Paradoxes of War

December 27, 2015

According to Freud if we keep track of our dreams over time eventually a pattern emerges that tells us important truths about ourselves. The same may be true about the conscious stories we tell repeatedly about ourselves to ourselves and to others. Since serving in Viet Nam as an artillery officer I have told a number of stories about my experience there. I never thought much about any pattern that emerged from these stories that have rattled around in my memory for the past forty-five years until my anxiety about writing them for this collection provoked a particularly violent dream one night from which I awoke with the outline for this essay full blown in my head. Here are two of those stories.

At the right is McGrath.

One night during the 1968 Tet offensive Viet Cong sappers blew up piles of ammunition at the Long Binh, the largest U.S. supply depot in Viet Nam. One of the sappers caught, rumor has it, worked at the Long Binh officer’s club as a barber. Daily he had a razor to the throats of generals. That we hired to work in our base camps during the day the people we fought against at night was one of the strange features of this war. It also may be why Viet Cong intelligence often was better than U.S. military intelligence.

Another night I was the OIC of one of the sectors of the perimeter guard at Bear Cat, where my unit was stationed. Between the perimeter berm and the jungle was a cleared area of more than a hundred yards planted with mines and barbed wire. At one point in the early morning hours we heard an explosion in one of the adjacent sectors followed by rifle, machine gun, and grenades coming from our perimeter guards. Within minutes artillery began dropping into the area of the initial explosion; then helicopters and an AC-47 gunship poured fire into the area. Before the incident was over B52 bombers diverted from targets in North Viet Nam dropped their thunderous loads in the jungle just beyond the cleared area. Then all was quiet. When dawn broke a patrol went out to investigate. All they found in the area of the initial explosion was a well-mutilated monkey. Apparently the initial explosion came from the grenade launcher of one of our own soldiers who had fired without permission at a sound he heard in the open area.

During my tour in Viet Nam I saw no indication whatsoever of any kind of progress, military or political. In fact, we devastated the country and impeded its progress into the modern world for more than a decade.

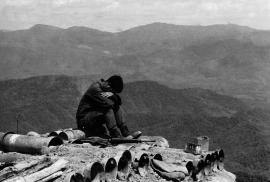

A South Vietnamese soldier rests his eyes at a lonely outpost northeast of Kontum, 1974 (AP Photo/Nick Ut).

In my research as an English professor I read an enlightening essay by British film scholar John Hill, who points out that in most American films violence typically is the solution to social and personal problems, while in British and European films violence is usually the problem that destroys societies, families, and individuals.1 (James Bond films muddy his thesis a bit, but one could argue that Hollywood is as much responsible for James Bond as the British.) We still live in a culture where World War II, with its clear sense of accomplishment and its clear division between the good guys and the bad guys, constructs our paradigm for war, a war made for Hollywood and John Wayne. This paradigm has been reproduced by Hollywood over and over, not only in war films but also in westerns and in the action films that have replaced them, where the solitary hero who lives on the edge of normal society preserves that society through acts of violence.

All the wars since World War II–Korea, Viet Nam, Iraq, Afghanistan—have not shaken the Hollywood paradigm. To be sure, there have been some counter narratives, but the Hollywood paradigm still persists; the dream factory rolls out one violent solution after another. Europeans, who have experienced the destruction of modern warfare, are much more reluctant to go to war than Americans, who have been fortunate that no modern war has been conducted on their own territory. Perhaps that is why we can still conceive of violence as the solution to problems rather than the problem to be solved.

1. John Hill, “Images of Violence,” Cinema and Ireland eds. Kevin Rockett, Luke Gibbons and John Hill, (London: Routledge, 1988), 147-193.

This is the last post in our blog series ‘The War We Would Forget’. Also read JAI director Tracy Metz’s introduction (December 2), editor Phillip C. Schaefer’s introduction (December 4), the essay by veteran Jim Harris (December 7), the essay by veteran Glen Kendall (December 9), the essay by Karl F. Winkler (December 14), the essay by George J. Fesus (December 16), the essay by veteran Carl DuRei (December 18), the essay by James Laughlin (December 21), and the essay by John T. Lane (December 23).