On March 3, 1945, Allied forces undertook an aerial bombardment of the Nazi-occupied Hague. The bombs missed their strategic military targets, landing instead in the historic heart of the city. The sophisticated Hôtel Paulez, which had stood at the intersection of Lange Voorhout and Korte Voorhout since the 1880s, was completely destroyed in the bombing.

Following the end of the war, the Dutch government considered a range of uses for the site of the former hotel. Plans for the redevelopment of the area had been ongoing since before World War II, and the US Government had been seeking to build a new embassy in The Hague since the early 1930’s. Following Nazi occupation of the Netherlands and the close alliance of the United States with the Dutch government-in-exile during World War II, the project to build a new US Embassy in The Hague became a central focus of Marshall Plan redevelopment in that city. Through a complex process of negotiation with the city’s planning authorities and multiple false starts, the US government purchased the land at the corner of Lange Voorhout and Korte Voorhout in August of 1951.

A series of political shifts resulted in major changes to the design of the new embassy. At the start of the postwar embassy program, the modernist architect Leland King was the leader of the US Foreign Buildings Office. He favored the International Style and was responsible for hiring Harrison & Abramovitz to design the first embassies in Rio de Janeiro and Havana. King awarded the commissions for the design of the new embassies in Stockholm, Oslo, Copenhagen, and The Hague to Rapson & Van der Meulen. In 1951, the firm designed a glass-façaded, International Style embassy complex for The Hague which consisted of a two-story tower raised above a recessed lobby on the ground floor.

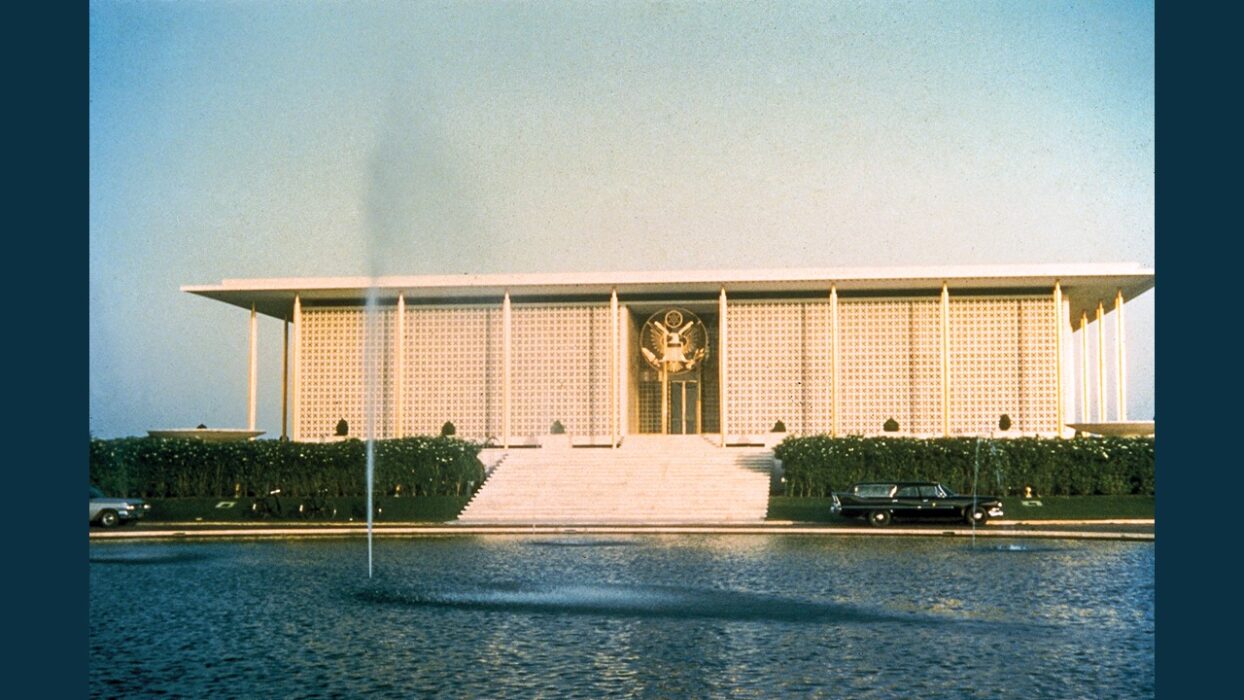

The main facade of the embassy along Lange Voorhout

Conservative opposition to the modern embassy designs in the US congress resulted in a dramatic shift in the program. Leland King was fired from his leadership of FBO in 1953. Nelson Kenworthy, who had led the internal investigation of the FBO, was appointed King’s successor. Under Kenworthy, the embassy program shifted to a more contextual design approach. The design of new diplomatic buildings was now overseen by the Architectural Advisory Committee, which officially favored neither modernism nor traditionalism, but whose mission was to “…give serious study to local conditions of climate and site, to understand and sympathize with local customs and people, and to grasp the historical meaning of the particular environment in which the new building must be set.” Diplomatic architecture would not be “…dictated by obsolete or sterile formulae or clichés, be they old or new.”

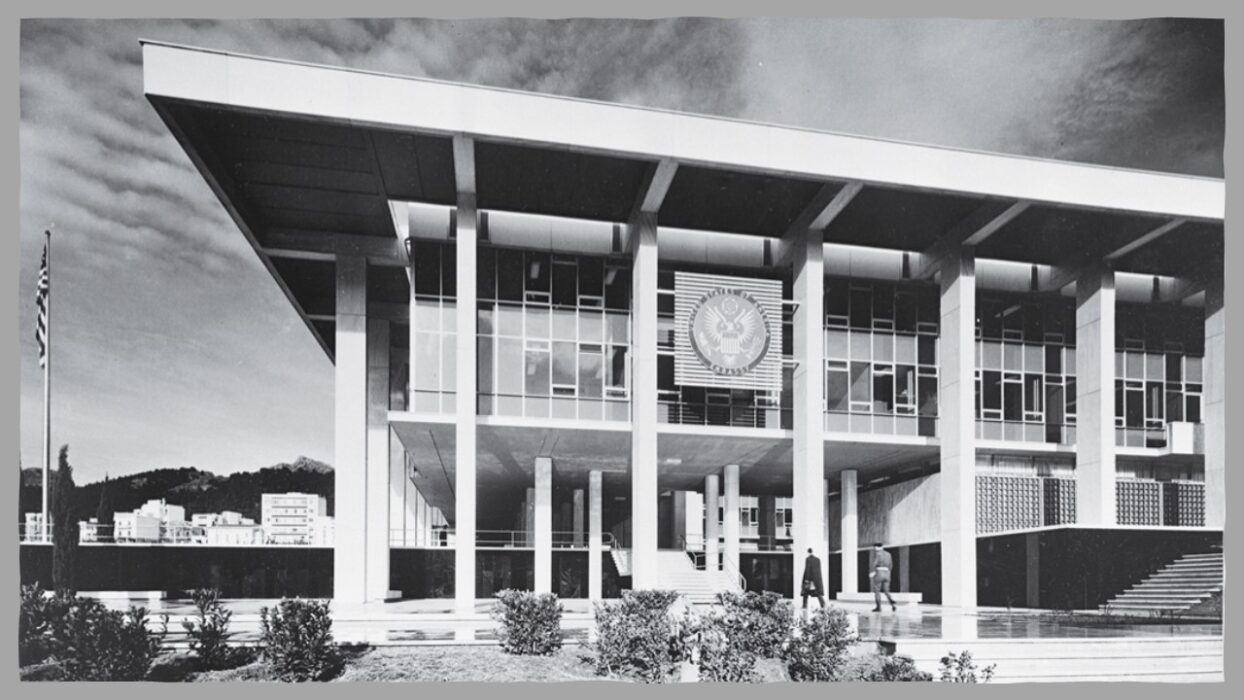

Marcel Breuer was among the architects identified by the new AAC as suitable for the embassy program. Breuer had been the talented protégé of Walter Gropius (founder of the Bauhaus and the architect of the new US Embassy in Athens, opened in 1961) and became one of the most influential architects and designers of his generation — gaining fame for such buildings as the UNESCO Headquarters in Paris (completed in 1958) and the former Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City.

Breuer visiting the embassy (1967)

Describing his approach to the AAC’s commitment to sympathetic and contextual design, Breuer said:

“… there is no need to compromise; a modern design, if good, will be appropriate. For example, the buildings bounding St. Mark’s Plaza date from several periods, but what is important there is the over-all character and unity of the space. Here, in The Hague, small scale is important, and so is the dignity of the building — the creation of a proper presence. A steel and glass building would strike a jarring, aggressive note— masonry would seem to be much more at home in this situation.”

Breuer’s resulting embassy building has three principal façades, one facing Lange Voorhout, another facing Korte Voorhout, and an auditorium building in the rear of the complex. The external walls are composed of load-bearing, reinforced concrete clad with light gray panels of German Muschel limestone. The embassy was to be built in an urban context characterized almost exclusively by high Baroque architecture, but Breuer insisted that the building’s limestone-clad masonry harmonized the building to its classical context without being sterile or imitative.

Auditorium

The Dutch press was initially skeptical that the modern design would succeed in harmonizing with its surroundings, but the building is now hailed as a masterpiece of the Netherlands’ Wederopbouw, or “post-war building era.” Decommissioned as an embassy and officially handed over to the Netherlands in March of 2018, the building now houses West Den Hague, a contemporary art museum. The United States Embassy in the Netherlands was moved to a highly secure, more remote location in The Hague in January of 2018.

David B. Peterson is CEO of Onera Group, Inc. and Executive Director of the Onera Foundation, a private foundation dedicated to supporting historic preservation. Mr. Peterson is Board Chair of the Harlem Academy school, an independent school offering students a leading education regardless of economic circumstance. He serves on the Advisory Council of the Glass House, a National Trust Historic site. He holds a BA from Dartmouth College, an MBA from NYU, and a MS in Historic Preservation from the Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation. Click here to order ‘US Embassies of the Cold War’.

David B. Peterson is CEO of Onera Group, Inc. and Executive Director of the Onera Foundation, a private foundation dedicated to supporting historic preservation. Mr. Peterson is Board Chair of the Harlem Academy school, an independent school offering students a leading education regardless of economic circumstance. He serves on the Advisory Council of the Glass House, a National Trust Historic site. He holds a BA from Dartmouth College, an MBA from NYU, and a MS in Historic Preservation from the Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation. Click here to order ‘US Embassies of the Cold War’.