By Briitta Mohney

The photography exhibit ‘One Steinway Place’ by Christopher Payne is on show until November 9th at the Temporary art space in Amsterdam Noord. Payne was trained as an architect and is now a successful photographer, focusing on America’s vanishing architecture and industrial landscape and more recently on the perseverance of craftsmanship and small-scale manufacturing. He talks to the John Adams Institute about the shift in his career and the inspiration behind this stunning body of work.

1. What sparked your interest in photography?

I was doing drawings of some industrial buildings as a summer job, slaving away for hours and a photographer came in and took pictures to complement my drawings as a way to round out the project. I remember seeing what he was able to do with the camera – elevate this boring structure into something that was like art. And I remember thinking, that’s incredible, he is creating something entirely new that doesn’t exist. It was those moments, more than my own tinkering with a camera, that slowly pushed me into photography.

2. What brings architecture and photography together?

Planning the photograph in your head is the same as making a sketch of a space as an architect. When I was starting out as a photographer, I would often make sketches of what I wanted to photograph. The composition of a photograph and a sketch is the same, just a different medium. My eye is still attuned to the built form and to spaces, but now it has been honed to a different discipline.

3. The “One Steinway Place” collection was a project that you envisioned for eight years after going on a tour at the Steinway factory in 2002. What made you go back?

During that tour in 2002 I was almost moved to tears. The scene of the wooden rims drying after they have been bent on massive presses is the shot that I thought about for eight years. What started out as just a plank of wood had the shape of a piano twenty minutes later. Being able to see the piano in this elemental form was so moving, because I knew instantly what it was. It’s a shape that we all know and love and seeing it in that incipient stage – I just didn’t expect it.

4. What story are you trying to tell with this collection of photographs?

What I’ve tried to show here is a different side of the piano. On one hand, these photographs look inside, under the lid into the method of assembly and the choreography of production. But its also a celebration of the built form and of craftsmanship, something I fear is becoming all too rare in the American workplace.The power of the piano making process is that most of the activity happens within the reach of the human hands. There is nothing romantic about it, it requires craftsmanship and skill and apprenticeship and they’ve been doing it the same way since the 19th century. This is a great example of how old-world craftsmanship can still flourish.

5. In your previous projects, you’ve focused on landscapes and buildings that are vanishing. Why the shift from that to this celebration of craftsmanship?

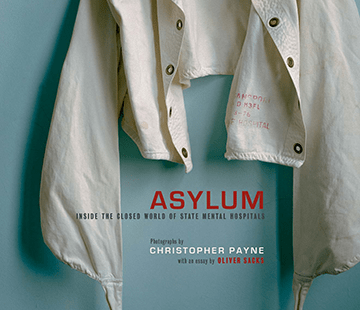

I’ve always had an appreciation of the built form and of assembly. The way I understand the environment is by taking it apart, by deconstructing it. This Steinway collection is a deconstruction of a whole into parts, whereas a previous project, Asylum: Inside the Closed World of State Mental Hospitals, was reconstruction of ruins, a reconstruction of the parts into a whole. By going to all these different hospitals around the country and taking photographs, the collection showed this model hospital system as it once was. The evolution of might seem like a jump but actually what fascinated me about the hospitals was that there was this manufacturing component that allowed the hospitals function. To keep themselves going, they put the patients to work. So as I was photographing things we associate with a mental hospitals, I was also photographing shoe shops, gardens, farms, slaughterhouses. This was a very self-contained community and the fact that they made their own clothing, shoes and food made me want to photograph something that is being made instead of photographing something that is gone.

I’ve always had an appreciation of the built form and of assembly. The way I understand the environment is by taking it apart, by deconstructing it. This Steinway collection is a deconstruction of a whole into parts, whereas a previous project, Asylum: Inside the Closed World of State Mental Hospitals, was reconstruction of ruins, a reconstruction of the parts into a whole. By going to all these different hospitals around the country and taking photographs, the collection showed this model hospital system as it once was. The evolution of might seem like a jump but actually what fascinated me about the hospitals was that there was this manufacturing component that allowed the hospitals function. To keep themselves going, they put the patients to work. So as I was photographing things we associate with a mental hospitals, I was also photographing shoe shops, gardens, farms, slaughterhouses. This was a very self-contained community and the fact that they made their own clothing, shoes and food made me want to photograph something that is being made instead of photographing something that is gone.

Christopher Payne is based in New York. A book based on ‘One Steinway Place’ will come out next year. Visit his website here and read more about the exhibit here.