The first direct shipment of enslaved Africans arrived in New Amsterdam in 1655. The voyage of the White Horse came in the wake of significant changes in the Dutch Atlantic. In this blog, American historian Dennis Maika outlines how family and business connections shaped the development of a slave-trading center in Manhattan.

New Amsterdam’s residents would have immediately noticed something different about the arrival of the Witte Paert (White Horse) in the early summer of 1655. The stench of human excrement and illness emanating from the newly arrived “scheepgen,” (small ship) left little doubt that a slaver had arrived after a long voyage. A vessel devoted exclusively to the slave trade had not been seen before in Manhattan because in the past only small numbers of captives arrived irregularly aboard privateers and were sold as “prizes.” The Dutch West India Company had thus far never sent enslaved Africans to New Netherland, in spite of their hints and unfulfilled promises. The arrival of the first vessel to sail from West Central Africa was unique in another way: it was organized and funded not by the West India Company but exclusively by Dutch private investors.

West India Company warehouse in Amsterdam (ca. 1693)

Trafficking Humans

Today we wonder how businessmen—commercial entrepreneurs—could make a decision to traffic in human beings, but we must recognize that long ago, “commodifying” human beings was an underlying assumption in Atlantic World commerce. The slave trade between Africa and the Western Hemisphere was introduced by the Spanish and Portuguese in the early sixteenth century, and by the mid seventeenth century free individuals in the Dutch Republic, Western Africa, New Amsterdam and the Chesapeake easily and automatically placed financial value on enslaved Africans. As we focus on how and why such individual decisions were made by investors in New Netherland, we can see the factors that shaped slavery as it first developed in North America.

Dirck Pietersen was among dozens of seventeenth-century Amsterdam merchants willing to add human trafficking to their commercial portfolios after the West India Company’s Amsterdam Chamber opened the slave trade to private investors in the late 1640s. In November 1654, in partnership with Jan de Sweerts, he requested permission from the WIC’s Amsterdam Chamber to bring enslaved Africans directly to New Netherland. But such a venture was particularly risky—the historical uncertainty of New Amsterdam’s slave market and the many hazards and captive fatalities that would accompany an exceptionally long voyage made any profit highly speculative. Why then did these two partners decide to do what had never been tried before?

Extract from the register of resolutions of the West India Company, granting permission to the Witte Paert for their journey.

At this particular moment in time, several important developments in the Atlantic world improved the partners’ chances for success. First, the final surrender of Dutch Brazil in early 1654 not only disrupted the sugar trade but also the lucrative West African slave trade that supported it. Jan De Sweerts and his brothers Jacob and Paulus had recently left Brazil, returning to Amsterdam where they hoped to reconfigure their family’s business. Actively involved in the Brazil-West African trade, De Sweerts saw an opportunity to divert African captives previously intended for the sugar plantations of Pernambuco or Paramaribo to the West Indies and New Netherland. He hired Meijndert Lourensz Swart, a seasoned skipper with experience navigating and trading in the Gulf of Guinea, to secure a cargo of West African captives and take them to New Amsterdam for sale. That New Amsterdam could now be considered a viable slave market was due to the end of the First Anglo-Dutch War, which occurred only months after Brazil’s fall. With significant commercial growth in the years before the war, New Amsterdam had begun to emerge as a regional and international entrepot due, in part, to the exchange of Dutch imports for Chesapeake tobacco. With personal experience and contacts in that market, Dirck Pietersen knew that Virginia and Maryland planters were eager to reinvigorate their trade through New Amsterdam. He was also well aware that Chesapeake planters had become more keenly interested in acquiring enslaved labor.

Map of “The Gold Coast of Guinea,” ca. 1670.

Merchant Families

Amsterdam and Rotterdam investors had begun to take commercial positions in Chesapeake tobacco in the 1640s as the English Civil War disrupted trade between England and Virginia. Amsterdam’s Verbrugge family was among these early investors, as was Simon Overzee from a prominent Rotterdam tobacco trading family. By December 1648, a pamphleteer reported that half of the twenty-four European vessels trading in the Chesapeake were Dutch. Oliver Cromwell’s Commonwealth tried to reduce this dependency by creating the first Navigation Act of 1651, restricting direct trade with the Dutch. But Chesapeake’s dependence on Dutch markets was so strong that Virginians looked for ways to maintain their connection through New Netherland. Director General Petrus Stuyvesant encouraged this new perspective and sent negotiators to Virginia to secure a provisional commercial treaty in 1653 intended as an “inducement for extensive trade and sale of merchandize.”

Family connections helped establish the critical link between New Amsterdam and the Chesapeake tobacco trade. The Verbrugges had become one of the leading Amsterdam investment families in New Amsterdam, represented in Manhattan by their resident agent Govert Loockermans. Another critical connection was made by Pieter Varlet, a prosperous silk and cloth merchant and former West India Company Director, and his brothers Caspar and Daniel. By the early 1650s, the Varlets established both residency and family connections to facilitate their Chesapeake trade. In 1651, Caspar moved his entire family to New Amsterdam where his son Nicolaes joined the tobacco trade with his new brother-in-law, Augustine Herrman who with some justification, later claimed to be the “first beginner of Virginia tobacco trade.” Nicolaes’ sister Anna married George Hack, a prominent Virginia tobacco planter and trader.

It was Anna Hack who was among the first merchants to bring enslaved Africans from New Amsterdam to the Chesapeake. In 1652, she purchased eight captives from the St. Anthonij, a Spanish “prize” taken by a French privateer with a Dutch captain. No doubt she and her fellow Virginia growers happily greeted the news that enslaved Africans could be purchased in New Amsterdam. The appeal was not only for labor; as a result of a 1652 agreement between the Cromwellian government in England and Virginia, anyone responsible for bringing people into Virginia would receive a fifty-acre head right per individual.

From his business connections in the Chesapeake, Dirck Pietersen was well aware of these new developments. Most recently, Pietersen sold his first vessel named the Witte Paert to Simon Overzee who renamed it the Virginia Merchant. Using a familiar name with his newly purchased ship would certainly remind potential buyers of their previous experience. Thus, although the partners promised the Amsterdam Chamber directors that they were supporting Company goals of building New Netherland’s population and agriculture, their real mission was to service eager Chesapeake buyers.

The White Horse

The Witte Paert arrived as the early summer trading season in Manhattan was underway, joining at least six other ocean-going vessels in the harbor, including the city of Amsterdam’s warship, the Waegh, awaiting its upcoming mission against New Sweden. These were joined by many smaller boats, some bringing Chesapeake tobacco for export. Among these was a vessel used by Edmund Scarborough, a prominent Virginia planter known to Overzee, the Varlets, Herrman, and Loockermans. Whether by coincidence or intention, Scarborough was in New Amsterdam at the precise time the Witte Paert arrived. When skipper Meyndert Lourensz Swart held an auction for his cargo, Scarborough was the largest purchaser. We have no record of the precise number of captives he purchased, but from forty-one headrights he filed in Virginia by the end of the year (guaranteeing him some 3500 acres of land in Virginia) and the fourteen headrights acquired by his friends and family, it is safe to assume that he purchased at least 55 Witte Paert captives, some of whom he resold in Virginia and Maryland.

Peter Stuyvesant, Director-General of New Netherland

Stuyvesant was perhaps surprised to find the Witte Paert in the upper bay. He recently returned from a trip to Barbados and Curaçao exploring new commercial opportunities and only then received Directors’ notice of the Witte Paert permit. The resolution said nothing about what to do if the enslaved were to be taken away from Manhattan, so Stuyvesant, unwilling to interfere with auction sales already made, granted Scarborough special permission to take captives to Virginia. The only stipulation was that Scarborough promise, under hefty bail, that he would not enter the South Bay or the South River and inform the Swedes of Stuyvesant’s pending invasion. The Company was clear, however, that all proper duties and imposts be collected. Stuyvesant immediately obliged, ordering a ten percent duty be paid on slaves exported from New Netherland.

We don’t know whether or not Pietersen and de Sweerts were financially successful in their slave-trading venture. Accurate accounting of all transactions was the responsibility of the skipper, Meyndert Lourensz Swart, who was killed in a confrontation with local Munsee natives on Staten Island and whose papers have disappeared. New Amsterdam court records show that his successor was still trying to collect on promised payments in October of that same year. Notarial records in Amsterdam reveal that as late as 1659, Pietersen and De Sweerts’ son had still not been fully compensated by Scarborough, Herrmans, and several other purchasers. Although such payment delays were common in seventeenth-century Atlantic commerce, it appears as if any financial benefits resulting from the voyage were not encouraging enough to have the partners try again.

Profit and Pain

Financial records are of little help in identifying the ledger of atrocities experienced by the Witte Paert captives. We know something about the pain and suffering experienced by only two of them. We’ve learned that an unnamed woman was forcibly intoxicated by the ship’s captain to mask her serious illness from potential buyers. After the auction, she was carried through the streets, screaming as she realized her condition, to the house of Nicolaes Boot, where she died three hours later. We only know of her story because Boot, her purchaser, sued the captain for fraud and refused to pay. We also know about Antonio, a captive eventually sold to Simon Overzee. Antonio fiercely resisted his enslavement by refusing to work on Overzee’s new plantation in Maryland and by running away. In the course of “correcting” Antonio’s behavior, Overzee had him beaten, hot lard poured into his wounds, then suspended on a ladder where he soon died. We only know Antonio’s story because one of Overzee’s political enemies had him prosecuted for manslaughter. Overzee was acquitted.

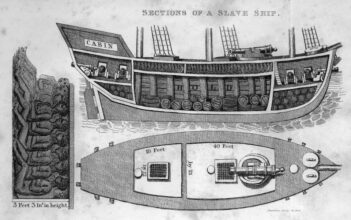

Sections of a slave ship

It is obvious from the Witte Paert’s voyage that calculating profit based on commodifying human beings was the driving force behind the early slave trade. Any calculation of risk by men like Dirck Pietersen, and Jan de Sweerts could not have been made without assigning monetary value to human life. It is also clear that personal networks were essential in building reliable markets and exchanges. But we also learn that the slave trade, even if privately funded, could count on institutional support from Company officials and local magistrates to facilitate sales and protect investment.

The Witte Paert’s example demonstrated to those considering future slave trading that a dependable supply of captives and an expanding network of purchasers were essential components for financial success. Within five years, subsequent attempts by the West India Company depended on Curacao as a slave depot from which to bring the captives to New Amsterdam, whose position as a regional hub now added the South (Delaware) River colony of New Amstel to its network. The culminating effort of this new strategy was in the Company-sponsored 1664 voyage of the Gideon, that would travel from Amsterdam, to West Africa, to Curacao, then finally to New Amsterdam with 291 enslaved captives. Although the English invasion fleet that arrived at the same time as the Gideon temporarily altered the slaving trajectory, New York would ultimately become a slave-trading center in the eighteenth century.

Dennis J. Maika (PhD New York University, 1995) is Senior Historian at the New Netherland Institute. Last year The Dutch National Archives commissioned historian Jaap Jacobs to produce a series of 24 blogposts, 12 written by himself and 12 by co-authors, on the 400 year relationship between the Netherlands and the United States. Click here for the other parts.