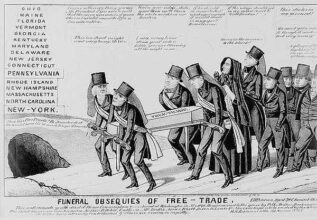

By conventional wisdom, the United States’ first serious threat of secession did not strike until the Nullification Crisis of 1832-1833, when South Carolina menaced disunion over what many Southerners described as the federal government’s “Tariff of Abominations.” They viewed the tariff as both oppressive to the Southern economy of staple export crops––and flatly unconstitutional.

Cartoon Nullification Crisis 1832-33

In fact, the first major disunionist threat took place more than a half century earlier. In October of 1774, at the outset of the American Revolution, South Carolina became so enraged at the prospect of a mandate to cease all rice and indigo exports that the state’s delegates walked out of the First Continental Congress in protest, refusing to return until their demand for justice was delivered by the central body.

This episode of American disunion, recounted in my book Disunion Among Ourselves: The Perilous Politics of the American Revolution, is a stark reminder that the founding of a single nation was hardly the easy marriage of thirteen homogeneous, liberty-loving states so often depicted in the pages of history.

In fact, it is almost certain that the founders of the United States would have split the thirteen states into two or three confederations at the end of the Revolutionary War––Northern and Southern, or Northern, Middle, and Southern––if not for one overwhelming geopolitical fact. Those separate confederations, the founders were sure, would rapidly fall into civil wars.

In the book, I liken the Union of thirteen dissimilar, combative states in the 1770s and 1780s to a “shotgun wedding.” That is to say, if the New England or Southern states had chosen to secede from the Union of thirteen, civil wars would have broken out. Americans would have killed Americans on the battlefield. For this reason–the prevention of civil wars between regional confederations–the founders reluctantly bound themselves into one American government during and after the War of Independence.

In the book, I liken the Union of thirteen dissimilar, combative states in the 1770s and 1780s to a “shotgun wedding.” That is to say, if the New England or Southern states had chosen to secede from the Union of thirteen, civil wars would have broken out. Americans would have killed Americans on the battlefield. For this reason–the prevention of civil wars between regional confederations–the founders reluctantly bound themselves into one American government during and after the War of Independence.

The founders’ deep-seated fears of disunion leading to civil wars helps to explain why they “compromised” so often during the nine years of the American Revolution. They took the high road because the only alternative to compromise was a political break-up of the fledgling United States, one that would inevitably lead to civil wars over federal debt, commerce, and, most of all, land.

A case in point of this dynamic of secession threats engendering either disunion or compromise is the short-lived secession of South Carolina from the First Continental Congress in the fall of 1774. Every other colony in attendance of the Congress chose to adhere to a staged full-scale embargo of all imports and exports to Great Britain in the event that Parliament did not rescind the hated Coercive Acts that that were then oppressing Massachusetts government and obliterating commerce into Boston Harbor.

South Carolina refused, arguing that a total trade embargo was unfair and unequal to its home colony’s staple crops of indigo and rice. The delegates from that colony claimed that the non-exportation clause as written overwhelmingly favored “the Northern Colonies” due to a combination of existing legal patterns of commerce, ship ownership, trade relationships, and those colonies’ expertise in smuggling. As one of the South Carolina delegates described, “he could never consent to our becoming dupes to the people of the North.”

In this state of mind, the South Carolinians demanded a revision of the non-exportation clause, exempting rice and indigo. When other delegates pushed back, the planters stiffened, declaring not only that they would not sign the embargo without this exemption but they would take their leave and return to South Carolina. To evidence their sincerity, they did in fact stage a walk-out. Effectively, South Carolina nullified the non-exportation ruling and seceded from the Congress for several days.

As explained by historian Edmund Cody Burnett in The Continental Congress, the American Union broke apart that mid-October of 1774, salvaged only by compromise. The South Carolinians, Cody writes, “laid down an ultimatum that, unless South Carolina staples, rice and indigo, should be exempted from the non-exportation provision, they would not sign the Association; and those delegates did in fact withdraw from Congress for the time being. . . . Thereupon, to prevent the break-up of the union, a compromise was effected whereby the South Carolinians yielded their contention with regard to indigo on condition that an exception be made of rice.”

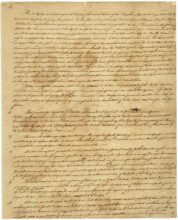

The Continental Association, 1774

In this way, thus, the delegates to Congress enacted their first commercial legislation, the Continental Association. They did not know it at the time, but in 1774 they were establishing a lasting operating principle of American government that would not be fully abandoned until the Civil War.

That principle was extortion by threats of nullification and secession. In the early years, like later years, whenever genuine disunion reared its head, Union-saving compromise became the only reliable remedy to rescue the Union from dissolution and, as its natural consequence, the outbreak of civil wars among the states.

Eli Merritt is a political historian at Vanderbilt University who specializes in the founding era of the United States, the ethics of democracy, and the intersection of demagogues and democracy. He is the author of ‘Disunion Among Ourselves: The Perilous Politics of the American Revolution’. He is also the editor of ‘The Curse of Demagogues: Lessons Learned from the Presidency of Donald J. Trump’ and ‘How to Save Democracy: Inspiration and Advice from 95 World Leaders‘. His articles have appeared in the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, and Chicago Tribune, among other outlets, and he writes American Commonwealth, a Substack newsletter that explores the origins of the United States’ political discontents and solutions to them. Sign up for American Commonwealth.