During the Second World War, a Dutch-Jewish family had to go into hiding to avoid deportation to Germany. When the war was over, they emigrated to the United States. Almost eighty years later, they remain in contact with the Dutch families that helped them survive. Eline Hopperus Buma reveals how the war created a tale of intertwined family histories spanning three generations.

“I have no recollection of those years in Diepenveen,” Otto Verdoner tells me when we first meet in Spring 2010 at Denver International Airport. He is seventy-one, but I recognize him straightaway from the photographs. On the way to his home in Boulder, I recount some of my father’s stories from the war. It turns out that Otto in fact remembers a good deal from the war. He begins to fill in details and adds other stories, new to me, but later confirmed by my father Wiete, his ‘brother-in-hiding’. Once in Boulder he introduces me to his wife Daisy and his youngest son David, who is in his early twenties. David doesn’t speak Dutch and doesn’t really know who I am. I tell him that he and I would not be talking to each other now in Boulder if his father, a Jewish boy in hiding in my grandparents’ house, had been found out. If that had happened both his father and mine would most likely not have survived the war. Then it dawns on him how our lives are connected. But did the war affect him personally? Do the children and grandchildren of the Verdoner family feel ‘Dutch’, even if only partially? Are they interested in what happened to their family during the war? Do they know the full story?

The Bicycle Factory

In 1909 Abraham Verdoner and Leman Velleman went into business together, initially selling bicycles imported from England. After some years the firm focused on the production of bicycles instead. In 1932 Abraham and Leman moved their bicycle factory, named De Magneet, to Weesp, just south of Amsterdam, and shortly afterwards Gerrit Verdoner succeeded his father as director and co-owner. He married Hilde Sluizer in 1933 and the couple subsequently moved into a villa on the tree-lined Trompenbergerweg in Hilversum where their three children were born. Gerrit used a Buick for his daily commute to the factory.

The Second World War upset the family’s comfortable life. The German occupiers outlawed Jewish ownership of firms, forcing Gerrit to transfer control over the factory to his trusted co-director, who had been in the business for many years. The local authorities took pride in their town becoming Judenrein (free of Jews) and ordered all Hilversum Jews to depart. Gerrit and Hilde decided that for their safety the children had to go into hiding in separate places, while they themselves moved in with Gerrit’s parents in Amsterdam. When Hilde purchased a false id from an imposter, she was arrested and detained at an Amsterdam police station. In December 1942 she was deported to Westerbork where she was confined for many months. For some time she was able to send letters to her husband.

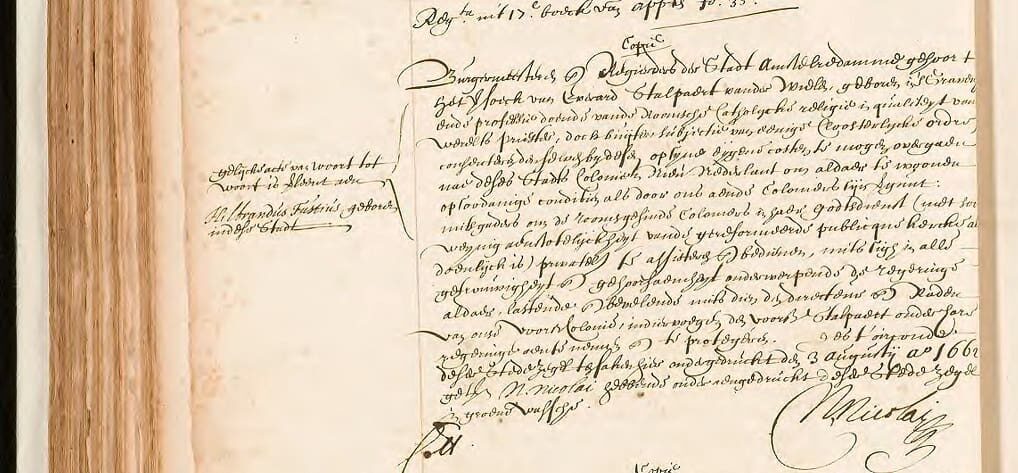

Declaration to lift freezing of Gerrit Verdoner’s assets (1946)

Gerrit Verdoner went into hiding in September 1943. When the war came to an end, he kept up hopes for his wife’s return. He gathered together his children from their places of hiding and returned to their house in Hilversum, where he tried to rebuild his family’s life as well as he could. After a few months, Gerrit received news that his wife, together with his parents, had been put on transport from Westerbork on 8 February 1944. They were gassed upon arrival in Auschwitz, three days later.

Blow upon Blow

In these trying times, Gerrit had to face another issue as well. The ‘trusted’ co-director had not expected Verdoner to survive the war and return to reclaim ownership of his share in the bicyle factory. In fact, he had usurped the company and, adding insult to injury, even appropriated Gerrit’s Buick for his own use. Fierce and exhausting litigation ensued, with parties accusing each other of collaboration with the German occupiers. While investigations were carried out by the Dutch authorities, both men were incarcerated. Gerrit’s business assets were temporarily frozen, as they might be subject to confiscation. For a few months, the three children returned to the families that had hidden them during the occupation, upsetting Gerrit’s attempts to rebuild family ties and putting even more pressure on him. It took over a year to resolve all the legal issues, but in November 1946 Gerrit was finally acquited and the financial issues resolved. By this time, he had decided to leave the Netherlands and follow family members, who had made the trip to the United States. Gerrit sought a better future for himself and for his children across the Atlantic Ocean. Yet the accumulated grief and anxiety had taken its toll on his health.

In early December 1946, the ship Gripsholm sailed for America. Gerrit Verdoner was a keen cinematographer and had captured many pre-war family moments in Hilversum on celluloid. During the voyage he used his film camera to record his children running on the ship’s deck, on their way to America. Gerrit continued filming after the arrival in New York and his home movies include his sister Jo and her husband Barend Broekman, walking on Fifth Avenue, with the Metropolitan Museum in the background, as well as Gerrit’s second sister Jacqueline (Lien) and her husband Ben Stibbe. The children were looking forward to meeting their uncle Kurt, Hilde Verdoner’s brother who had emigrated to the U.S. before the war. Her other brother, Otto, died in Bergen-Belsen. The people in Gerrit’s home movies are well-off and outwardly happy, perhaps imbued by the optimism of the post-war years. Yet within a few months after the family’s arrival in America, Gerrit Verdoner fell ill. He died of cancer in October 1947. Yoka (born in 1934), Fransje (1937) and Otto (1939) were now orphans.

Still from the video Gerrit Verdoner shot during his family’s voyage to New York (1946)

Time to Hide

When Hilde and Gerrit arranged for their children to go into hiding, they found Yoka a new home in Woubrugge, with burgomaster Dirk Rijnders and his wife Ella Rijnders-Van Kempen. During the war years their daughter Roosje was born. Yoka and Roosje remained good friends until Roosje’s early demise. Fransje went to Zandvoort and subsequently to the Plantage Middenlaan in Amsterdam, where she lived with her foster parents near the Artis Zoo.

Otto was lodged with my grandparents in Diepenveen. It is not clear how the contact was established. It may have been through the family of my grandmother, Mia Hopperus Buma-Van Hall, as her brothers, Gijs and Wally van Hall, were deeply involved in the Dutch resistance. Alternatively, connections of my grandfather, Wiete Hopperus Buma, director of a bank, may have played a role. Often security concerns necessitated the use of anonymous intermediaries. My grandmother didn’t know and my grandfather, the only person who might have shed some light, died in 1961.

Through the Window

Otto often built towers of wooden blocks in the sandbox in the garden, together with my father, who was thirteen years his senior. They loved to hang a small Swiss cowbell in the top of the tower. One morning Otje, as he was called, was playing in the garden when he noticed two German soldiers on the patio. They offered him a cookie, which he accepted. My grandmother summoned him to the kitchen and explained that the two billeted soldiers were now staying in my grandfather’s study, as he often was away for work. She told Otje to stay well away from the soldiers and he did not dare confess that he had already accepted a cookie! My grandmother managed to convince the soldiers not to use the front door, because of the large number of children in the house, including Otje. In a small act of resistance, she asked the soldiers enter and exit the house through a window, which they consented to do. The daily clambering provided a spectacle which my grandmother secretly enjoyed.

The house in Diepenveen where Otto went into hiding

When the war was over, Gerrit Verdoner visited Diepenveen to pick up his son. Otto did not initially recognize his father, so Gerrit stayed for a week to give them both time to get accustomed to each other again. It worked: Otto took his father’s hand and dragged him through the village, introducing him to everyone. Then it was time to say goodbye and take a taxi to Hilversum, together with his father. Otto would keep in contact with his foster family, in particular with his foster-mother Mia. In 1998 Otto made a trip back to the Netherlands. Together with members of his foster family he visited the house in Diepenveen, where he had lived decades earlier.

He also went to the Westerbork transit camp, including the National Westerbork Memorial, consisting of 102,000 stones. Each stone represented a single person who had stayed at Westerbork and was deported to Nazi extermination camps. Otto aimed to reconnect to the spirit of his mother, but the visit did not achieve the desired result. He is still seeking answers and, in his own words, compares himself to “a child in a supermarket, crying for his lost mother.” Coming to terms with the sense of loss from his early years is a process that continues unabated. Perusing family documents, painful though the details may be, provide some comfort and further the process.

War Stories

As a young child I often stayed with my grandmother in Diepenveen. She told me about the war years and showed me the places in the house where history became palpable, such as the crawl spaces between floors, where my father and uncle often had to hide to avoid being unvoluntarily recruited for the Arbeitseinsatz, i.e. forced labour in German factories. She also pointed out the note that Otje scrawled on the wall next to the stairs leading to the attic, where he kept his Dinky Toys car collection. What my grandmother told me left a deep impression. My father’s affectionate stories about his foster-brother Otto did so too and their impact was enhanced by our proximity to Westerbork. We lived in a neighboring town, where my father was the burgomaster. During the 1960s we visited the site of the transit camp on a few occasions, at a time when some of the baracks had been demolished, while others were still standing.

My father considered tearing down the baracks a terrible mistake. This very spot, with its buildings full of memories, should be handled with extreme care and should be preserved. Many thousands of Dutchmen, subsequently killed in Nazi concentration camps, had spent their last days on Dutch soil here. It was important to their descendants to remember them at this very location, with the camp as little changed as possible. My father emphasized that to save such an important location a collective effort was required: “You need to form a group, constantly write letters of protest to point out how important this site is. And you need to involve the media, radio, television.” I was just twelve years old and was disappointed at my father’s inability to protect such an important site on his own. Yet some years later descendants of deportees formed a group that put pressure on the authorities. As a result the Westerbork Memorial museum was founded. It opened in 1983, but by this time almost all the baracks had been sold off or demolished.

Commemoration of the liberation of former transit camp Westerbork, (1985)

By 2008 my father was in his eighties and lived in a care home. I visited him every week and for many hours he told me stories from the time he was young. The stories often focused on his foster-brother Otto. I asked him: “Why did I never meet Otje when he came to the Netherlands?” My father answered that Otto rarely traveled. It was traumatic for him, as he had lost his mother and his father, both times after a voyage. Together with my father I called Otto on his birthday in February 2008. I was struck by the similarity in their tone of voice and idiom. My father advised me to contact his sister, who had kept in close contact with Otto. By this time I had decided to go to the U.S. to meet Otto. During my stay in Boulder I showed him numerous photographs from my father’s archive. Otto very enthusiastically introduced me to his friends and acquaintances when we met them on the street or in shops: “This is my foster-niece from Holland!”

Signs of Life

During her months at Westerbork, Hilde Verdoner wrote dozens of letters to her husband. The sense of Nazi terror is omnipresent in the letters, yet life in Westerbork was remarkably mundane and at the same time interpuncted by the dreaded weekly transports to the east. Hilde’s letters present a very intimate description of her experience, her fears, hopes, and worries. The correspondence is an important source, often used in publications about life in Westerbork. Decades later, her daughters Yoka and Fransje translated and edited her correspondence, together with a few of Gerrit’s letters, written a few years later. The resulting book, entitled Signs of Life: The Letters of Hilde Verdoner-Sluizer from Nazi Transit Camp Westerbork, 1942-1944, was published in January 1990.

Shortly before my trip to Boulder, my aunt Nel had told about Signs of Life, and I wondered why it had not been published in Dutch. Hilde’s children had donated the original letters to the Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies (niod) in Amsterdam. I went to the niod to read the letters and was so deeply impressed that I decided to do my utmost to get them published in the Netherlands. In the following months I visited Yoka, Fransje, as well as Otto, to sound out whether they would agree to the plan. Yoka and I prepared the publication together. The well-known Dutch historian Coen Hilbrink, a specialist in the history of Dutch World War Two resistance, provided an introduction. The book also includes a heartfelt letter written by Otto to his foster-mother Mia. Levenstekens was published in 2011 by Amsterdam publishing house Boom. Both Yoka and Fransje, together with one of her daughters and a granddaughter, attended the presentation at the Jewish Historical Museum in Amsterdam. Otto was not present in person, but was able to speak to many members of his foster family during the closing dinner via a videolink.

The children of Hilde and Gerrit kept in touch with the families that saved them. Nevertheless the war experience marked their lifes. Fransje married Robert Kan, who had fled with his family by ship when the Germans invaded the Netherlands. He often recounted their flight, and also told me about it when we met in 2009. While Otto did not visit the Netherlands often, his sister Yoka Verdoner regularly returns to the country where she was born and always includes visits to the daughter and grandchildren of Roosje Rijnders in her trips. In 2012 she asked me to accompany her to Weesp, in search of her father’s bicycle factory De Magneet. Yoka and I asked elderly passers-by whether they remembered the bicycle factory. Some of the people we spoke to replied that not Verdoner, but the co-director had been the real owner of the factory. They suggested that the co-director had unjustly been accused of collaboration with the German occupiers. After a few more street interviews, we returned to Amsterdam by car in silence.

Otto sitting on the lap of Nel Hopperus Buma, front left in the cart, pulled by Wietwim Hopperus Buma

Wedding

In 2019 Otto’s son David invited me to his wedding in Boulder, as the representative of the foster family of his father’s early years. The wedding guests, including almost all descendants of Hilde and Gerrit Verdoner, were staying in two adjacent hotels and had breakfast together. To an outsider, it may have looked like a perfectly normal group of happy American wedding guests, like so many other regular families in America. But the oldest three of the wedding guests also speak another languague. With Otto’s sisters Fransje and Joke—called Yoka in the U.S., for ‘obvious reasons’— I am able to speak Dutch. But the second generation has not retained the Dutch language and their children hardly know a single word of what used to be the common tongue of the Verdoner family. In my speech I explained my relation to the Verdoner family. The audience was very quiet during the speech. Afterwards many family members came up to me to ask questions and they were eager to hear more. Some knew about their fraught family history, but very few were comfortable talking about it. Family history can be bittersweet. But it also connects people.

About the author

Eline Hopperus Buma studied History of Art at the University of Amsterdam. She worked as a Senior Purser for KLM Royal Dutch Airlines. As a free lance journalist she published several articles on music, history, and art history and contributed to a book on Castle Groeneveld in Baarn. In 2011 she facilitated the publication of the Dutch version of Signs of Life, containing the letters from Hilde Verdoner who was murdered in Auschwitz.

The Dutch National Archives commissioned historian Jaap Jacobs to produce a series of 24 blogposts, 12 written by himself and 12 by co-authors, on the 400 year relationship between the Netherlands and the United States. Click here for the other parts.