Kees Ribbens is a big comic book fan. He has a large collection of comic books, many of them about World War II and so I interviewed him about his involvement with Franklin – A Dutch Liberation Story. He is also a senior researcher at the NIOD, the Netherlands Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies and one of the organizers of the exhibition ‘Black Liberators’, about the African American soldiers in the US army in the Second World War.

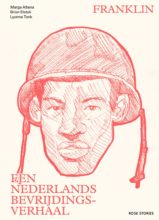

Franklin: A Dutch Liberation Story

It was Kees Ribbens’ and Mieke Kirkels’ idea to create a graphic novel as a way of telling the story of the Black Liberators, the African American soldiers who helped liberate the Netherlands at the end of World War II. Black Dutch artist Brian Elstak was asked to draw it. The result is Franklin – A Dutch Liberation Story. You can read my interview with Brian Elstak here.

Given his interest in popular culture, Ribbens himself has a substantial number of comic books published in various western countries. But actually very few of them depict black soldiers in World War II. Throughout the 1950s, ‘60s and ’70s an incredible amount of cheap black-and-white comics about World War II were produced. They could hardly be called nuanced depictions of history, and so the absence of African American soldiers is not very surprising.

Sergent O’Brien, by Jean Pape

The comic Sergent O’Brien (written in France in the 50s) shows an African American soldier, but he is portrayed as part of a white squad of soldiers and as carrying a weapon. The illustrator completely disregarded the fact that the US army remained strictly segregated until 1948, and that African American soldiers were rarely allowed in combat roles in Western Europe, during World War II.

Only more recently have comic books started to pay more attention to soldiers of color. For instance, recent French comics now often feature soldiers from the French colonies in both World Wars. Ribbens explains: “Comic books are not the most progressive of literary genres. They often follow where film and novels have gone before. They are more a reflection of movements in society than they are pioneers. Perhaps that is why it is only now that comics have started to incorporate minorities into their depictions of history.”

Commemoration 1955, Wageningen

Why have the Black Liberators have been absent so far from the Dutch collective memory of World War II and the liberation? Ribbens: “Historical collective memory tends to be somewhat one-sided and lacking in nuance. The liberators were Brits, Canadians and Americans. Most of them were white men and so they were all remembered as white men. Moreover, the Dutch have always focused on the liberation of the north and the west of the country in 1945. The liberation of the south by the Americans in 1944 is a less-known chapter. As a consequence, the African American soldiers, who made up some 10% of the American army that liberated the South, were left out of the picture.”

The graphic novel Franklin finally acknowledges the role that African American soldiers played in the liberation of the Netherlands. Our collective historical memory is becoming more diverse, more inclusive. This is due in part to changes in the Dutch population during the past decades.

Cemetery Margraten

Kees Ribbens explains how the NIOD became involved in the Black Liberators project. A few years ago, with the 65-year commemoration of the end of the war, a government grant to the NIOD helped to start research into the multicultural aspects of World War II. At the same time a project was initiated to study the history of the American cemetery at Margraten. This research revealed that the cemetery was constructed by African American soldiers, and a number of African American soldiers are buried there. This discovery represented a forgotten piece of history: the role African American soldiers played in the Netherlands during World War II. Mieke Kirkels has continued this line of research in recent years, revealing various stories of these African American soldiers and their descendants.