Enlightened Protestants and Catholics both wanted to liberate simple folk from ignorance, fear, and superstition by good instruction. In enlightened eyes, fear of thunderstorms was not only evidence of a wrong understanding of God, but also the chief cause of the origin and spread of all kinds of superstitious ideas and practices.

A particular source of irritation was the old custom of ringing church bells to avert an approaching storm. Since the late Middle Ages the idea gained ground that it was often devils who (with God’s permission) caused a thunderstorm. After all, didn’t they spring from the pit of sulphur beneath the earth, causing explosions in the atmosphere above? The Roman Catholic tradition took over the ancient pagan idea that bad spirits could be repelled and driven out by loud noise, for instance by church bells. Consecrated church bells in particular were considered to possess devil-exorcising powers. Bell-ringers were believed to be the devil’s specific target. For that reason some of them wore sacred clothing: a surplice with a priest’s stole over it. Of course, the real cause of their vulnerability was the rope they held, which was a perfect conductor.

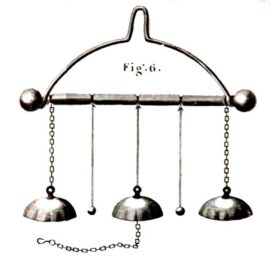

‘Franklin bells’ are an early demonstration of electric charge designed to work with a Leyden jar or a lightning rod.

Enlightened minds abhorred these practices, partly because they preferred to dissociate themselves from what they regarded as magic, but mainly because bell-ringing was simply far too dangerous. Instead, they recommended Benjamin Franklin’s lightning rod. In 1783 – the year of multiple terrible thunderstorms –rulers of numerous European states including Prussia, Austria, and Bavaria, prohibited bell-ringing altogether. France, where nearly a hundred bell-ringers had been killed or injured by lightning in 1783, followed the next year. And Franklin? With a fine sense of irony he attached a set of little bells to the very first lightning rod he installed on his Philadelphia home, which would tinkle whenever a storm approached – a wry nod to the old, but now decried custom of bell-ringing.

Farms and Fires

Farmhouses in this era were usually built mainly of combustible material such as wood and reed. In order to keep the demons that caused lighting at a safe distance, all sorts of objects and tools were placed in and around the farm, such as horseshoes, axes, scythes, sickles, dung forks, even harrows, ideally with their tines upwards. Sometimes the carcasses of vultures, hawks, owls, magpies, crows, or bats might be nailed to the door, preferably with wings outspread. Even a tall oak could act as a natural lightning rod because that tree had been sacred to the god of thunder since time immemorial, whether to the Greek Zeus, Roman Jupiter, or Germanic Donar.

‘Summer’ by Abel Grimmer (1607). A scythe can be seen placed with its sharp edge upwards, possibly to deter demons while a thunderstorm is brewing.

Thunder demons had to be exorcised, by hook or by crook. That is why fires caused by lightning were not to be extinguished not by water, but by “sour” fluids, for instance by the moisture that seeped from the dunghill. In eighteenth century Lüneburg (Germany) vinegar was preferred, a barrel of which was kept on top of every church tower to fight fires resulting from a lightning strike.

Although sober-minded men like Franklin and others had proved that lightning was electrical in character, electricity itself remained a new and mysterious phenomenon. Attempts to describe it almost inevitably ended up in the use of metaphors. In the end, these metaphors proved to be the starting point of the poeticization of electricity, as we shall see in the next part of this blog series ‘Thunderstorms in Art and Literature’.

Jan Wim Buisman (1954) is a retired Lecturer on the History of Christianity, with a special focus on the early modern period. He is now affiliated as guest researcher at the Leiden University Centre for the Study of Religion. He has written extensively on the history of religious mentalities and the impact in the Netherlands of natural disasters on views of God, man, and nature, between 1750 and 1830. Click here to order the book, ‘Lightning in the Age of Benjamin Franklin: Facts and Fictions in Science, Religion and Art’ by author Jan Wim Buisman. Use discount code jai50.

Jan Wim Buisman (1954) is a retired Lecturer on the History of Christianity, with a special focus on the early modern period. He is now affiliated as guest researcher at the Leiden University Centre for the Study of Religion. He has written extensively on the history of religious mentalities and the impact in the Netherlands of natural disasters on views of God, man, and nature, between 1750 and 1830. Click here to order the book, ‘Lightning in the Age of Benjamin Franklin: Facts and Fictions in Science, Religion and Art’ by author Jan Wim Buisman. Use discount code jai50.