I had gotten pretty good about feeling lucky even before all this happened. But I’m now more conscious of my luck than ever, both in terms of the big picture – I am young, healthy, self-employed – as well as all the circumstantial reasons that have allowed me to experience the pandemic not as a catastrophe but as a novel interruption of my regular life.

My wife’s parents made it possible for us to leave our apartment building in Brooklyn and relocate to an empty house outside the city. We are “stuck” here with two of our closest friends and two cute dogs who don’t mind each other. The four of us spend our days doing work while sitting on couches; when we finish for the day, we take the dogs out to a field where they can run around, and in the evenings, we take turns cooking dinner. When it gets cold in the house, we can turn up the thermostat. There is literally nothing to complain about.

My wife’s parents made it possible for us to leave our apartment building in Brooklyn and relocate to an empty house outside the city. We are “stuck” here with two of our closest friends and two cute dogs who don’t mind each other. The four of us spend our days doing work while sitting on couches; when we finish for the day, we take the dogs out to a field where they can run around, and in the evenings, we take turns cooking dinner. When it gets cold in the house, we can turn up the thermostat. There is literally nothing to complain about.

The biggest luxury might be that we have full control over what we know about the outside world, and how much information we’re exposed to about the suffering we’re being spared. We could fill each day reading about people who are sick and dying; doctors and hospital staff who are making impossible decisions on little to no sleep; workers and business-owners who don’t know how they’ll recover their losses or start earning money again. I do read about all those things, and I do empathize and donate and mourn and worry. But I do so from the comfort of my temporary home. And the fact is I could choose to ignore it all if I felt like it.

Having this discretion insulates me from reality to a degree that should be impossible. It is a form of extreme luck that a stronger, less selfish person might try to redistribute. But I have convinced myself, conveniently, that there’s little I could give up that would help anyone else. It makes me wonder how the people without my luck – the people with loved ones who have died, who are waiting in food lines, who are risking their own health by going out into the world to help others – would conceptualize the difference between us, if they didn’t have more urgent things to think about. I wouldn’t blame them for hating my guts.

After I finish writing this, I will take my dog outside to pee; then I’ll give him breakfast and pet him while he sleeps on a literal tuffet. My wife and I have had him for 5 years now, and on countless occasions, during moments of acute work-related stress, we have glanced over at him and thought, “You have no idea what’s going on, you’ve never had to do anything, and nothing bad has ever happened to you.” All true. Lucky dog.

After I finish writing this, I will take my dog outside to pee; then I’ll give him breakfast and pet him while he sleeps on a literal tuffet. My wife and I have had him for 5 years now, and on countless occasions, during moments of acute work-related stress, we have glanced over at him and thought, “You have no idea what’s going on, you’ve never had to do anything, and nothing bad has ever happened to you.” All true. Lucky dog.

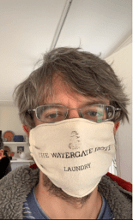

Leon Neyfakh is an American podcast maker. He created the award-winning podcast series ‘Slow Burn’, about the Watergate scandal and the Lewinsky-affair. His podcast ‘Fiasco’ deals with the hotly contested 2000 election between Al Gore and George W. Bush and the Iran-Contra affair during the Reagan administration. Leon Neyfakh visited the John Adams to talk about storytelling in the digital age in 2019.