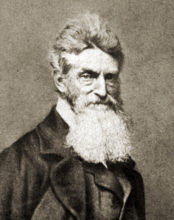

John Brown

John Brown, a white man, was a fierce opponent of slavery who saw the enslavement of black people as a sin against God. At an anti-slavery convention in Canada in 1858, he proposed the creation of a free state under a new set of laws called the ‘Provisional Constitution of the United States’, which would apply to anyone who joined his cause. Brown became Commander in Chief of the Provisional Army, which consisted of only twenty-two men, sixteen white and five black (four of them were born free, one was a freed slave). Extensive preparations followed. On October 16, 1859 he finally told his followers: “Men, get on your arms. We will proceed to the Ferry.”

Harpers Ferry, 1859

Smooth start

Strategically, the attack on Harpers Ferry made sense. To reach Maryland and disappear into the wildness of the Blue Ridge Mountains, you needed only to cross the bridge over the Potomac River. Also, the town was home to the United States Armory and Arsenal, where over a hundred thousand guns were stored. Surprisingly, the Armory was hardly guarded. Upon entering Harpers Ferry around 10.30p.m., they encountered just two watchmen: one on the bridge and one at the Armory. This might seem odd. But in the late nineteen hundreds, an organized attack on the US government by its own citizens on such a scale was simply unimaginable. Rumors of the raid even reached the Secretary of War, but he dismissed it as something not very likely to occur.

Bridge over the Potomac River

With the darkness providing cover, John Brown and his men easily took over. Within a couple hours they took 60 hostages (among them the great-grandnephew of George Washington) who were confined in the fire engine house, which later would become known as John Brown’s Fort.

Going down

But things quickly fell apart. At 1.30 p.m., a train arrived at the station which was held until daylight. The long stop-over stirred enough commotion on the train for Howard Shepherd, the station baggageman, to walk out to see what was happening. He was shot and killed by John Brown’s men as he approached the bridge. The first victim of the raid had fallen. He was a black man, a former slave, already free. John Starry, the town’s doctor, also became alarmed after noticing armed black men in the streets. He saddled his horse and warned the authorities. Soon the bells of a nearby church rang out to warn the town’s citizens. Meanwhile, the passengers on the train that had been allowed to continue its journey, told everyone at the next station that a massive slave revolt was underway in Harpers Ferry. So great was the fear in the South of an armed slave uprising, that the number of raiders got higher every time the incident was passed on.

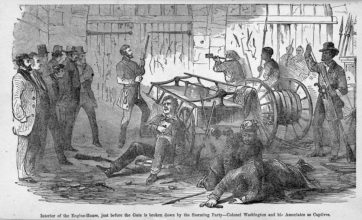

John Brown’s Fort

Killed, captured, questioned

While John Brown and his small group of men waited for the hundreds of slaves and other like-minded men who they expected to join the fight (but who never came), the townspeople, several militias and the U.S. Marines moved in. On October 18, Robert E. Lee, who would soon become the Commander of the Confederate States Army, quickly captured or killed most of the raiders and stormed the engine house where John Brown and the last of his men and their hostages were now trapped. Once they were in, the ordeal lasted no more than three minutes. Brown and his surviving followers were arrested.

During his questioning John Brown made clear that, although he failed, the story of his raid did not end there: “You may dispose of me very easily; I am nearly disposed of now; but this question is still to be settled – this Negro question I mean – the end of that is not yet.”

The capture of John Brown