kikker, where Michael Bell-Smith, presented a talk/performance titled “99 Computer Jokes”. He spared the audience by telling us one actual computer joke. Instead, he embarked on a discursive journey, covering topics of humor, glitch, skeuomorphs, repurposing technology and much more. Bell-Smith spoke with a voice of detached authority and made lateral connections to ideas from a multitude of places and spaces.

In the first section of his talk, he describes that successful art needs to have a certain amount of information — not too much, not too little, citing the words of arts curator Anthony Huberman:

In the first section of his talk, he describes that successful art needs to have a certain amount of information — not too much, not too little, citing the words of arts curator Anthony Huberman:

“In art, what matters is curiosity, which in many ways is the currency of art. Whether we understand an artwork or not, what helps it succeed is the persistence with which it makes us curious. Art sparks and maintains curiosities, thereby enlivening imaginations, jumpstarting critical and independent thinking, creating departures from the familiar, the conventional, the known. An artwork creates a horizon: its viewer perceives it but remains necessarily distant from it. The aesthetic experience is always one of speculation, approximation and departure. It is located in the distance that exists between art and life.”

In the present time where faith in technology has vastly overshadowed that of art, these words are hyper-relevant. The Evans video accomplishes this, resting in this valley between the known and the uncertain. We recognize Hoffman and he is present, but in an semi-understandable, mutated form. We know that the real Philip Seymour Hoffman is dead. His ascension into a virtual space is fragmented and impure. The video suggests that traversing the membrane from the real into the screen space will forever distort the original. It triggers the imagination. It sticks with us in a way that stories do not.

What Bell-Smith alludes to his talk is that the idea of combining the human and the machine won’t work…as expected. He sidesteps any firm conclusions. His performance is like the artwork that Huberman describes: it never reaches resolution and opens up a space for curiosity.

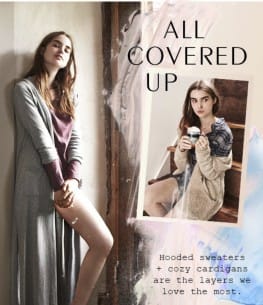

Later he displayed slides of Photoshop distasters, a sort of “Where’s Waldo” of Photoshop errata. Microseconds after viewing the advertisement below, we know something is off. The image triggers an uncanny response. A moment later we can name the problem of the model having only one leg. Primal perception precedes a categorical response. Finally, everyone laughs together at the idiosyncrasy that someone let into the public sphere.

Later he displayed slides of Photoshop distasters, a sort of “Where’s Waldo” of Photoshop errata. Microseconds after viewing the advertisement below, we know something is off. The image triggers an uncanny response. A moment later we can name the problem of the model having only one leg. Primal perception precedes a categorical response. Finally, everyone laughs together at the idiosyncrasy that someone let into the public sphere.

After Bell-Smith’s talk we had a chance for eating-and-drinking. Hats off to the Impakt organization. I know I’m biased since I’m an artist-in-residence at Impakt during the festival itself, but they certainly know how to make everyone feel warm and cozy.

Next up was the keynote speaker, Bruce Sterling, who is a science fiction writer and cultural commentator. He boldly took the stage without a laptop, and so the audience had no slides or videos to bolster his arguments. He assumed the role of naysayer, deconstructing the very theme of the festival: Where Optimized Human Meets Artificial Empathy.

Next up was the keynote speaker, Bruce Sterling, who is a science fiction writer and cultural commentator. He boldly took the stage without a laptop, and so the audience had no slides or videos to bolster his arguments. He assumed the role of naysayer, deconstructing the very theme of the festival: Where Optimized Human Meets Artificial Empathy.

Defining the terms “cognition” (human) vs “computation” (machine), he took the stance that the merging of the two was a categorical error in thinking. His example: birds can fly and drones can fly, but this doesn’t mean that drones can lay eggs. My mind raced, thinking that someday drone aircraft might reproduce. Would that be inconceivable?

Sterling tackled the notion of the Optimized Human with san analogy to Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment. For those of you that don’t recall your required high school reading, the main character of the book is Raskolnikov, who is both brilliant and desperate for money. He carefully plans and then kills an morally bankrupt pawnbroker for her cash. The philosophical question that Dostoyevsky proposes is the idea of a superhuman: select individuals who are exempt from the prescribed moral and legal code. Could the murder of a terrible person be a justifiable act? And would the person to judge this be someone who is excessively bright, essentially leaving the rest of the humanity behind?

In the book, the problem is that the social order gets disrupted. Raskolnikov action introduces an deadly unpredictable element into his village. With an uncertainty to the law and who executes it, no one feels safe. At the conclusion of the novel, Raskolnikov ends up in exile, in a sort of moral purgatory.

The very notion of the “optimized human” has similar problems. If select people are somehow “upgraded” through cybernetics, gene therapies and other technological enhancements, what happens to the social order? Sterling spoke about marketing, but I see the greater problem one of leveraged inequality. If there are a minority of improved humans who have integrated themselves with some sort of techno-futuristic advantages, our society rapidly escalates the classic problem of the digital divide. The reality is that this has already started happening. The future is here.

Bruce Sterling concluded with the point that we need to pay attention to how technology is leveraged. His example of Apple’s Siri system, albeit not a strong case of Artificial Empathy, is owned by a company with specific interests. When asked for the nearest gas station or a recipe for grilled chicken, Siri “happily” responds. If you ask her how to remove the DRM encoding on a song in your iTunes library, Siri will be helpless. While I disagreed with a number of Sterling’s points in his talk, what I do know is that I would hope for a non-predictive future for my Artificial Empathy machines.

Bruce Sterling concluded with the point that we need to pay attention to how technology is leveraged. His example of Apple’s Siri system, albeit not a strong case of Artificial Empathy, is owned by a company with specific interests. When asked for the nearest gas station or a recipe for grilled chicken, Siri “happily” responds. If you ask her how to remove the DRM encoding on a song in your iTunes library, Siri will be helpless. While I disagreed with a number of Sterling’s points in his talk, what I do know is that I would hope for a non-predictive future for my Artificial Empathy machines.

The Impakt Festival continues through the weekend with the full schedule here.