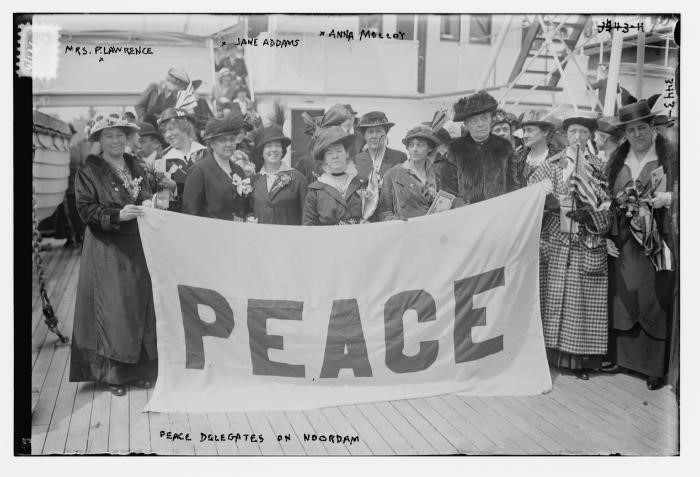

Social activism and the struggle for women’s suffrage in the early twentieth century brought together women from countries around the world, including the United States and the Netherlands. Mineke Bosch highlights how shared issues fostered a deep friendship between the American Jane Addams and the Dutch Aletta Jacobs.

Berlin, May 1915. Three feminists on an historical mission—Jane Addams and Alice Hamilton from the United States and Aletta Jacobs from the Netherlands—meet Wilbur H. Durborough in Berlin. The American photographer and filmmaker had travelled to Berlin with his cameraman, Irving G. Ries, to shoot footage for his war documentary With the Germans on the Firing Line. The project was financed by a group of businessmen from Chicago, where Durborough worked. It is likely that he was already acquainted with Jane Addams, one of the most respected women in the United States at the time. In the 1890s, she had set up the famous Hull House Settlement in a Chicago district where many different ethnic groups of migrants lived together. Initially Hull House aimed to provide privileged young women with meaningful employment, but it gradually morphed into an important centre for social practice and reflection on social work. Although virtually self-taught, Addams played an important role in the social debate on what we would now call integration or multiculturalism through her publications Democracy and Social Ethics (1902), The Spirit of Youth and the City Streets (1909) and the bestseller Twenty Years at Hull House (1910). In 1910, she was the first woman to be awarded an honorary doctorate by Yale University. She was accompanied on her European trip by Dr Alice Hamilton who had studied medicine and was a voluntary worker in residence at Hull House. She specialised in occupational disease and industrial toxicology and was a special investigator for the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Jane Addams, Alice Hamilton, Aletta Jacobs in Berlin, 21 May 1915.

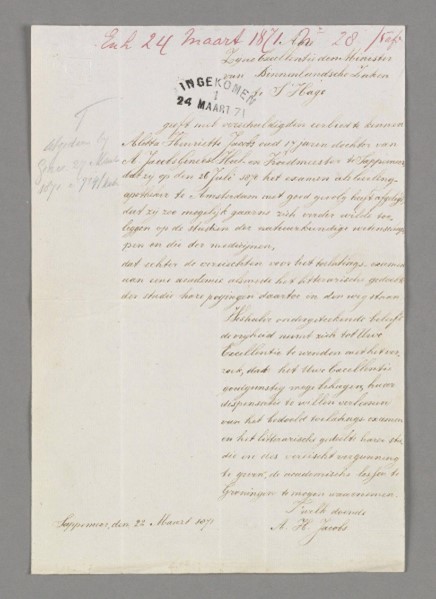

The third woman in the group was Aletta Jacobs. She was the first woman to enroll at a Dutch university and also the first to set up practice as a physician in 1879. In addition, she ran free clinics in deprived neighborhoods of Amsterdam, where she provided women with free advice on birth control, as well as technical support in the form of a pessary that she introduced in the Netherlands. As the Dutch Constitution stipulated that all citizens who payed a set amount of taxes were entitled to vote, Jacobs in 1883 tried to register to vote in the local elections of Amsterdam. She challenged the city council’s decision to deny her this right to the Supreme Court, to no avail. In reaction, the all-male committee drafting a new constitution proposed that women should be explicitly excluded from suffrage, and inserted ‘male’ before ‘citizens’ in the new Constitution of 1887. In 1894, Aletta Jacobs and others founded the Dutch Association of Women’s Suffrage, of which she became president in 1903. Subsequently the Dutch association built strong connections with other western countries, especially the United States. Thus Aletta Jacobs’ correspondence provides insights into her intimate friendships with leading American suffrage feminists, such as Carrie Chapman Catt, Anna Howard Shaw, and Jane Addams.

Request of Aletta Jacobs to be admitted as student at the University of Groningen

Durborough asked the three women to walk towards the camera which he had strategically positioned so that the Brandenburger Tor would feature in the background. And so they did, talking and laughing for a mere twenty seconds, giving us a glimpse of how they moved about in the past, with Jane Addams in the leading role, flanked by Alica Hamilton with the much smaller Aletta Jacobs patiently waiting her turn with a big smile on her face. This short clip of a long-lost movie allows us to share a brief historical moment in the year after the outbreak of the great massacre that the First World War turned out to. So what was the aim of the three women in visiting Berlin?

A Mission for Peace

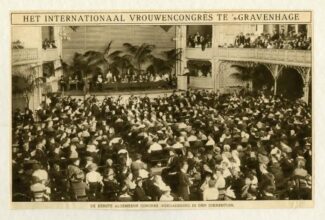

Their mission had started in the summer of August 1914, when telegrams began to crisscross Europe and the Atlantic, carrying ever more ominous messages of war. Immediately, feminists on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean sprang into action and organised marches and meetings to protest against the impending war, which they regarded as an atavistic and barbaric practice. As they were well connected through the International Woman Suffrage Alliance (IWSA), many suffragists wanted to raise their voice as women through an international conference, demonstrating solidarity among women across the belligerent divide. As the IWSA had always been strictly non-political and non-partisan (difficult though that could be), a ‘private’ intitiative was required to organize an international women’s conference in a neutral state. What better location than The Hague, which had hosted three international Peace Conferences since 1899 and where in 1913 the Peace Palace had opened its doors? Aletta Jacobs took on the task, relieved that she could finally do something, instead of being sidelined by war. Assisted by an able group of international organisors she put everything together in just two months. On April 27, 1915, the International Congress of Women kicked off in the large conference hall of the The Hague Zoo.

Jane Addams in a car in Chicago, 22 July 1915

The congress was an astounding success. It was attended by well over a thousand voting members, although the audience often numbered about two thousand. Unfortunately, only three British women could take part. They had arrived early, before the British government at the very last moment rescinded the twenty-five passports it had handed out initially. The British press vilified the British attendees, calling them ‘Pro-Hun Peacettes’ who held a ‘Pow wow with the Fraus’. The German women were also few in number, as many had been stopped at the Dutch-German border, with the exception of some early arrivals. In contrast, the American delegation consisted of forty-two women. They had been held up for a few days at Dover, but nevertheless arrived just in time for the grand opening. Jane Addams’ willingness to preside over the congress contributed considerably to its success.

In her opening address Aletta Jacobs indicated that the congress was not just an international call of women for peace. In her opinion, women had to fight for suffrage in order to obtain the necessary power to prevent war:

“Those of us who have convened this Congress however have never called it a peace congress, but an international Congress of women to protest against war, and to discuss ways and means whereby war shall become an impossibility in the future. We consider that the introduction of woman suffrage in all countries is one of the most powerful means to prevent war in the future, so that women, before the war-fever sets in, may be able to plan means and to produce conditions which would help to prevent the outbreak of war. But to accomplish this we need political power. Not until women can bring direct influence to bear upon Governments, not until in the parliaments the voice of the women is heard mingling with that of the men, shall we have the power to prevent recurrence of such catastrophes.”

The emphasis on women’s suffrage did not meet with support from all attendees. Several speakers pointed out that insistence on suffrage would do the cause more harm than good. Moreover, not everyone shared Jacobs’ high opinion of women’s peaceable disposition or of their ‘conserving’ qualities as mothers of the human race. Addams herself later stated that it would be impossible to prove that women per se were opposed to war.

Twenty Resolutions and Two Envoys

Over four days of proceedings, the 1915 International Congress of Women approved a total of twenty resolutions. Twelve resolutions had been sent out by mail in advance and the American delegation, sailing toward Europe on the SS Noordam, used its time on board to draft a number of amendments. Together with plans and ideas that had been developed by other peace organisations, the resolutions and amendments dominated the deliberations. The discussions during the congress ranged from Julia Grace Wales’ plan of continuous mediation without an armistice and the abolition of secret diplomacy to the right of minorities to self-determination, democratic control over decisions concerning war, and the establishment of international bodies, including a ‘league of nations’. Many of the ideas would later feature among the Fourteen Points put forward by Woodrow Wilson at the negotiations to bring World War One to an end. The Congress also laid the foundation for the future Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom as it formed an International Committee of Women for Permanent Peace, which temporarily established its headquarters in Amsterdam. But the item that sparked the liveliest debate was the proposal to send envoys to hand over the printed resolutions and proceedings of the congress in person to the heads of governments to the warring and neutral countries, including the U.S. President. Using all her rhetorical powers, the Hungarian Rosika Schwimmer delivered a final one-minute speech that proved to be decisive:

“Brains—they say—have ruled the world till to-day. If brains have brought us to what we are in now, I think it is time to allow also our hearts to speak. When our sons are killed by millions, let us, mothers, only try to do good by going to kings and emperors, without any other danger than refusal (Hear, Hear, Hear)!”

The International Congress of Women in session, April 1915

Jane Addams and Aletta Jacobs, though very reluctant at first, would be the delegation to the capitals of warring countries. They were accompanied by two unofficial envoys, Alice Hamilton and the Dutch Mien van Wulfften Palthe-Broese van Groenou. After a visit to the Dutch Prime Minister P.W. Cort van der Linden, and a few days in London where they met with Foreign Secretary Edward Grey and Prime Minister Herbert Henry Asquith, they set out for Berlin. Upon their arrival on May 19th, they immediately contacted their respective ambassadors to arrange appointments with the German Chancellor, Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg, and his Foreign Secretary, Gottlieb von Jagow. The American Ambassador, James W. Gerard, did not hide his disdain for Addams and Jacobs:

“Early summer brought also a number of cranks to Berlin. Miss Addams and her fellow-suffragists, after holding a convention in Holland, moved on to Berlin. I succeeded in getting both the Chancellor [Bethmann-Hollweg] and von Jagow to consent to receive them, a meeting to which they looked forward with unconcealed perturbation.”

Aletta Jacobs did not attend the meeting with Bethmann Hollweg, as the Dutch Ambassador failed to follow through. Nevertheless, the conversations of the delegation with the Chancellor and the Foreign Secretary were focused and frank, according to several reports. They discussed all the resolutions, with an emphasis on the resolution calling for a neutral conference and continuous mediation. The German statesmen both indicated that neutral countries should take the lead in bringing this about. The issue of women’s suffrage was brought up too, and Addams and Jacobs thus made clear that their advocacy was firmly rooted in feminist political thinking, which they fully embraced and which provided the impetus for the concerted international action of women for peace.

When they arrived back in Amsterdam at the end of June, the envoys could look back on having visited thirteen countries. They had met with twenty-one ministers, the president of a republic, a king, and the Pope. There was one last head of state to call upon: the President of the United States, who had often been mentioned as the best hope to initiate a neutral peace conference. The women were still working on publishing the proceedings when signs of dissent began to surface among the several ambitious peace activists. In August Aletta Jacobs suddenly booked a ticket to New York on the SS Nieuw Amsterdam, as Jane Addams and other American friends had—through intercession of Secretary of State Robert Lansing—arranged a meeting with president Wilson. Aletta Jacobs finally met Wilson on September 15, 1915. Of course, the visit was mainly of symbolic significance, but it was very important to Aletta Jacobs. She included a short letter that Wilson subsequently wrote to Addams in its entirety in her Memories ‘as a token of the President’s kindness’: ‘My dear Miss Addams’, the President wrote, ‘I warmly appreciate your kind letter about Dr. Aletta Jacobs. You may be sure that it gave me great pleasure to meet so interesting a woman.’

Letter from Jane Addams to Aletta Jacobs

War or Peace?

So, what did it all mean? How should we evaluate this undeniably plucky piece of international feminist demonstration of their political will and artful diplomacy? A common belief among feminists of the 19th and 20th centuries was that their struggle had to be international by definition. Women everywhere were oppressed and excluded by the laws, customs, and traditions in each of their countries and this implied that the bond between them was greater than with their individual nations. During the founding meeting of the International Council of Women in 1888, Elizabeth Cady Stanton expressed this belief as follows:

“[…] we do not feel that you are strangers and foreigners, for the women of all nationalities, in the artificial distinctions of sex, have a universal sense of injustice that forms a common bond between them.”

In recent historical interpretations, both feminist and conventional, the Hague International Congress of Women in 1915 has often been regarded as compelling evidence for this view. Here, women from various warring and neutral countries had overcome major obstacles and defied both hostile public opinion and their own government to literally and figuratively shake hands and show the world that their sisterhood transcended borders. Inherent to this interpretation is Jacobs’ and Addams’ roles as important peace apostles and as internationalists who, on the basis of their feminism, had set aside national aspirations to serve peace. Indeed, when Jane Addams was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1931, the presentation speech referred to the women’s congress in 1915 as ‘one of the finest and most promising events during the last great war’. Aletta Jacobs was credited for her role in the same breath:

“The initiative for this conference, which took place at the Hague in April 1915, came from the Dutch women, and it is only right to pay tribute to the memory of Dr. Aletta Jacobs, who stood at their head.”

Celebration of fiftieth anniversary of Aletta Jacobs’ doctorate, 1929

On the whole, the 1915 Congress of Women has not received much scholarly scrutiny and it thus requires careful consideration. Certainly, Aletta Jacobs and Jane Addams were passionate feminists and peace activists, but their drive to take on this task was shaped by personal motives and political opportunity as well. Aletta Jacobs, for instance, had more room to take a stance than feminists in other countries as the Dutch defined themselves as peace-loving by nature while simultaneously aspiring to a prominent role in international affairs. Such considerations may certainly raise questions, but it does not imply that the congress was without historical significance. The main protagonists themselves often showed themselves realistic about their efforts. For instance, just before arriving in The Hague, Emily Balch reflected on the collective experience of the American delegation on board of the SS Noordam:

“These days have been invaluable, they have welded us together and have revealed to a great degree our strong and weak points. I think one thing that is disarming is that though we are proposing to put forward all sorts of Utopian plans we do not ourselves greatly misconceive the situation. We do not suppose that we have power or knowledge or importance. […] It does take faith, but faith we have got and we do care. We know we are ridiculous, but even being ridiculous is useful sometimes and so too are enfants terribles that say out what needs to be said but what it is not discreet or ‘the thing’ to say and which important people will not say in consequence.”

Whether or not their actions were well-timed, the women were too gullible, or the peals of laughter in the press were justified, doesn’t matter. It did not cause their plans to fail. Rather, they did not succeed because as women they had no formal power, regardless of the issue suffrage. The warring countries did not seek reconciliation or peace, or at least they never did so at the same moment. Moreover, President Wilson followed his own plans in finding a road to peace. Addressing the American Federation of Labor Convention in November 1917, when he had already led the U.S. to join the war, he said:

‘My heart is with them [the pacifists], but my mind has a contempt for them. I want peace, but I know how to get it, and they don’t know.’ Of course, he did not, and his own plans came to grief just as ignominiously as the women’s attempt at a diplomatic solution. With hindsight, a number of contemporaries have observed that continuous mediation through a peace conference organised by neutral states was still a viable option. Addams and Jacobs may well have had the best papers to achieve this through their independent diplomatic mission. Be that as it may, the Congress of Women was one of the many attempts to stem the apparently inevitable tide of war. Or, in the words of Jane Addams: ‘Nothing could be worse than the fear that one had given up too soon and had left one effort unexpended which might have saved the world.’

About the author

Mineke Bosch (PhD Erasmus University Rotterdam, 1994) is Professor Emerita of Modern History at the University of Groningen. She has published extensively on the history of science, women’s and gender history, and international women’s movements, including a biography of Aletta Jacobs, Een onwrikbaar geloof in rechtvaardigheid.

Last year The Dutch National Archives commissioned historian Jaap Jacobs to produce a series of 24 blogposts, 12 written by himself and 12 by co-authors, on the 400 year relationship between the Netherlands and the United States. Click here for the other parts.