1790, Philadelphia. In the temporary capital of the United States, President George Washington must make an important decision. The War of Independence has been over for several years, and the new Constitution requires the government to establish a federal territory for the nation’s capital. But representatives from the north and the south have been bickering for years about the precise location; both sides want the new capital in their vicinity. His fellow-Founding Fathers Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton manage to compromise: the federal enclave and the new capital should arise somewhere on the border between north and south. It’s now up to George Washington to decide exactly where.

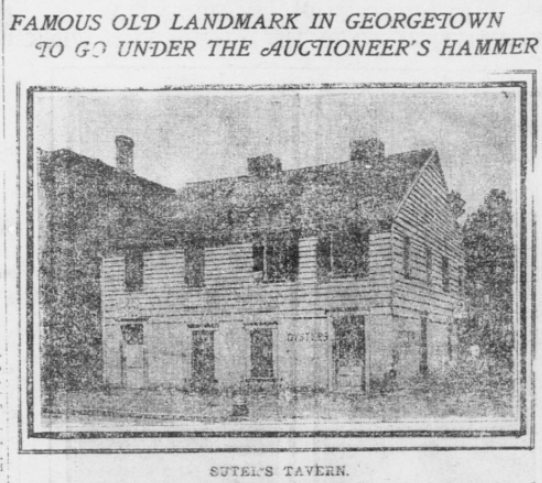

Suter’s Inn, where Washington and L’Enfant met to plan the new capital city

Over drinks in a tavern in Georgetown, he convinced local officials and landowners from Maryland and Virginia to cede or sell land to the federal government, so the new capital could be built on the riverbank of the Potomac River, strategically close to the important port city of Georgetown. Although parts of the area were prone to flooding, it’s an urban myth that Washington DC was built on a swamp (no matter how badly some people today still wish to drain it).

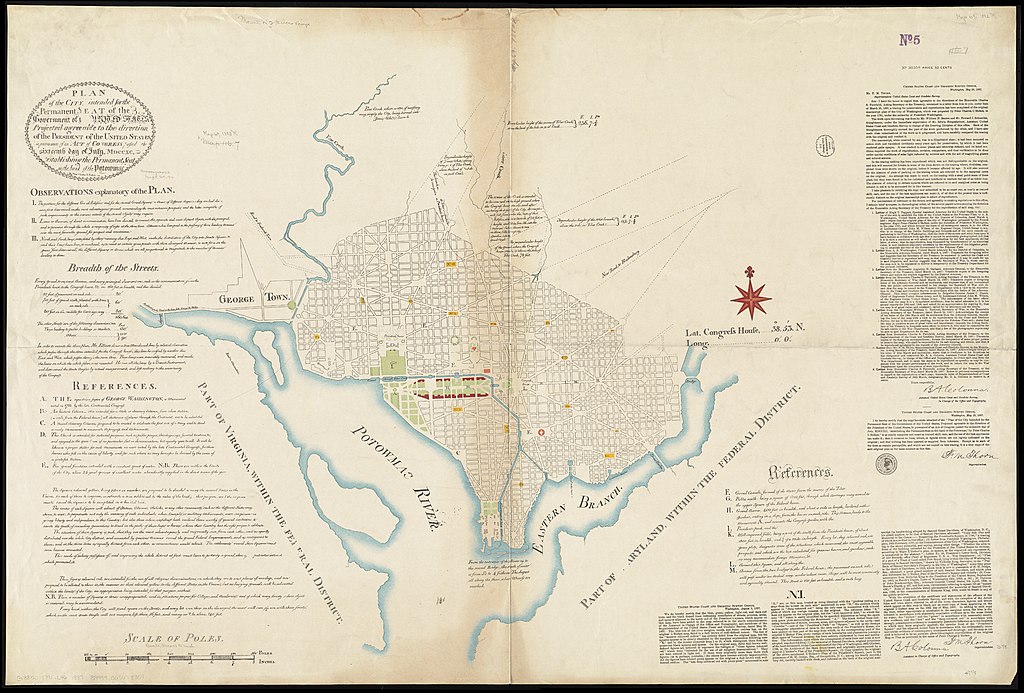

After the District’s borders were determined, Pierre Charles L’Enfant, a French engineer, architect and city planner who also served in the Continental Army during the American Revolution, set to work. His design envisioned a grand capital with monumental buildings and majestic boulevards, with the US Capitol Building and the President’s House (not yet called the White House) as its center points.

Pierre L’Enfant

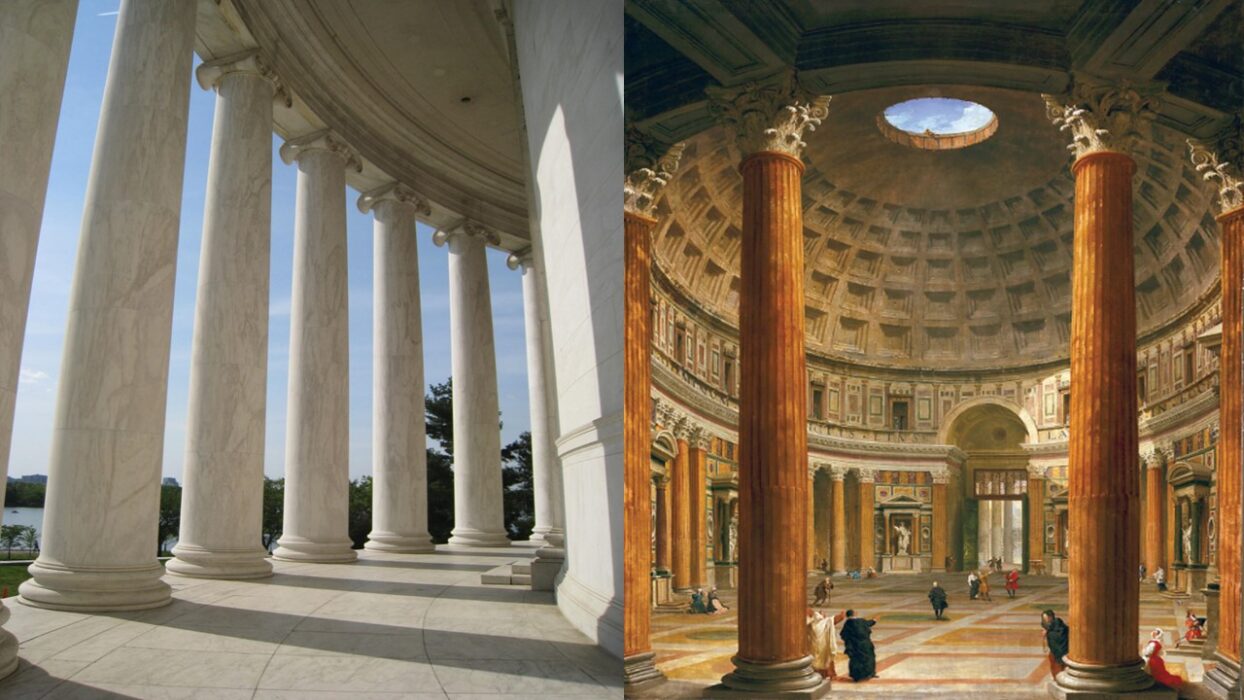

His work was heavily influenced by the Classical Revival or Neoclassical style, which took its inspiration from ancient Roman and Greek architecture. The same thing was happening in Europe. By adopting the same style, L’Enfant wanted to compete with the great European capitals. But the extent to which he implemented the ancients into his design for DC, conveyed something grander than just competition: he was creating the identity of a new nation.

The somewhat romanticized notion of the ancient Greek civilization as the cradle of true democracy is not as strong these days as it was in the past. But in L’Enfant’s era, this was a widely held belief. With his abundant use of classically inspired architecture, L’Enfant tried to give physical shape to the democratic ideals on which the United States was founded. But beside Greek influences, we also find Roman-inspired buildings and monuments, and even Egyptian ones, a trend that continued long after L’Enfant disappeared from view. The message seems pretty obvious: this new nation not only wanted to compete with Europe, but longed to be as great as the great civilizations from the ancient past.

View of Washington (1798)

As time went by, other and more modern architectural styles came to Washington DC. Still, the magnificence of the great empires keeps pulling; in 2020, an Executive Order by former President Trump made classical architecture the preferred style for all future federal buildings in the District.

Next week: Architecture of power. In part 2 of this blog series, we’ll analyze the US Capitol.

Mieke Bleeker works as event coordinator at the John Adams Institute. She holds a Master of Arts degree from the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, where she studied Ancient History. Her fascination for the history and politics of the United States inspires her to visit the country regularly. She has written other blog series for the John Adams, about John Brown’s attack on Harpers Ferry, and about the Pilgrim Fathers.