Conventional wisdom prescribes that the first eighty-five years of American history took place in phases: Phase 1, white male harmony and heroism during the founding and federalist periods; Phase 2, the growth and spread of slavery and disruption of the founding harmony; and Phase 3, disunion sparking the Civil War, followed by the restoration of the nation and the abolition of slavery.

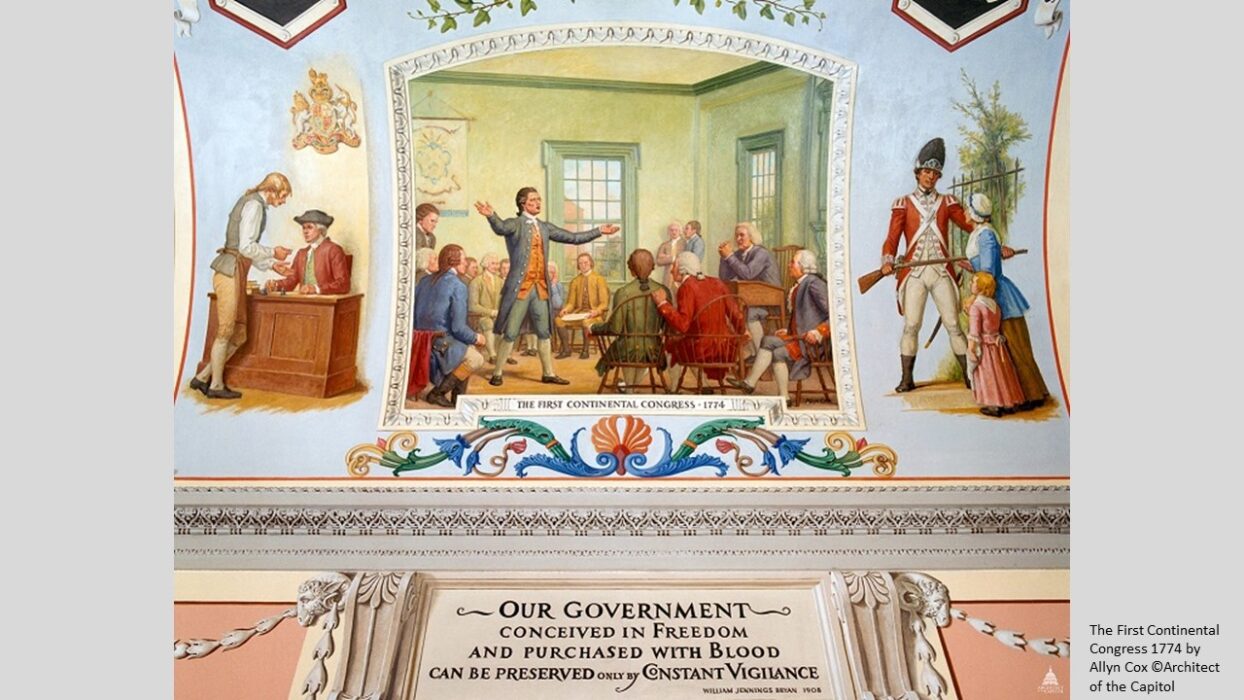

These neat phases of our history are part fact and part fiction. What’s fiction, as my book Disunion Among Ourselves: The Perilous Politics of the American Revolution reveals, is the portrayal of Phase 1 as a honeymoon period that deserves to be set apart from later times of trouble. In fact, from the start, American political leaders feared that without expert statesmanship and stewardship within the Continental Congress the American experiment would plunge into disunion and civil wars.

These neat phases of our history are part fact and part fiction. What’s fiction, as my book Disunion Among Ourselves: The Perilous Politics of the American Revolution reveals, is the portrayal of Phase 1 as a honeymoon period that deserves to be set apart from later times of trouble. In fact, from the start, American political leaders feared that without expert statesmanship and stewardship within the Continental Congress the American experiment would plunge into disunion and civil wars.

No leader better exemplifies this conviction than John Adams in the 1770s. Notably, what worried Adams most was the regional and ideological incompatibilities of the thirteen colonies. In a private letter to a close confidante in Massachusetts, Joseph Hawley, Adams declared in 1775 that the separate American regions were so different from one another as to constitute “several distinct nations almost.”

In saying this, Adams was chiefly referring to the contrasts between republican New Englanders and his “Southern Brethren,” as he sometimes referred to them. Viewing these differences as a tinderbox ripe to ignite, the Massachussian argued that the only way to keep the colonies united and safe was to proceed politically down the pathway of forbearance and compromise.

In the letter to Hawley, Adams drew sharp attention especially to three troublesome North/South lines of demarcation. They were Southern slavery, Southern class stratification, and the hauteur of the planter. In Philadelphia, listening to and watching incessant clashes of interest in Congress, he came to the forlorn conclusion that if the American union of North and South was not handled with care, it would all come apart:

“Gentlemen in the other colonies have large plantations of slaves, and the common people among them are very ignorant and very poor. These gentlemen are accustomed, habituated to higher notions of themselves and the distinction between them and the common people than we are. . . . I dread the consequences of this dissimilitude of character, and without the utmost caution on both sides, and the most considerate forbearance with one another and prudent condescension on both sides, they will certainly be fatal.”

Remarkably, Adams did not highlight other delegates as prime examples of the combustible parochialism and self-superiority that he worried might undermine the American Union. Instead he pointed a finger at himself, confessing in his private diary during the First Congress that he himself embodied the worst of destructive New England chauvinism.

In the diary entry, penned one October day in 1774, he admitted that he was entirely convinced that the people of Massachusetts and the three other New England colonies were superior in most every regard to those from the other nine colonies. “The morals of our people are much better,” he said. “Their manners are more polite and agreeable—they are purer English. Our language is better, our persons are handsomer, our spirit is greater, our laws are wiser, our religion is superior, our education is better.”

During the Second Congress, Adams shared the same sentiments with his wife Abigail by letter, acknowledging the existence within himself of an “overweening prejudice in favour of New England.” Then, looking in the mirror, the founder suddenly asserted that these self-righteous beliefs within himself were an “infirmity, in my own heart” that he must overcome in order to serve as a leader of the dissimilar states.

Adams attributed these prejudices within himself, as well as those gripping the other delegates in Congress, including the Southern delegates’ deplorable attachment to slavery, to the effect on the mind of “Mothers Milk,” by which he meant familiar and cultural childhood learnings instilled from birth.

In Adams’s political psychology, the prejudices lawmakers inherit from their parents and home communities were the worst poisons of politics—and the greatest perils to the incipient United States of America. Especially when culturally and economically distinct peoples attempt to unite in a cooperative enterprise, he believed, the only way out of conflict and paralysis was transcendence of righteousness, leading to sacrifice of interest in hard-fought compromise.

Elsewhere, Adams elaborated on the political science of a successful and safe constitutional republic, opening a window onto what he believed was one of the signature secrets of leadership. “The first virtue of a politician is patience,” Adams once said, “the second is patience; and the third is patience.”

Thus it was not white male harmony and heroism during the founding and federalist eras that kept the American Union safe from disunion and civil wars. Rather, it was extraordinary statesmanship grounded in civic virtues like patience, forbearance, and transcendence of partisan righteousness to embrace compromise. These are the facts of the first quarter century of American history. Portrayal of the founders as a jolly band of brothers is pure fiction.

The Founding Fathers, by John Trumbull

Eli Merritt is a political historian at Vanderbilt University who specializes in the founding era of the United States, the ethics of democracy, and the intersection of demagogues and democracy. He is the author of ‘Disunion Among Ourselves: The Perilous Politics of the American Revolution’. He is also the editor of ‘The Curse of Demagogues: Lessons Learned from the Presidency of Donald J. Trump’ and ‘How to Save Democracy: Inspiration and Advice from 95 World Leaders‘. His articles have appeared in the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, and Chicago Tribune, among other outlets, and he writes American Commonwealth, a Substack newsletter that explores the origins of the United States’ political discontents and solutions to them. Sign up for American Commonwealth.

Eli Merritt is a political historian at Vanderbilt University who specializes in the founding era of the United States, the ethics of democracy, and the intersection of demagogues and democracy. He is the author of ‘Disunion Among Ourselves: The Perilous Politics of the American Revolution’. He is also the editor of ‘The Curse of Demagogues: Lessons Learned from the Presidency of Donald J. Trump’ and ‘How to Save Democracy: Inspiration and Advice from 95 World Leaders‘. His articles have appeared in the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, and Chicago Tribune, among other outlets, and he writes American Commonwealth, a Substack newsletter that explores the origins of the United States’ political discontents and solutions to them. Sign up for American Commonwealth.