As one of the key modernist enemies of the Nazi Party, the selection of Walter Gropius to design the US Embassy in Athens was a pairing of architect with location that was rich with Cold War significance.

In 1919, Gropius founded the Bauhaus, which quickly became an epicenter of the modernist movement in Germany’s Zwischenkriegszeit (the period between World War I and World War II). The institution produced such architects as Marcel Breuer, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and Herbert Bayer. The Bauhaus was forced to disband by the Nazis in 1933, and Gropius emigrated to the United States. As an American emigree, Gropius was at the center of the great period of collaboration happening between displaced European modernists and American architects during the war. In 1938, he was appointed chair of the Department of Architecture at Harvard University, and designed such buildings as the Harvard Graduate Center and the Pan Am Building (now Met Life) in New York City.

As the Cold War battle between democracy and communism played out in art and architecture, the project to build a new US embassy in the symbolic “cradle” of democracy was of the highest importance. In 1954, congressional pressure was mounting against the modernist embassy program. Bowing to that pressure, FBO had agreed to hire what Congressman John Rooney called “high-class” American architects for future Embassy projects. Rooney failed to specify that such architects should be American-born, and to the consternation of himself and other congressional conservatives, FBO hired many of the prominent European architects who had emigrated to the US and become citizens during the war—Gropius among them.

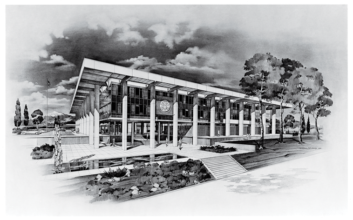

A Gropius-designed architectural rendering submitted for review

Given how conspicuously Hitler had suppressed Gropius in Germany, his selection for the Athens Embassy project was a symbolically powerful choice on the part of the State Department. In the birthplace of western democracy, the US built an architectural embodiment of its democratic ideals designed by an architect who had risked much for the sake of the democratic ideal of freedom of expression. The US Embassy in Athens proved to be one of the most successful projects of the State Department’s modernist embassy program.

Gropius presented his design to the US State Department’s Architectural Advisory Committee in 1957. The embassy was a perfect square, surrounding a central courtyard with a fountain. The glass-enclosed offices hang from a system of structural columns clad in the same Pentelic marble as the Parthenon, and blue ceramic sun screens at ground level, wide overhangs around the perimeter of the patio, and a continuous slot to allow hot air to escape from under the overhangs all help to contribute to a natural climate control system for the building.

Gropius (left) on site upon completion of the building

Gropius’ design was a major critical success. Architectural Forum described Gropius as “one of modern architecture’s Olympian figures” and his design as “a modern bow to the classical ideal,” writing : “On a sloping site about a mile from the Parthenon stands the new U.S. Embassy. It is a symbol of one relatively young democracy at the fountainhead of many old democratic and architectural traditions.”

The praise of the architectural community was echoed in the popular press. In 1957 and 1958, the Boston Globe dedicated two articles to the embassy. In 1961, the New York Times praised Gropius’ design in two separate articles. In publications ranging from The Washington Post to Time magazine to the Christian Science Monitor, Gropius’ embassy was hailed as a modern masterpiece. Gropius’ building was widely admired by contemporary architects, and it inspired such subsequent designs as Oscar Niemeyer’s Palácio de Planalto in Brasilia (1958).

The embassy in its dense urban context in central Athens

The Bureau of Overseas Building Operations (the current incarnation of the Foreign Buildings Office) describes Gropius’ Embassy as: “… a metaphor for democracy in the country to which democracy owes so much.” The building still functions as an embassy today and is currently being retrofitted to meet 21st-century security needs. The embassy is a designated landmark and was listed on the Secretary of State’s Register of Culturally Significant Property in 2006.

David B. Peterson is CEO of Onera Group, Inc. and Executive Director of the Onera Foundation, a private foundation dedicated to supporting historic preservation. Mr. Peterson is Board Chair of the Harlem Academy school, an independent school offering students a leading education regardless of economic circumstance. He serves on the Advisory Council of the Glass House, a National Trust Historic site. He holds a BA from Dartmouth College, an MBA from NYU, and a MS in Historic Preservation from the Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation. Click here to order ‘US Embassies of the Cold War’.

David B. Peterson is CEO of Onera Group, Inc. and Executive Director of the Onera Foundation, a private foundation dedicated to supporting historic preservation. Mr. Peterson is Board Chair of the Harlem Academy school, an independent school offering students a leading education regardless of economic circumstance. He serves on the Advisory Council of the Glass House, a National Trust Historic site. He holds a BA from Dartmouth College, an MBA from NYU, and a MS in Historic Preservation from the Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation. Click here to order ‘US Embassies of the Cold War’.