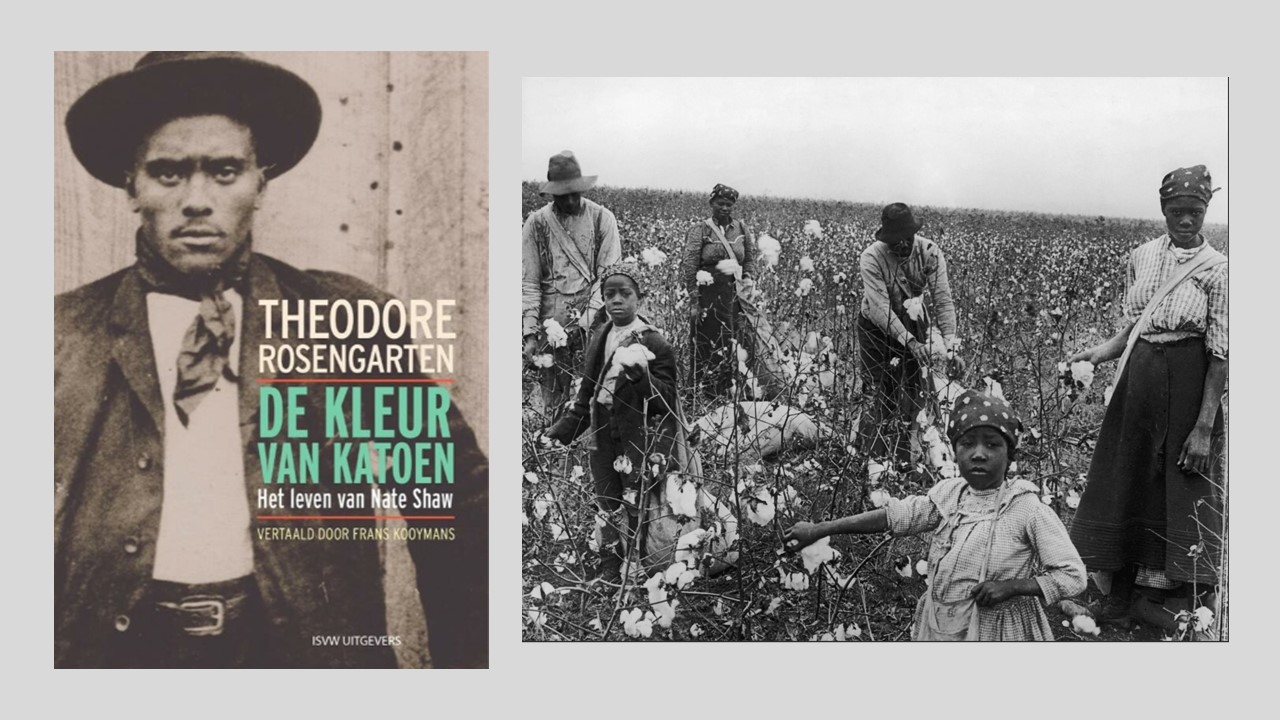

In the spring of 1975, while visiting a bookstore in Miami, I found myself drawn to the self-assured look of a Black man on the cover of a book entitled All God’s Dangers. I bought the book and over the next couple of weeks I was struck by the narrator’s unique language and the succession of his stories. They comprised the rich and compelling life of Nate Shaw, an eighty-four-year-old illiterate but highly intelligent cotton farmer blessed with an astounding memory. Recorded and compiled from his oral reminiscences by a young white historian, this plain-spoken but often poetic account of an “over-average man” bears witness to the wrenching changes in the lives of Southern Blacks during the century between the end of Reconstruction in the 1870s and the Civil Rights movement in the 1960s.

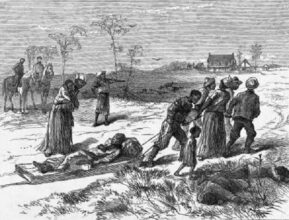

Racial violence during Reconstruction

The book filled a gap, then and now, in African American history, and, I dare say, in world literature. With the awakening of interest in our own legacy of slavery and colonial history, it strikes me as timely and relevant here too. But there is much more to the book than a searing indictment of racial oppression. Shaw surprises the reader with his literary flair. For example, he finds himself “bursting like a butterbean in the sun” when his landlord tries to get him to sign away his movable property on what was supposed to be a lien on his cotton. In one encounter after another he displays the skills of a classic storyteller in his use of mimicry, copying the accents, gestures, mannerisms, and speech patterns of both friend and foe. A New York Times reviewer called him a Black Homer, recounting his Alabama Odyssey with awesome power and passion.

When I first read the book, white supremacy was riding high. Now, half a century later, it has re-emerged in the states that lost the Civil War in the form of a right-wing campaign to water down the country’s racial history, diminish reporting on the lasting impacts of slavery in public and private life, and minimize the life stories of individuals who devoted themselves to overturning “this southern way of life.” Nate Shaw was, indeed, a freedom fighter, and he not only lived to tell the tale, but to tell it with gusto. His story sings of life’s pleasures, of the rhythm of the seasons, of honest work, and of the stubborn persistence of hope when it might have vanished.

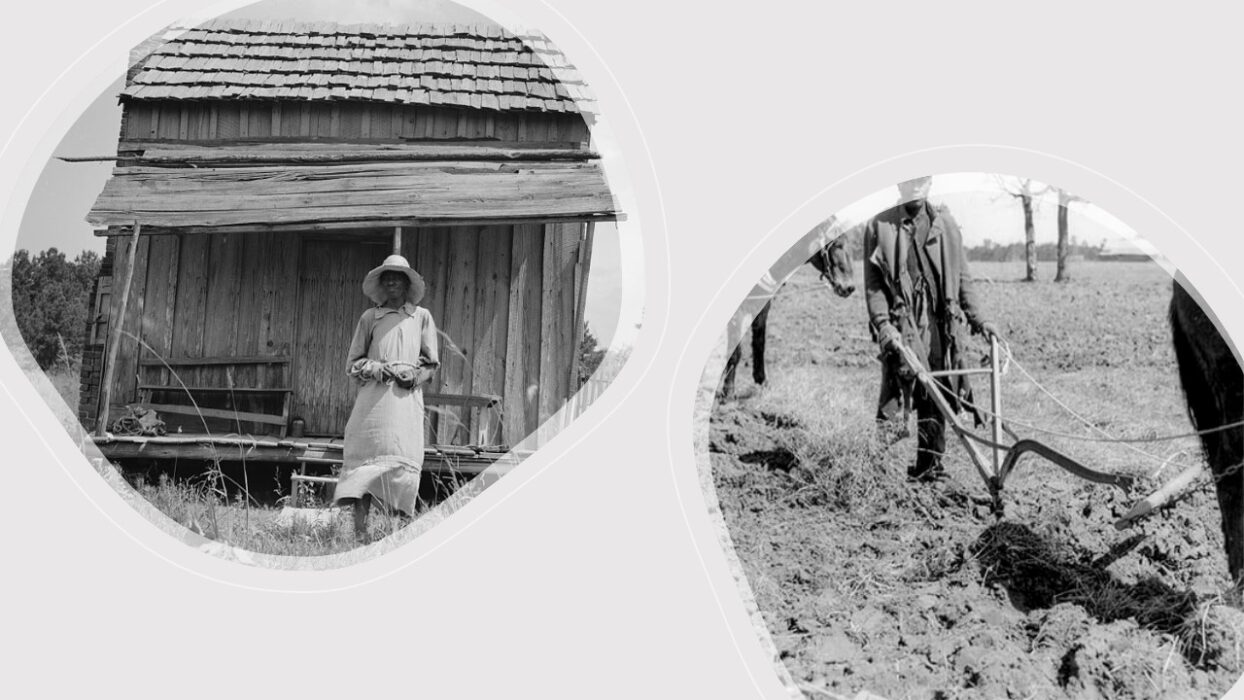

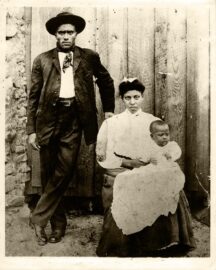

Nate Shaw and his family

It may be tempting to regard his life, which ended in poverty, as a failure. But that would be incorrect. Put to plowing behind a mule when he was only nine, Shaw would escape his father’s domination and rise, despite setbacks, from hired hand to sharecropper to tenant farmer to landowner. He married his first sweetheart and together they raised nine children, all of whom put their shoulders to the wheel. He would come to own fine mules and two automobiles back in 1931, making him an American success story—if only the people who controlled the purse strings would play by the rules. He lost his wealth and almost lost his life, when, for reasons that lay at the heart of the book, he walked headlong into a confrontation with a sheriff’s posse that was about to confiscate a neighbor’s livestock.

All God’s Dangers has been compared to William Faulkner’s trilogy of the Snopes, which sets out the saga of a white tenant farm family in Mississippi. Shaw’s life stories reflect a similar idiom and the same wry humor but they are grounded more firmly in the process of making a cotton crop, season after season, fighting off the chains of indebtedness. This is what Studs Terkel, the eminent chronicler of oral histories, means when he calls Shaw’s tale “an anthem to human endurance.”

Yes, it takes some endurance to go through the book, for it meanders like the windings and convolutions of Sitimachas Creek, which is true to the method and settings of the recordings. Reviewing the book anew in 2014, in the midst of the Black Lives Matter movement, forty years after its original publication, the Times critic exclaimed, “it reads as if [Black singer and guitarist] Huddie Ledbetter spoke it while W.E.B. Du Bois took dictation.”

Black Lives Matter mural

The life of Nate Shaw seemed to me to have such close parallels with the lives of many individuals in Surinam and the Dutch Antilles that his narrative was waiting for a translation. Rendering the vernacular of an unlettered Black farmer from the American South while preserving its original meaning, connotation and style, and justifying the high bar set by the praise the book has received, was the challenge I undertook in De kleur van katoen.

Next week, we go back to 1619 and examine a new view on American history.

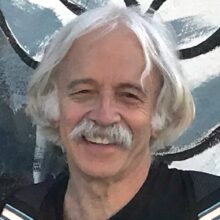

Theodore Rosengarten is a writer, teacher, and social activist from McClellanville, South Carolina. Born in Brooklyn, New York, Ted earned his bachelor’s degree from Amherst College and his PhD in The History of American Civilization from Harvard University. Even as a child, he was obsessed by the Black struggle for justice and freedom and by the Nazi’s destruction of the Jews in Europe. His first book, ‘All God’s Dangers: The Life of Nate Shaw’, the oral history of a Black tenant farmer from Alabama, won the National Book Award for Contemporary Affairs in 1975. Last year, Yad Vashem Studies published Ted’s critical review of Steven T. Katz’s mammoth new volume, ‘The Holocaust and New World Slavery’.

Theodore Rosengarten is a writer, teacher, and social activist from McClellanville, South Carolina. Born in Brooklyn, New York, Ted earned his bachelor’s degree from Amherst College and his PhD in The History of American Civilization from Harvard University. Even as a child, he was obsessed by the Black struggle for justice and freedom and by the Nazi’s destruction of the Jews in Europe. His first book, ‘All God’s Dangers: The Life of Nate Shaw’, the oral history of a Black tenant farmer from Alabama, won the National Book Award for Contemporary Affairs in 1975. Last year, Yad Vashem Studies published Ted’s critical review of Steven T. Katz’s mammoth new volume, ‘The Holocaust and New World Slavery’.

Frans Kooymans, translator of Dutch to English and vice versa, has an American background. He emigrated in his early teens and lived in Ohio and northern Florida, where he encountered a society still marked by racial segregation. He spent five years in a seminary, taught Latin, then switched to become an accountant in Miami. Upon returning to the Netherlands, he continued in accounting and finance. A major company reorganization led him into his current profession. He calls the translation of Rosengarten’s ‘All God’s Dangers’ into ‘De kleur van katoen‘ his “covid project”.

Frans Kooymans, translator of Dutch to English and vice versa, has an American background. He emigrated in his early teens and lived in Ohio and northern Florida, where he encountered a society still marked by racial segregation. He spent five years in a seminary, taught Latin, then switched to become an accountant in Miami. Upon returning to the Netherlands, he continued in accounting and finance. A major company reorganization led him into his current profession. He calls the translation of Rosengarten’s ‘All God’s Dangers’ into ‘De kleur van katoen‘ his “covid project”.