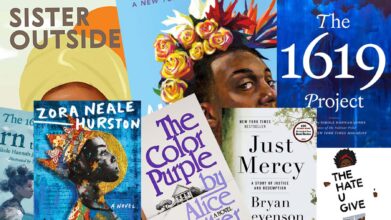

Not only were African people enslaved, their history has been enslaved as well. Books by Black authors that espouse a Black perspective on history and current events are being ferociously targeted for removal from American schools and libraries. Allied with and even led by governors and legislatures in states that in the past resisted integrating public schools, more than fifty organizations and their local chapters are beating the drums of censorship. The most visible and vocal of these, Moms for Liberty, began by campaigning against COVID-19 protection in schools, including mask and vaccine mandates. Following the murder of George Floyd in May 2020, when social justice movements demanded the country face up to the reality of systemic racism, Moms shifted gears and pushed for an end to “liberal indoctrination” in schools, making a public ritual of condemning books they deemed “divisive” and harmful to national unity.

© College_library_ cc-by-2.0

Texas leads in the number of banned books, approaching one thousand, but Florida goes furthest in the rhetoric of banning and threatening teachers who bring up “divisive concepts” in the classroom. A new state law in Florida limits discussion on race and requires teachers to tell students that there were upsides to being enslaved. Another new law, which in its initial form forbade teachers from discussing sexual orientation or gender identity in kindergarten through third grade, has expanded the prohibition through twelfth grade. And still another new law throws a curtain over classroom books in all subjects—the sciences and math as well as literature and social studies—requiring them to undergo sustained review and approval by the governor’s appointees, and carrying fines and felony charges for teachers who violate the guidelines. Parents are empowered to scrutinize video recordings of a child’s class for signs of forbidden material.

Florida has pulled funding from advanced high school courses in African American history. If only the governor had read All God’s Dangers before pulling the plug. He named sixteen African American achievers who allegedly acquired their skills in the school of slavery. At the top of his list was Ned Cobb, the Nate Shaw of All God’s Dangers, identifying Cobb as a blacksmith, which he never was; neither was he ever enslaved. In fact, the governor misidentified all sixteen Black individuals, pleading that the principle he was pushing is more important than the details.

Thus, ideas once accepted by scholarly consensus have fallen to pedagogical violence that aims to appease adults rather than educate children. To say, for example, that after slavery, African Americans continued to endure wealth disparities enforced by racial discrimination would violate state laws because such explanation fails to offer alternative reasons for the wealth gap. To call the destruction of Black communities in central Florida, in Ocoee in 1920 and Rosewood in 1923 massacres, violates a taboo and breaks a law because it promotes CRT—Critical Race Theory—the Satan of lies.

CRT was a legal concept coined in the 1980s that developed into an academic rebuttal to the notion that America is colorblind. CRT holds that anti-Blackness is woven into the social and political fabric of the United States and is not merely a collection of individual prejudices. To the left, CRT is a way of understanding how racism has shaped public policy and social behavior throughout our history. To the right, it’s a divisive discourse that pits people of color against Whites. Florida’s new laws and the national army of book banners aim to root out CRT from lesson plans and library shelves.

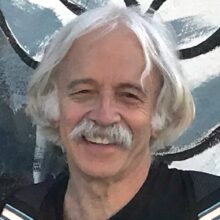

George Wallace blocking the entrance to the University of Alabama, 1963

Keeping Black people in ignorance of their history is as old as slavery. Teaching the message of the gospel and simultaneously instructing the enslaved to obey their masters, missionaries to rice plantations in the Carolina colony in the early 1700s understood that “knowledge is dangerous.” What was the meaning of the Civil War, a hundred and sixty years later, observed educator Booker T. Washington, if not “a whole race trying to go to school?” African Americans were still trying to secure equal educational rights in 1963, when Alabama Governor George Wallace famously stood in the schoolhouse door blocking students from entering the University of Alabama.

Next week more on the books being banned from classrooms and libraries.

Theodore Rosengarten is a writer, teacher, and social activist from McClellanville, South Carolina. Born in Brooklyn, New York, Ted earned his bachelor’s degree from Amherst College and his PhD in The History of American Civilization from Harvard University. Even as a child, he was obsessed by the Black struggle for justice and freedom and by the Nazi’s destruction of the Jews in Europe. His first book, ‘All God’s Dangers: The Life of Nate Shaw’, the oral history of a Black tenant farmer from Alabama, won the National Book Award for Contemporary Affairs in 1975. Last year, Yad Vashem Studies published Ted’s critical review of Steven T. Katz’s mammoth new volume, ‘The Holocaust and New World Slavery’.

Theodore Rosengarten is a writer, teacher, and social activist from McClellanville, South Carolina. Born in Brooklyn, New York, Ted earned his bachelor’s degree from Amherst College and his PhD in The History of American Civilization from Harvard University. Even as a child, he was obsessed by the Black struggle for justice and freedom and by the Nazi’s destruction of the Jews in Europe. His first book, ‘All God’s Dangers: The Life of Nate Shaw’, the oral history of a Black tenant farmer from Alabama, won the National Book Award for Contemporary Affairs in 1975. Last year, Yad Vashem Studies published Ted’s critical review of Steven T. Katz’s mammoth new volume, ‘The Holocaust and New World Slavery’.

Frans Kooymans, translator of Dutch to English and vice versa, has an American background. He emigrated in his early teens and lived in Ohio and northern Florida, where he encountered a society still marked by racial segregation. He spent five years in a seminary, taught Latin, then switched to become an accountant in Miami. Upon returning to the Netherlands, he continued in accounting and finance. A major company reorganization led him into his current profession. He calls the translation of Rosengarten’s ‘All God’s Dangers’ into ‘De kleur van katoen‘ his “covid project”.

Frans Kooymans, translator of Dutch to English and vice versa, has an American background. He emigrated in his early teens and lived in Ohio and northern Florida, where he encountered a society still marked by racial segregation. He spent five years in a seminary, taught Latin, then switched to become an accountant in Miami. Upon returning to the Netherlands, he continued in accounting and finance. A major company reorganization led him into his current profession. He calls the translation of Rosengarten’s ‘All God’s Dangers’ into ‘De kleur van katoen‘ his “covid project”.