Designed in 1957 and opened to the public on St. Patrick’s Day 1964, John Johansen’s US Embassy in Dublin was the last of the midcentury modern embassies to be constructed under the State Department’s modernist initiative — and it was almost never built.

By the early 1960’s, the embassy program had come under increasing political pressure, with Representative Wayne L. Hays (a Democrat from Ohio) and Senator John J. Rooney (a Democrat from Brooklyn) charging that the program was too expensive and produced buildings that were difficult to secure, inappropriate, and ugly. So great was the mounting pressure to end the program that President Kennedy personally intervened, taking executive action to move forward with the construction. In a letter to Hays in 1961, Kennedy wrote: “…while I agree that the design will not please all tastes, the delay and expense involved in redesigning the building indicate that we should go ahead with the present design.”

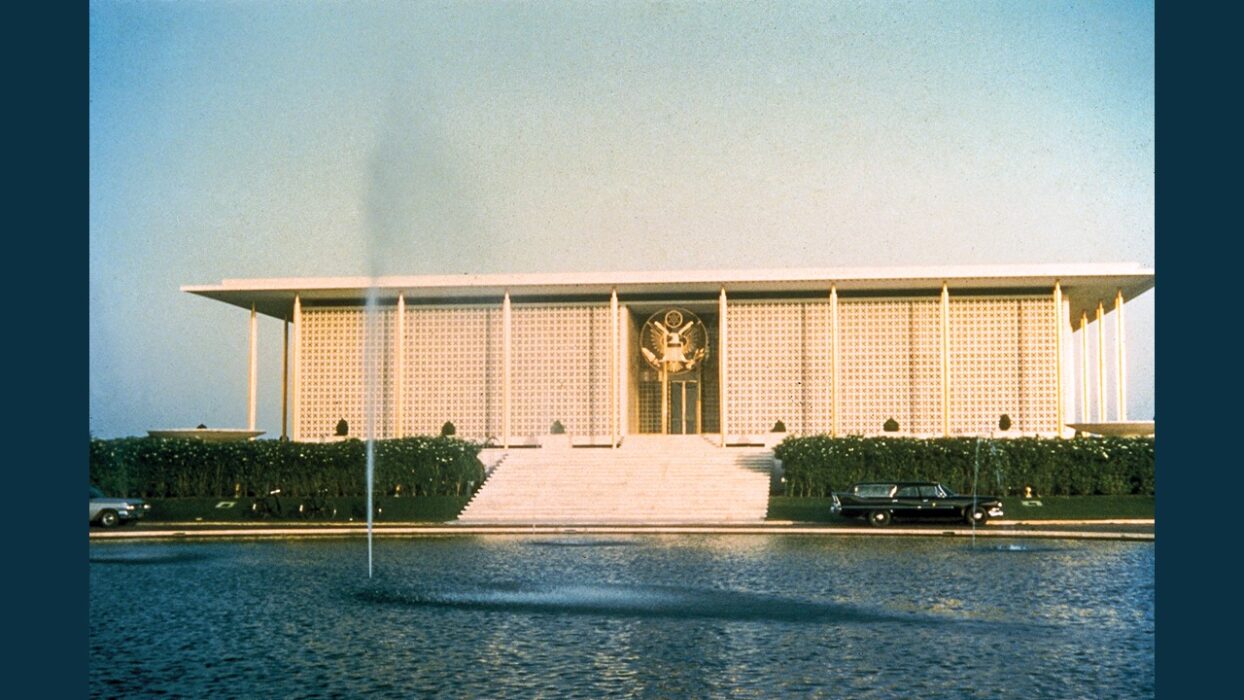

Johansen’s precast structural concrete elements in the process of installation

In this context, Johansen believed that he had been selected to design the Dublin embassy because of his reputation as a classicist, and attributed the President’s advocacy for his design to that reputation and to the friendship he had shared with Kennedy when they were students together at Choate and Harvard. Opening a new US Embassy in Dublin held a special significance for the first Catholic president of Irish descent. As a fellow Irish American and friend of Kennedy’s, Johansen likely struck the president as an ideal architect for the job.

As Architectural Forum noted in 1958, Johansen was confronted with three design challenges with the site of the new US Embassy in Dublin: “First, a problem in diplomacy—how to design a modern embassy that would have some reference to local traditions ; second, a problem in site planning—how to design a building that would look right on a pie-shaped corner lot ; and third, a problem in monumentality—how to give his building the kind of ruggedness that suggests permanence.”

Johansen’s final design confronts these problems with a building that marries modernism to the traditional, residential scale of its neighborhood while also marrying ancient Irish traditions to the modernist idiom, all in a structure that is technologically pioneering. The site of the building, at the intersection of Pembroke Road and Elgin Road in Ballsbridge, is on one of the oldest estates in Dublin. As in London, where Saarinen’s design for the US Embassy on Grosvenor Square was subject to the approval of the Duke of Westminster, who owned the land, in Dublin, Johansen’s design would be subject to the approval of estate authorities. The estate authorities in Ballsbridge were more open to modernism than other Dublin estates, but the sleek, International Style glass and steel buildings which had characterized the earliest embassies built under the program would not find approval here.

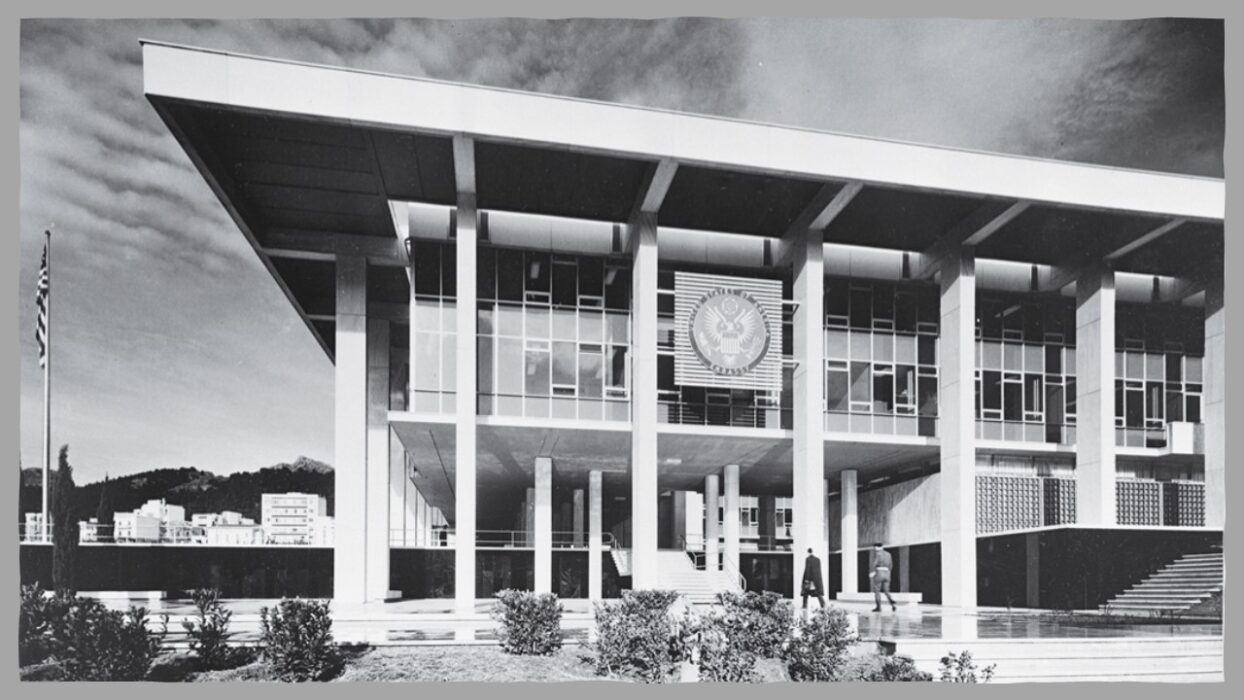

The main entrance, with its Johansen-designed Great Seal of the US

Consequently, Johansen’s design would have to exemplify the State Department’s emphasis on sympathetic design that exhibited American modernism while also incorporating local traditions. To achieve this, Johansen consulted with the Irish architect Michael Scott and arrived at a design for a round building that evoked the ancient Irish round towers and forts of the 9th to 11th centuries. The round building proved an ideal form for the irregular, triangular site in Ballsbridge.

The architectural precedents which Johansen drew upon were, at their heart, defensive structures, and the embassy, with its round tower and moat, represents the most defensive of the State Department’s deliberately non-defensive building projects. It is as much a signal of the end of the modernist embassy program as it is a harbinger of the era of defensive architecture which was soon to come.

The central rotunda shortly after the embassy opened in 1964

Johansen described the layout as Celtic-Christian in origin, and held that the building’s round configuration was a symbol of openness and the democratic ideal of not turning its back on its neighbors. As Johansen wrote: “The embassy building was the result of exhaustive studies on my part. The final version was accepted as an effective solution to difficult program and site problems, a mannerist, monumental, yet lively building, symbolizing government.”

Critics in the American and Irish press responded favorably to Johansen’s design. Architectural Forum hailed the building for bringing diplomacy and architecture together, and for the ways in which Johansen’s design looked past the prevalent Georgian influence in Dublin and found inspiration in more ancient, genuinely Irish precedents. The Irish Times echoed the sentiment, praising the embassy for its modernity and for its incorporation of traditional Irish designs. Mild criticism came from Dublin’s Georgian Society, which commented that the modern building may look out of place, but An Taisce (the National Trust for Ireland) awarded the building its premier award in 1969.

Today, the building holds local landmark status, and has influenced subsequent designs by other architects (for example, the British embassy in Madrid). The Biden administration announced in December its intention to purchase the former Jury’s Hotel and build a new US embassy on the site.

David B. Peterson is CEO of Onera Group, Inc. and Executive Director of the Onera Foundation, a private foundation dedicated to supporting historic preservation. Mr. Peterson is Board Chair of the Harlem Academy school, an independent school offering students a leading education regardless of economic circumstance. He serves on the Advisory Council of the Glass House, a National Trust Historic site. He holds a BA from Dartmouth College, an MBA from NYU, and a MS in Historic Preservation from the Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation. Click here to order ‘US Embassies of the Cold War’.

David B. Peterson is CEO of Onera Group, Inc. and Executive Director of the Onera Foundation, a private foundation dedicated to supporting historic preservation. Mr. Peterson is Board Chair of the Harlem Academy school, an independent school offering students a leading education regardless of economic circumstance. He serves on the Advisory Council of the Glass House, a National Trust Historic site. He holds a BA from Dartmouth College, an MBA from NYU, and a MS in Historic Preservation from the Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation. Click here to order ‘US Embassies of the Cold War’.