August 27, 1918

Your name is Zeferino Gil Lamadrid, a well-known Mexican carpenter from Nogales, Sonora. It is about 4 PM on an unbearably hot summer day, and you are finally heading back home from some business on the other side of the border with a bulky package under your arm.

For you – and for all other citizens of Ambos Nogales – crossing the border is something ordinary, something you are used to do since you were born. During your childhood, with your friends you could play and roam freely on that broad boulevard dividing the two towns. Those days are long gone: the Revolution in Mexico – with Pancho Villa’s raid in Columbus – and First World War have shaped a climate of distrust and hysteria.

Nogales, Sonora (ca. 1940s). To the right: railroad connecting Ambos Nogales with customs house in background.

You cross the dusty International Street and approach the railroad customs kiosk. You have already stepped onto Calle Internacional, when a US Inspector, suspicious for the parcel, urges you to turn around and come back for inspection. Hearing the order, you immediately stop and are about to turn to him, when you hear Mexican guards telling you to ignore it and keep walking, since you are already on Mexican soil. You are not sure what to do anymore: you freeze, with the heart in your mouth. Then a US soldier points his Springfield rifle at you, shouting to get back. You are terrified, you feel the adrenaline rushing all over your body.

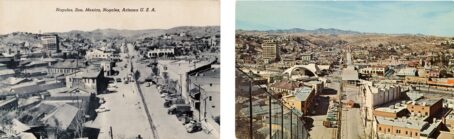

Border fence at Ambos Nogales during the 1940s (left) and during the 1960s (right)

You hear a gun shot being fired in your vicinity. How could this happen? It all feels so absurd, and yet real. In an impulse of survival – like the beetles you used to tease as a kid – you drop to the ground. You expect to feel the bullet entering your flesh, yet the only thing you feel is the pulsating pain in the palms of your hands against the ground and the dust on your sweating face. Whom was that bullet for? You remain motionless, in shock.

You hear the Mexican guards exclaiming in terror believing you are dead, and shortly after a gun fire from the Mexican side. A cry of pain rises from the American side of the border. What follows is a series of excited shouts and gun shootings from both sides of the border. You peek at that dramatic gunfire chaos unfolding, worried to save your skin. The noise is such that you can no longer understand which direction the shots are coming from. Nobody pays attention to you, anymore. In a mix of anger, fear, and commotion, you get up and run as fast as you can, leaving behind your parcel and the raging battle. You have made it in one piece, but your presidente municipal Félix Peñaloza and many other civilian nogalenses will not meet the same fate. In the aftermath of the battle, you would witness the erection of a barrier dividing Ambos Nogales. It would be the first permanent barrier ever erected between Mexico and US.

October 10, 2012

Nogales, Sonora (May 2015). Location where José Antonio Elena Rodríguez was found dead, killed by US Border Patrol agent Lonnie Swartz. He was hit from behind by 10 bullets.

You are José Antonio Elena Rodríguez, a 16-year-old Mexican teenager living in Nogales, Sonora. Everybody at home calls you Tonito. Like other kids your age, you are filled with passion for life and love; your family and friends describe you as kind-hearted and responsible. You like cloudy days, chocolate cookies, and you enjoy spending time with your sisters.

It is 11:30 PM, and you are walking all alone on the sidewalk along the Calle Internacional, the main road that runs parallel to the US-Mexico border fence. You have been playing basketball with your friends till late. You feel tired and hungry, and you are just a few blocks away from home.

Nogales, Sonora (May 2015). School with basketball field along the Calle Internacional, not far from where José Antonio was killed.

You are absorbed in your thoughts when you see a few individuals throwing rocks towards the other side of the border covering the escape of two men who have just climbed over the border fence back into Mexico. Everybody swiftly disappears in the dark. Drug smugglers, likely. It is dark, you could not clearly distinguish their aspect, but you distinctly hear the US Border Patrol guards on the other side, running against the fence and shouting at them. You mind your business and keep walking past that scene, when you are suddenly reached by three bullets at your back in rapid sequence. The pain is excruciating, you do not have time to understand what is really happening. You quickly lose consciousness and pass away.

Nogales, Arizona (August 2023). Flowers left at the border fence not far from where US Border Patrol agent Lonnie Swatz fired his lethal gunshots.

Once, when you were talking with your grandma about your plans, you announced: “Abuelita, I want to be a soldier.” So she asked you: “Why do you want to be a soldier, mijito?” “Why don’t you like soldiers?” you replied. “Well, I don’t like them because they are trained to kill,” she affirmed. You looked at her in the eyes and said, “Abuelita, not all of them are like that. Not all of them are bad. There are good ones. I’ve got friends who are soldiers.” “Being a soldier turns you bad,” she sentenced. So you reassured her: “Not me, abuelita. Nothing is going to turn me bad.”

Nicola Moscelli (Taranto, 1980) is a photographer and documentarist based in the Netherlands and Italy. Using his own photographs as well as archival material, he creates visual narratives focused on the environment from an anthropological perspective, with the aim of analyzing its identity, historical and cultural legacies. His works have been published on platforms such as Urbanautica, Der Greif (Guest-Room curated by Christof Wiesner & Aurélien Valette), Fotograf Magazine, Discorsi Fotografici, and C41 Magazine. ‘Dead End’ is his first long-term visual project, soon to be published as a book by Penisola Edizioni.

Nicola Moscelli (Taranto, 1980) is a photographer and documentarist based in the Netherlands and Italy. Using his own photographs as well as archival material, he creates visual narratives focused on the environment from an anthropological perspective, with the aim of analyzing its identity, historical and cultural legacies. His works have been published on platforms such as Urbanautica, Der Greif (Guest-Room curated by Christof Wiesner & Aurélien Valette), Fotograf Magazine, Discorsi Fotografici, and C41 Magazine. ‘Dead End’ is his first long-term visual project, soon to be published as a book by Penisola Edizioni.